The phrase ‘putting out to pasture’ springs to mind when writing this final chapter.

There are many examples of long-running series that are gradually diminishing in budget, scheduling, or resources at their disposal.

From a contemporary point of view, Doctor Who is a classic example. Upon returning from its Michael Grade imposed exile in 1986, the series running time was cut by 50%, and throughout its final four seasons, saw its lead actor replaced, its publicity reduced, and crucially, it was scheduled against the other titan of the soap opera world – Coronation Street – before disappearing quietly altogether.

There are some parallels with Whistle Test.

The first evidence of a significant budget cut was the ‘86 Whistle Test 87‘ edition – otherwise known traditionally as the ‘Pick of the Year’. This new year live special, couldn’t be more different from 12 months ago.

Suddenly, the postmodern ‘Comfy Area’ had disappeared. The black leather seating was replaced by what looked like a cheaper model, and the desk and the marbled background were now replaced by something that looked distinctly cobbled together from whatever backdrop, set dressings and Christmas decorations were knocking around. This suggested a budget that scrapped the barrel of even Whistle Test’s modest leanings.

Tellingly, the presenting team was stripped right back, with Mark Ellen and Andy Kershaw more than likely sober, but possibly disobeying strict orders from the producers to not touch a drop of alcohol until they were off the air at 3am. Yet, by midnight, they could be seen sipping freely at the BBC hospitality, while offering the links from the makeshift studio, which would slowly become more cluttered and chaotic as the evening progressed. Perhaps they both recognised the seemingly makeshift conditions they were broadcasting from?

Ro Newton presented a live concert from Kim Wilde at the Chippenham Goldiggers – complete with an introduction that included jugglers and fire-eaters, in a type of set-up not too dissimilar from a charity telethon. This was Newton’s penultimate appearance; she would not be seen on Whistle Test for another 12 months.

Elsewhere, David Hepworth presented a filmed special from Houston, documenting the preparations for Jean-Michel Jarre’s April 1986 concert – this and a special edition filmed in Japan (in April 1987) would be Hepworth’s final on-screen contributions to Whistle Test.

Sounds magazine was clearly not impressed. The financial well was running dry. For the first time, it was visible to the viewer.

It suggested leaner times ahead.

There is a sense of full circle for the series solely known as Whistle Test. This final run of 11 episodes, transmitted at the beginning of 1987, mirrored the first foray into a post ‘Old Grey’ world in early 1984. Both series ran from January – March, both were presented by two presenters, both had shorter than usual timeslots, and therefore generally featured one live studio act, and both had no title sequence to speak of.

So, let’s delve in.

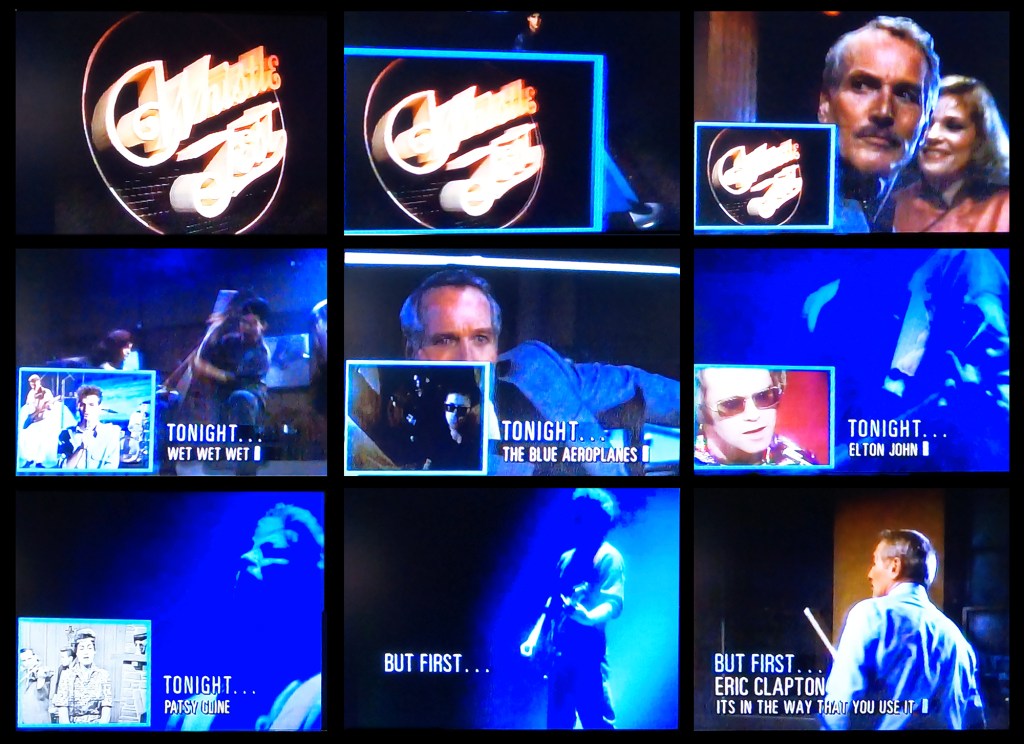

A new logo was commissioned for this series. The modern sans serif typeface was replaced by an (almost) Spencerian script style of lettering, positioned within a circular frame. It doesn’t speak of the 1980s, and perhaps feels more suited to advertising than music. Any connection to the essence of the show is unclear, and while the actual lettering is attractive, it doesn’t work as a logo, not due to any fault of the graphic designer, but because it is positioned within a show that has lost its visual identity.

The stage set included new circular hangings that framed the new polystyrene cut logo. The post-modernist classical facade was retained, although the Venetian blinds only appeared occasionally. The Comfy Area was now reduced to a single television monitor and some cheap-looking baggy leather sofas. The new logo featured within the graphic captions, although it was accompanied by the same sans-serif typeface as the previous series, and augmented by a flashing cursor.

It is a mish-mash of styles that doesn’t add up to a cohesive visual concept.

Perhaps the most disarming decision was to lose the title sequence and theme tune. Martin Foster’s filmed intro, which debuted during the live series of 1984, now feels like a million miles away. Across the three Whistle Test series that followed, the sequence was tinkered with, then replaced by a cheaper version, and now dispensed with altogether.

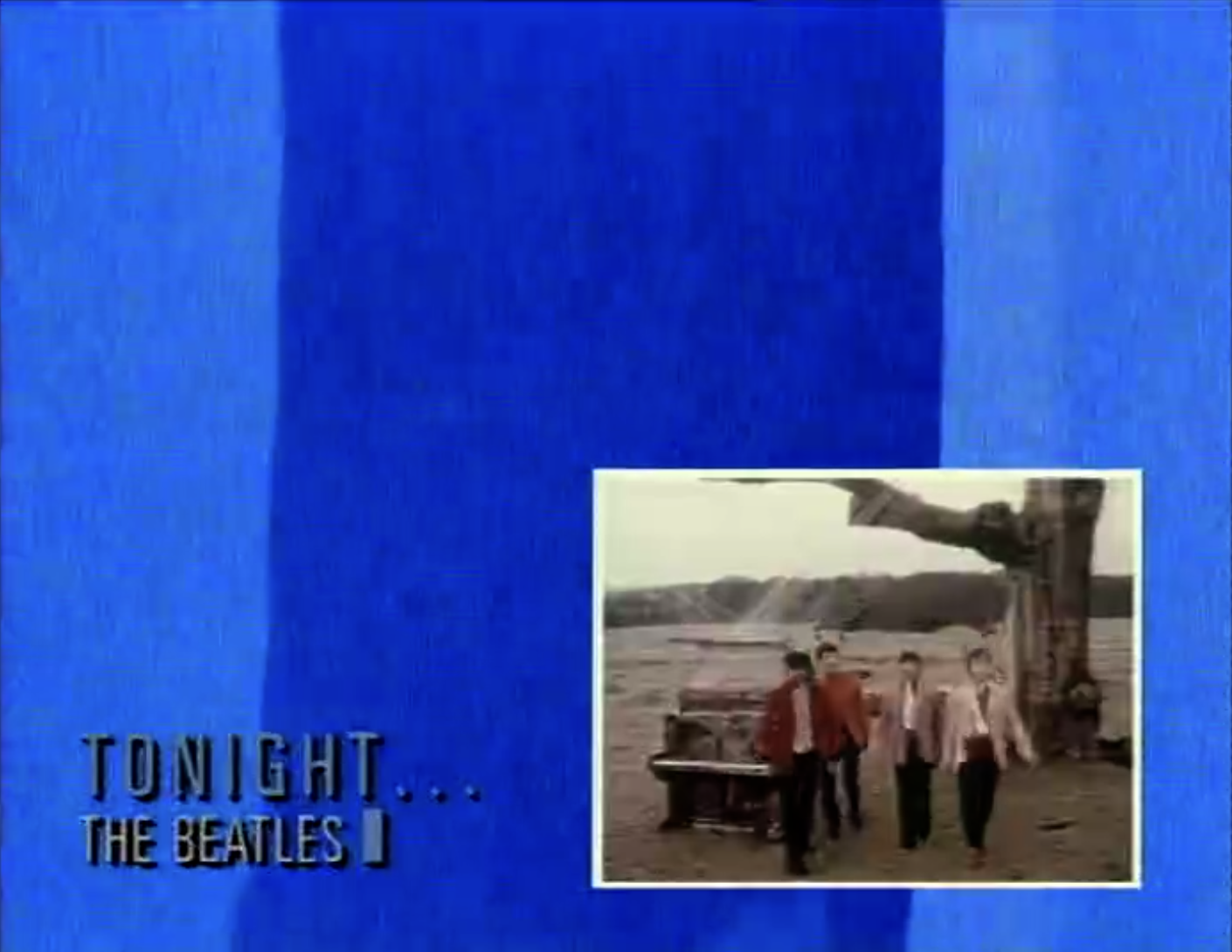

Replacing this was a still image of the new Whistle Test logo, reduced to the corner of the screen, allowing various clips and captions that showcase the lineup for that edition. Accompanying this is whatever music video or performance was selected to kick off the show, whether The Blue Aeroplanes…

…or Eric Clapton.

It feels like the show cannot afford to let a single moment go to waste. In what is a significant reduction in screen time, each edition now runs for only 30 minutes.

The presenting team is reduced to only Mark Ellen and Andy Kershaw. With the loss of additional outside broadcasts to various gigs across the country, Ro Newton has disappeared. With the loss of the video vote and chart rundowns, Richard Skinner is now surplus to requirements, and with the reduction of filmed inserts, David Hepworth is a distant memory.

It doesn’t take a genius to recognise that this is the result of a massive budget cut. We’ll be talking about this more later in this chapter.

I seem to remember nobody was particularly happy with that series.

David G. Croft

While Croft had departed the Whistle Test unit by 1987, his recollection makes sense. Circumstances had conspired to make the final series a pale shadow of the previous three years.

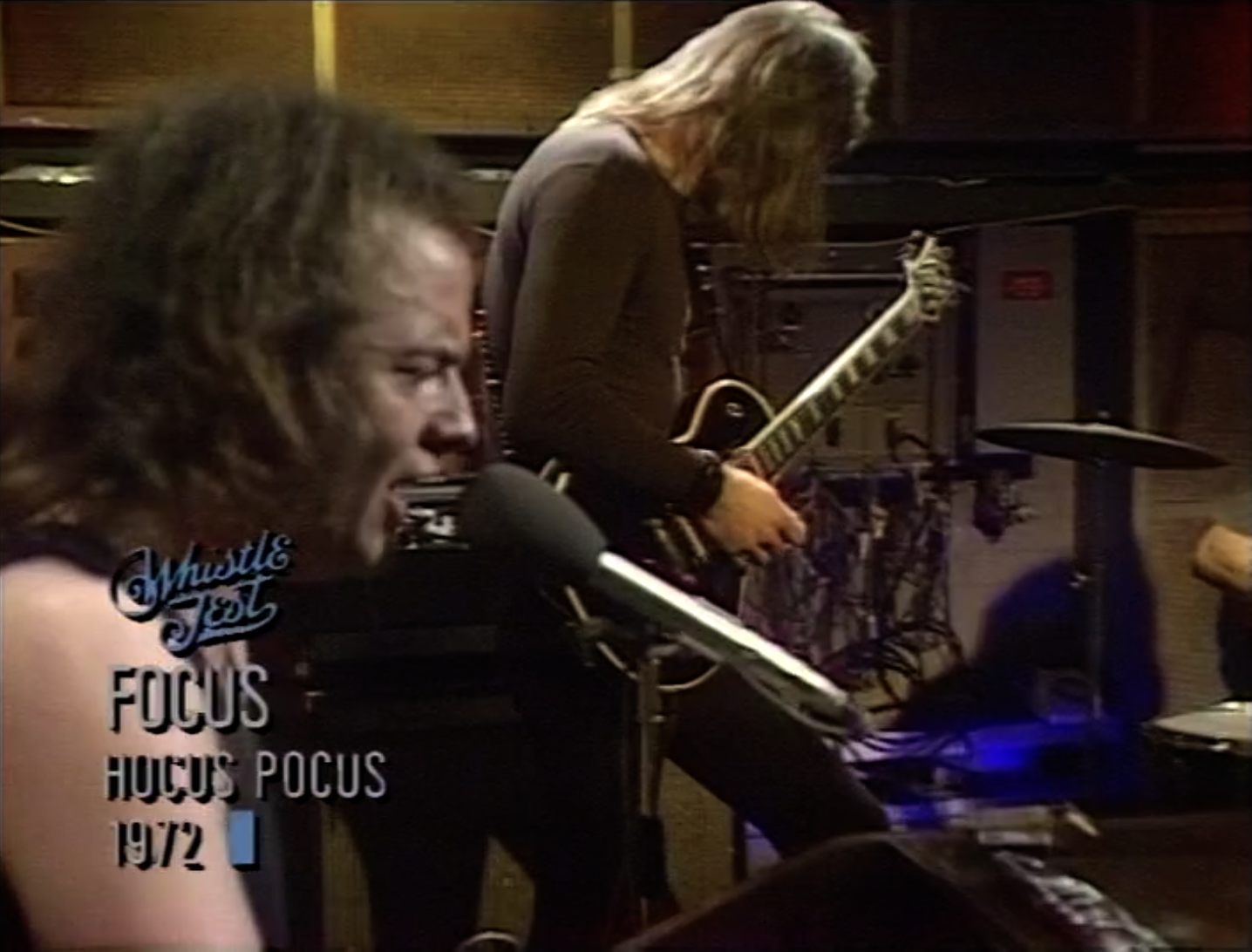

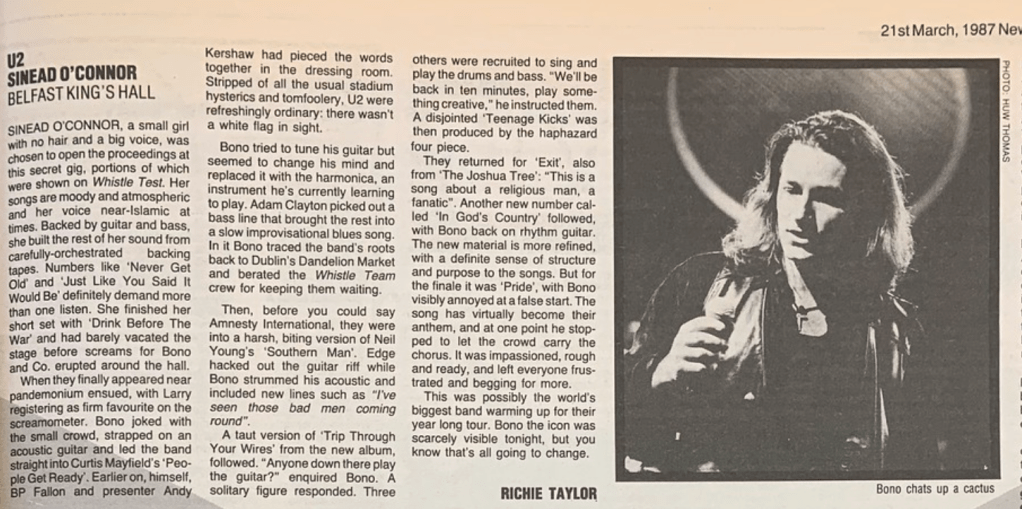

The challenges faced by the production team can be illustrated by an edition from March 1987, with a running order including The Blue Aeroplanes (on video), Sinead O’Connor (live performance), Focus (archival footage), Bob Geldof (on film), U2 (live performance – two tracks), and The Beatles (film). While there’s nothing wrong with this on paper, a 29-minute running time doesn’t serve the show, resulting in presenter links delivered at 200% speed, and a deep exhale once the show was concluded. Once again, the series played second fiddle to the scheduling.

However, an assessment of this final run isn’t all about diminishing returns. There is plenty of interest. Firstly, as long as there was Whistle Test, there would be some excellent live studio performances, showcasing the series’ eclectic approach. The line between rock and dance was crossed by ‘Age of Chance’, rap by ‘Run DMC’, conceptual art by ‘Sudden Sway’, goth-rock by ‘The Mission’ and the geographical course between Zimbabwe and America was charted by ‘The Bundhu Boys’ and ‘Camper Van Beethoven’.

Film inserts included the new country scene, Tom Scholz, and Deep Purple performing in snowy Paris. Dominic Brigstocke described this insert as an “unmitigated disaster“, with the promise of an encore of Smoke on the Water curtailed after a couple of bars, and all of the band bar Richie Blackmore disappearing. However, it would appear that the seeds of discontent were sown years before, as the following press clipping notes:

Whistle Test watchers might have noticed the fabby Dawn Chorus (Andy Kershaw’s sister) following Deep Purple around Paris. Mucho problems behind the scenes, quoth Ms Chorus. It seems that Ian Gillan had taken exception to a question put to him during Purple’s last appearance on Whistle Test, when Andy K suggested the group had only reformed for financial reasons. This was Ian’s “most humiliating experience in 20 years as a rockstar”, Dawn was told by Deep Purple’s manager when he was explaining why Gillan refused to be filmed…

Unknown clipping.

More successful was a trip to Blackburn, and to Tony’s Empress Ballroom, for a feature on the Northern Soul scene. It’s an evocative snapshot of 1980s Britain.

An axis between the established and new acts continued to give the show balance. One week it might be ‘The Cult’ and the other ‘World Party’, whose appearance on the series was a slice of good fortune for Kurt Wallinger’s new unit.

In a contemporary article, producer John Burrowes affirmed a continuing commitment to breaking new acts.

We were supposed to have The Smiths, but due to Morrissey’s grandmother dying, they pulled out. We could have got all sorts of established names to deputise, but I preferred to use World Party a very new act, simply because I like their record. Recently, we’ve also had Age Of Chance, Sudden Sway and the Bhundu Boys, all of whom are so new that they haven’t yet had a hit.

John Burrowes (quoted in 1987)

Still, the comparisons to The Tube continued, with the article suggesting the Channel 4 show was responsible for introducing a larger number of new acts. Fortunately, John Burrowes was there to neatly point out that Whistle Test ran for only a third of the screen time of the Channel 4 show.

Another challenge for the series was the loss of a regular BBC studio in London, resulting in a return to recording in the regions—something commonplace during the ‘Old Grey’ era. However, this became an opportunity to showcase music scenes across the UK, perhaps fulfilling another part of the BBC’s Public Service Broadcasting remit.

The episodes of Whistle Test I’d just finished had felt like the last gasp of a steam engine, its rusting machinery clanking as it waited to be shunted to the knackers’ yard. The Old Grey had overspent so drastically on the series before that, to save money, we’d had to leave Television Centre and pre-record the show using free time in BBC studios in Sheffield, Manchester, Cardiff, Edinburgh and Dublin. The only presenters were myself and Andy; everyone else had gone. I could feel its lifeblood ebbing away, along with its clout and pulling power. The final show featured Wet Wet Wet.

Mark Ellen (Rock Stars Stole My Life!)

An edition broadcast from BBC Manchester’s Oxford Road studios included a lengthy feature on Northern Soul, and another from Cardiff included a discussion about the less well-known Welsh bands of the day, although the inclusion of these filmed inserts (directed by Dominic Brigstocke) might well have been a coincidence.

It was a rotten idea. It’s one of those tick boxy ideas which looked good, but it was the sign of a show that didn’t have a home. It had become perapatetic and no nobody loved it.

It was almost like it was being fostered. Its Mum and Dad didn’t want it anymore so it was being let out to foster parents.

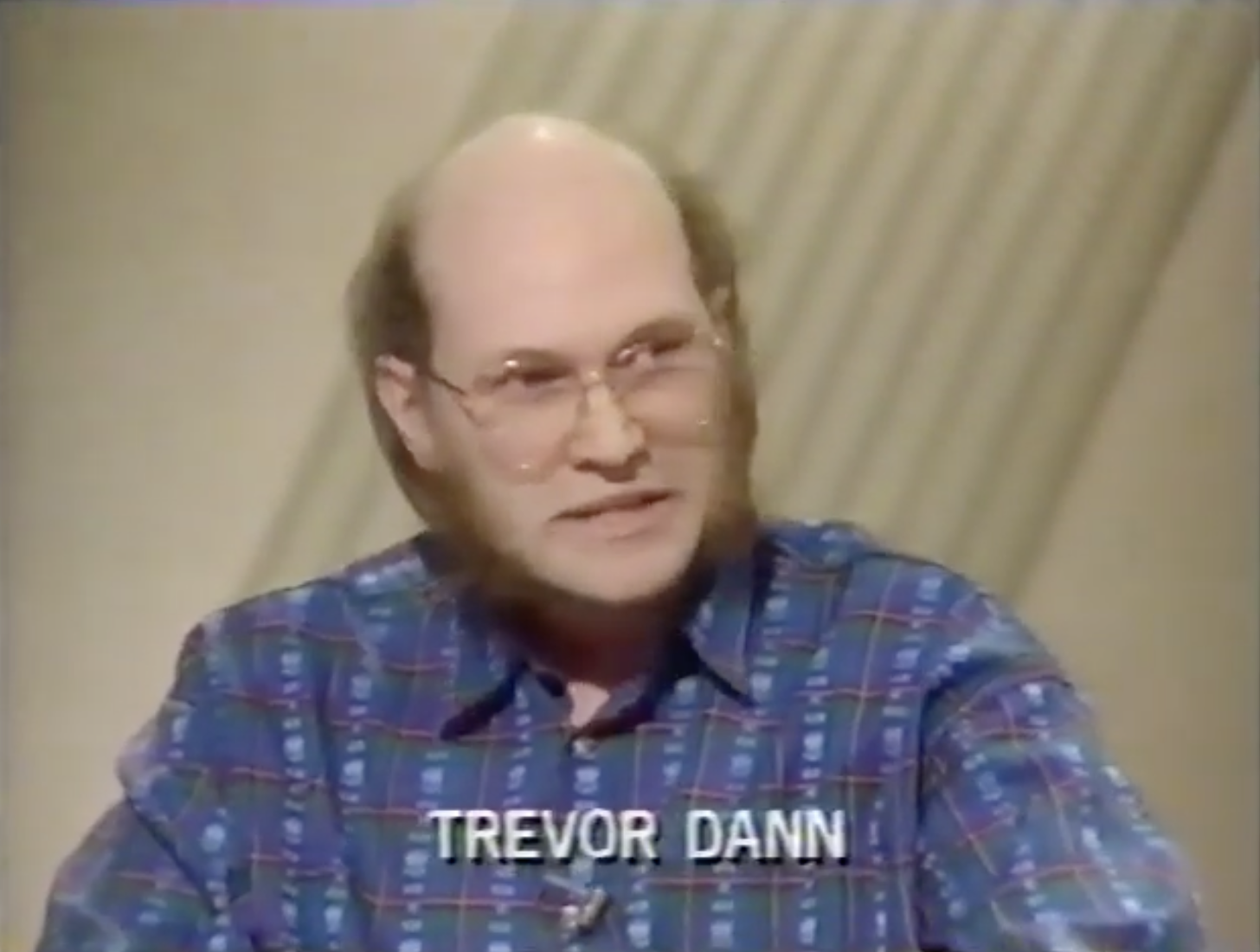

Trevor Dann

The two most notable editions of the series were towards the end of the run, recorded in Belfast and Glasgow – both including a studio audience for the first time since 1983.

The ongoing ‘Troubles’ provided a backdrop for the edition from Northern Ireland, which featured an excellent performance from Sinead O’Connor and a short set (in terms of broadcast) by U2.

I produced the Whistle Test recorded in Belfast when The Troubles was still bubbling. I was proud of the fact I had persuaded U2 to perform live, and gave Sinead O’Connor her first TV.

John Burrowes

The show was recorded at the King’s Hall on 8th March 1987, the day before the release of ‘The Joshua Tree’ and was broadcast three days later.

In terms of importance, the show provided perhaps Whistle Test‘s last hurrah. However, the production was somewhat difficult.

The Whistle Test with U2 and Sinead O’Connor was an Outside Broadcast from Kings Hall, Belfast. It was nearly a lost programme, because the mobile VT recording broke down. I managed to persuade U2 to keep playing for the half hour it took to get things working again. The lucky audience got a free concert, unfortunately, most of it was not recorded.

John Burrowes

The Scottish leg of the journey was, in fact, the very final regular edition of Whistle Test, transmitted towards the end of March 1987.

The show was broadcast from BBC Glasgow. Once again, The Smiths cast a shadow on proceedings, with Mark Ellen apologising to viewers that the band was not appearing due to “personal problems“. A filmed feature on Glasgow Gunslingers at the Grand Ole Opry, formed 50% of the Scottish themed content, with the final live studio performance going to a band that was up and coming at the time – Wet Wet Wet.

I liked the Wets who came from my hometown of Clydebank – not generally a Whistle Test type band. I think I may have suggested them for the show.

May Miller

The crews in Glasgow were pretty enthusiastic as they did a local show called FSD which was quite wild. So they were less moany about my hand held shots and very versatile. I got to know and respect them all very much when I moved back to Glasgow in 1988.

May Miller

I guess it was a highlight for me, in that I got to direct one of my favourite bands – the live audience really added to the atmosphere. I can’t remember, but I would imagine they would NOT be one of Andy’s favourite bands at the time.

May Miller

Yet inevitably, the headline of this final series is one of reduction. John Burrowes commented on a choice faced by the production team, and whether Whistle Test would be taken off the air.

‘Whistle Test‘ was offered two slots; half-an-hour at 8pm (a prime time in terms of BBC2, the corporation’s less mainstream network) or a longer show after 11pm. Opting for the former meant dropping a regular outside broadcast feature, thereby only permitting one live act per show.

No programme has a God given right to continue, but there’s no reason at the moment to think that the ‘Whistle Test‘ might not return.

John Burrowes (quoted in Music and Media, 1987)

Perhaps the music press and production team had an inkling that its days were numbered? But nothing was certain. During the opening link to the final regular edition, Mark Ellen announced the last of the current series. Presumably, the decision to axe Whistle Test had either not been made, or the heads of department were waiting for the right time.

I don’t think we knew the programme at BBC in Glasgow was to be last at the time, although we did know about the end of Network Features and joining the Entertainment Department. The show was now 30 minutes and had to go round the country for studio space. It was quite a good adventure visiting the various BBC studios and audiences.

Karen Rosie

I don’t really remember how or when we found out. I was pregnant at the time – something I managed to keep quiet far into my pregnancy. I was still directing live shows including concerts with The Cult, and The Communards, and I was six months pregnant when I directed the Wets.

May Miller

This final regular edition of Whistle Test was transmitted on 25th March 1987. A couple of ‘specials’ known as Whistle Test Extra followed in April, but bar one last hurrah, that was it.

Andy, myself, and Dave were called to a Chinese restaurant by Michael. I remember this very vividly actually – Silk and Spice, April 1987.

We could all read the writing on the wall, the whole thing had kind of run out of money I think. Within seconds I can remember people saying “It’s not coming back? Oh, it’s absolutely fantastic!“

Mark Ellen (BBC DVD commentry).

Mike Appleton (quoted in Rock and Pop on British Television)

It had been going 16 years, so it was difficult to keep it fresh anyway, and let’s say I didn’t put up a fight for it. It came to a conclusion, which was probably as well. If it had gone on any longer, it would have probably dragged on. Certainly, I wouldn’t have been there and it was my baby so I didn’t really want any nannies looking after it.

Obscured is David Turnbull on guitar (Network Features producer) and Rory Sheehan on backing vocals (part of The Rock ‘n Roll Years production team.)

“Trevor Dann didn’t take part as he said we were terrible. Which no doubt we were!!” (May Miller)

I just think she (Janet Street-Porter) came in and went Whistle Test. That’s rubbish. We’ll get rid of it. We don’t want that anymore.

David G. Croft

May Miller recalled Janet Street-Porter being very keen to bring in women into her team where possible, and being very helpful when Miller decided to abandon the capital, in favour of a return to Glasgow, but continuing to undertake some work on DEFII.

She thought, like everyone else, I was mad going back to the wilds of Scotland.

May Miller

For others, the changing of the guard could be a brutal process.

What happened to me was I went out to LA to make a film with Fleetwood Mac, which I’d been trying to do for years. While I was over there Bill Fowler (plugger) rang me up and said “Hello, I don’t know whether I should tell you this, but I’ve just been up to your office and all your stuff is in a skip in the corridor, and Janet Street-Porter has moved in.”

I was moved out. I came back to edit my film, and rather despairingly I went up the stairs and there indeed was two of those green kind of BBC trays where they move everybody’s stuff, and they were both just sitting there. There were things I was quite fond of, like an award for something, and it had all been tossed into these skips, and I had to rather sadly move them out, put them in my car and drive home.

Trevor Dann

I was still working on the show when it was cancelled (thereby making it very tricky to get a job.) Very fortunately for me, the producer of Film ‘86 was pregnant and they needed someone to cover. Working with Barry Norman was a dream job.

Dominic Brigstocke

The BBC at the time was very complacent and yet to be shocked by the influx of independent productions. Everything was very much relaxed – if a show was cancelled, you’d just be moved to another. Most people had jobs for life and very generous pension arrangements. When Whistle Test was cancelled, most of the production team were just moved to Wogan. I was on a two year contract, then a four month contract, then rolling one year contracts, so my world was less secure.

Dominic Brigstocke

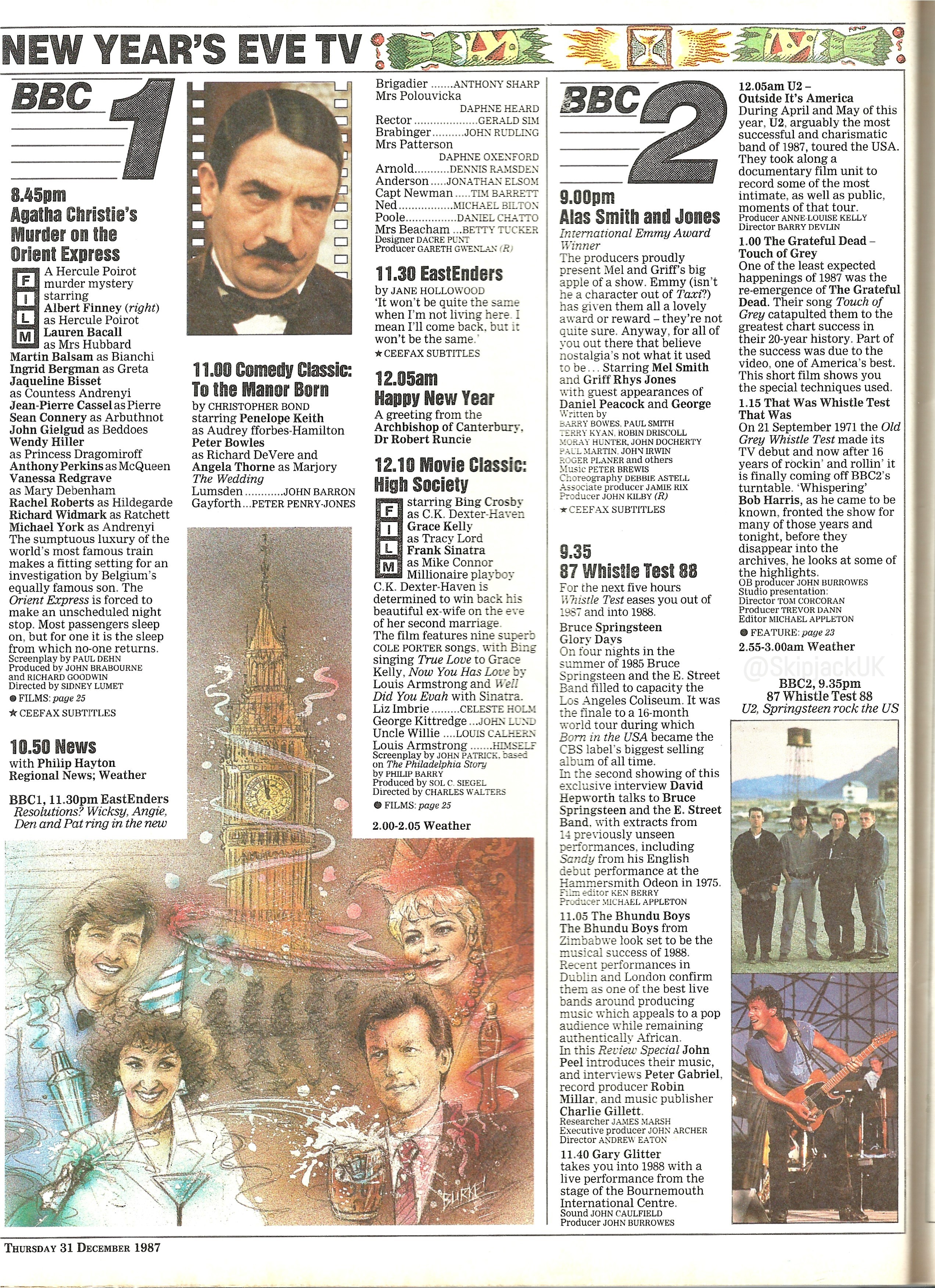

Music continued to feature on BBC2, notably with No Limits, a pre-recorded jaunt around the country, featuring music promos and a chart rundown. It was dubbed ‘the world’s fastest rock show‘. It catered for a younger audience in a way that Whistle Test was never able to. But the focus of that series wasn’t live performance, and by the end of 1987, No Limits was gone too, with the final edition screened just over a week before the final Whistle Test extravaganza on New Year’s Eve 1987.

The final Whistle Test hurrah – the five-hour live extravaganza – was titled 87 Whistle Test 88, and included everything from Bruce Springsteen to The Bundhu Boys. The final compilation of highlights was entitled That Was The Whistle Test That Was.

Ro Newton (back for one night only) drew the short straw by linking a performance from a certain disgraced rock star, while Bob Harris made a final return to where it all started – studio ‘Pres B’, the tiny living room sized presentation area, and waved “bye bye” to Alma Player right at the very end.

Just before 3am, on 1st January 1988, as quietly as it had started, Whistle Test bowed out.

So that was 1987. But what did the following New Year’s Eve look like, as 1988 drew to a close? Did Whistle Test take all the music with it?

A glance at the schedules presents live music as something of an afterthought, except if you’re a fan of the Eurythmics or David Bowie. Both concerts that straddled the midnight hour were no longer in-house BBC productions, being directed for independent companies by noted music video director David Mallet, and The Tube alumni Geoff Wonfor.

One can’t ignore the idea that it wasn’t just Whistle Test that was the casualty of live music, but also the wider departments within the BBC – a portent to the looming ‘Producer’s Choice’ and shake-up of BBC operations.

Those following years were either barren or, at best, uneventful for the terrestrial rock/pop music fan. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that Later with Jools Holland, a show that Trevor Dann described as “Son of Whistle Test“, and, to a degree, The Word, placed live studio rock music performance firmly back on the television radar.

As with most things actually, the moment it ceased to exist, people developed an enormous affection for it.

Mark Ellen (BBC DVD commentry)

Several possible arguments explain the ultimate demise of Whistle Test. The easiest of these is the common television battleground – due to scheduling, competition, and an evolution in both music and broadcasting, the show stopped bringing in the viewing figures required to sustain the series.

As a producer on it all those years, I felt I was managing decline. It was a late night brand that would probably still be running now, had the BBC had the courage to stick with it but, once you muck about with those things, you ruin them.

There are, of course, totally different audiences at 10:45 and 7:30 or 6:00pm – exactly at the time when nobody could watch it. It was very much the same as what they did years later to Top Of The Pops, when they moved it to Fridays. It was a misplaced reinvention, and the skids were under us from the minute we did it!

Trevor Dann (quoted in Popular Music and Television in Britain)

I have sympathy with Dann’s argument that retaining the late-night version of Whistle Test might have resulted in a very different outcome. However, I don’t believe the overall revamp was a failure. In fact, both programme format and performances in that first live series of 1984-85 won audience and institutional approval. But Dann’s comment about different audiences at different times is crucial, and the shifting timeslots destabilised the series.

What is most certain is that the BBC was shedding its skin in 1987.

Graeme MacDonald, who as controller of BBC2 commissioned the new Whistle Test, left his post around the time of the ‘Zircon’ affair – further straining relations between the BBC and Thatcher’s government. In his place was Alan Yentob, who quickly determined that the channel was “a bit dull and middle-aged“. Yentob was instrumental in bringing in Janet Street-Porter from Channel 4. Her acclaimed Network 7 was admired by the new controller for its fresh approach, energy, and vigor.

A warhorse at that time was the Old Grey Whistle Test, which was more for university graduates in a way, than it was for youth really.

…it’s pace was slow, and it belonged to another era.

Alan Yentob (quoted in The Story of Light Entertainment, BBC 2009)

You know people don’t come into jobs and go “I entirely agree with everything my predecessor has done.” They go “Oh, I’ve got the job now so what can I change? Who can I sack?”

(BBC2 controller) Graeme MacDonald did not get Whistle Test. It was not his thing, and that’s why he was responsible for the demise, in my view. Brian Wenham (MacDonald’s predecessor) was a supporter of Whistle Test.

Trevor Dann

There was also a departmental restructuring at play.

The writing was seemingly on the wall for Whistle Test. The department called Network Features, which spawned the programme was being split up in a management shake-up.

It was a somewhat cosmetic thing because everybody was going in to different departments and all we were losing in fact was the name Network Features, but it did mean that we were in danger of losing that autonomy which had been so vital to our existence through the years.

Mike Appleton (BBC DVD commentry)

Network Features had been abolished, and all of us had been moved into Light Entertainment with Jim Moir.

I‘d forgotten this, but Mike Appleton’s argument was “You can’t put my team into Light Entertainment!” We wanted to be in Music and Arts which then was Alan Yentob’s department.

So, the idea that people like me and John Burrowes were moved over into Music and Arts was not happening, because they didn’t want us. We were the last people they wanted. You know, we were a bit red brick and they were a bit, you know, Oxbridge. We weren’t going to help them at all, or at least their image.

Trevor Dann

So, were there bigger forces at play in the decision to shuffle departments, and how had times and tastes dramatically changed in the first half of the 1980s?

The central exhibit in evidencing the death of Whistle Test, was a fascinating series of articles published in the NME on 7th March, 1987. These critiqued Whistle Test, and The Tube amongst others.

Looking back, the TV Pop in Crisis was a really interesting snapshot of times past, and in its assessment of Whistle Test, the NME’s prosecution pulled no punches.

In 1987, Pop TV is also confronting a crisis of form, a problem that is most readily visible in the smug presentation of adult derived “couch” shows like Whistle Test. Despite the removal of the self-deprecating words ‘old’ and ‘grey’, Whistle Test still seems more at home with history than with the present. It deals confidently with the rock giants of the past but is virtually incapable of dealing with new and contemporary music, whether it’s the exciting disruptiveness of hip-hop or the creative disparity of post-punk. Whistle Test seems incapable of shaking modern music into TV life, as it lumbers on apparently restricted by financial cut-backs, corporate bureaucracy, the institutional stasis of the BBC and the dull conservatism of its own form.

Stuart Cosgrove (NME, 1987)

The dedicated article about Whistle Test itself – Whistle Pest – portrays a ‘them vs us’ battleground with considerable ease. Where Jimmy Somerville looks bored to distraction, it is likely due to the classic rule of thumb of film and television – for one minute of footage, there are 10 minutes of hanging around. However, the boredom is portrayed as being due to the programme itself, with Sean O’Hagen even referring to the Whistle Test camp as “you lot“.

Described as the “grandaddy” and “aged and gaunt”, the series draws inevitable comparisons with The Tube. Andy Kershaw flies the flag for Whistle Test, backed up by producers Trevor Dann and John Burrowes, with much of the discussion centred around the differences in style between the energy of The Tube and the staid Whistle Test. There’s little acceptance of each other’s stylistics.

Amidst the warfare, there are occasional moments of amusement. During an attack on the presentation team, Dann attempts to soften the aggression with an almost conciliatory note about Mark Ellen not obeying the rules of television grammar. “He’s no Desmond Lynam.”

Mark was very clever and very precise about “You can’t say that, that’s not the right word, that’s too many adjectives” – all those details. However he didn’t like it when the television people would say “Would it be would it be absolutely too much if you could just say A and B and not wave your hands around?”

Trevor Dann

Presenting styles aside, perhaps there was merit in some of the NME’s arguments. The financial and institutional limitations imposed on Whistle Test might well have diluted the potential of the show. Perhaps it was caught between the need to be ‘across the board’ and not having the means to execute this, due to a lack of faith by the BBC. The NME’s final argument that Whistle Test should do what it does best, and admit to being an ‘adult’ rock show, feels perfectly reasonable as a proposition.

It’s an article with some merits and a few inconsistencies that fit in with the central “TV pop in crisis” thrust of the feature. There is an olive branch, with the recognition that Whistle Test is “that” more specialist rock programme, yet it is trapped within its own meagre budget.

I think Whistle Test as a programme needed to be cherished. The people who had launched it and looked after it in its early days thought a lot of it, and they really wanted to sustain it. But by the time we got to the middle of the 1980s there was nobody really in a position of authority saying “Yeah yeah, we’ve got to keep Whistle Test because it’s just great.”

I remember saying at the time “What we really need is for somebody to love it as much as they love Songs of Praise – it sounds flippant, but they’ll never take that off.

But it wasn’t to be.

Trevor Dann

But one thing that NME was right on the money with was that, by 1987, TV pop was in crisis.

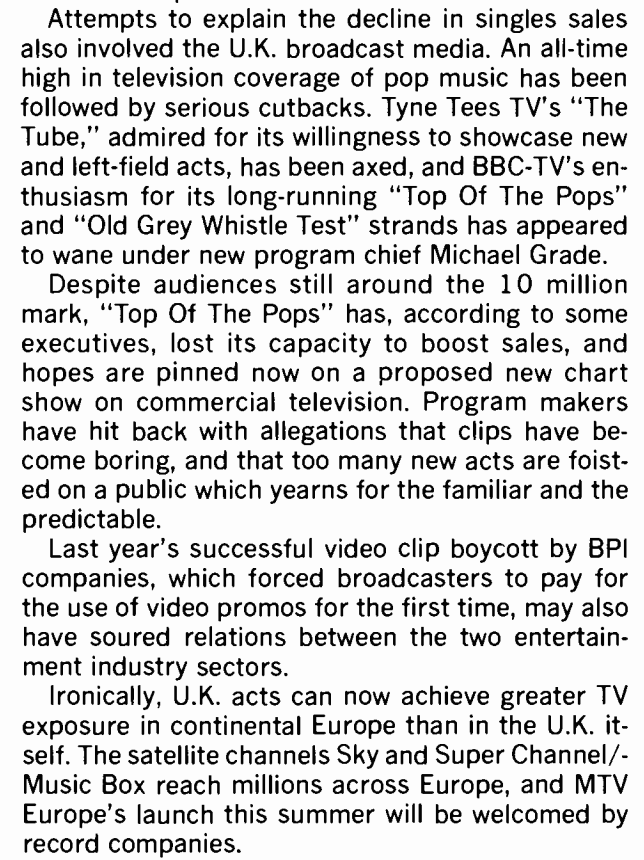

The BBC has recently been accused of a lack of commitment to popular music since the arrival of Michael Grade as Head Of BBC TV programmes. The main impact notice- able to viewers has been that the weekly “Top Of The Pops’ show has been reduced to 30 minutes per week. According to spokesperson Ann Rosenberg there is nothing sinister in this – it was purely a case of “streamlining” all light enter- tainment programmes to either an hour or half-an-hour.

In response to the question of why there seems to be less music shows on tv, Rosenberg says: “The music world doesn’t appear to have thrown up anything of note recently which would attract the kind of viewing figures we want. There are very few people today who are genuine entertainers like Shirley Bassey or Cliff Richard for instance – nowadays the tendency seems to be for groups.” So why not do a Monkees-style series with a group like the Housemartins, for example? “Well, that has already been done by the Monkees. We’re look- ing for something new rather than going backwards.”

“Top Of The Pops’ is the longest running tv pop show in Britain, of course, and has had little variation in its format, which is simply to reflect the top selling singles in the chart each week, along with the highest climbers and an occasional new single, usually from an estab- lished artist. As such, it is not regarded as a medium for discover- ing new talent, a role fulfilled at the BBC by ‘Whistle Test’, which has also been reduced to a half-an-hour for the current series.

John Tobler (Music and Media, 1987)

David G. Croft echoes this recollection, offering a wider context:

Mrs. Thatcher had decided to BBC was too big. And the BBC, instead of standing up for itself… well, it was the beginning of it not standing up for itself. So it said it would close two departments. The Music Group and Network Features.

I believe there were two choices. We could have gone to Music and Arts, or we could have gone to Light Entertainment who had promised us we could be a unit within within the department. That’s where we went and that didn’t happen. And lots of people began to leave.

It was a shame because Network Features was a very interesting department, full of very talented generalists who wanted to make all kinds of different shows, not just one particular genre.

Once the department broke up, those folks were scattered to the wind really.

David G. Croft

So, the new Youth and Entertainment Features unit was established. The new DEF II strand was on its way, and dance music was emerging as a considerable force. This required new programming.

And that required money.

Whistle Test money.

The writing was on the wall.

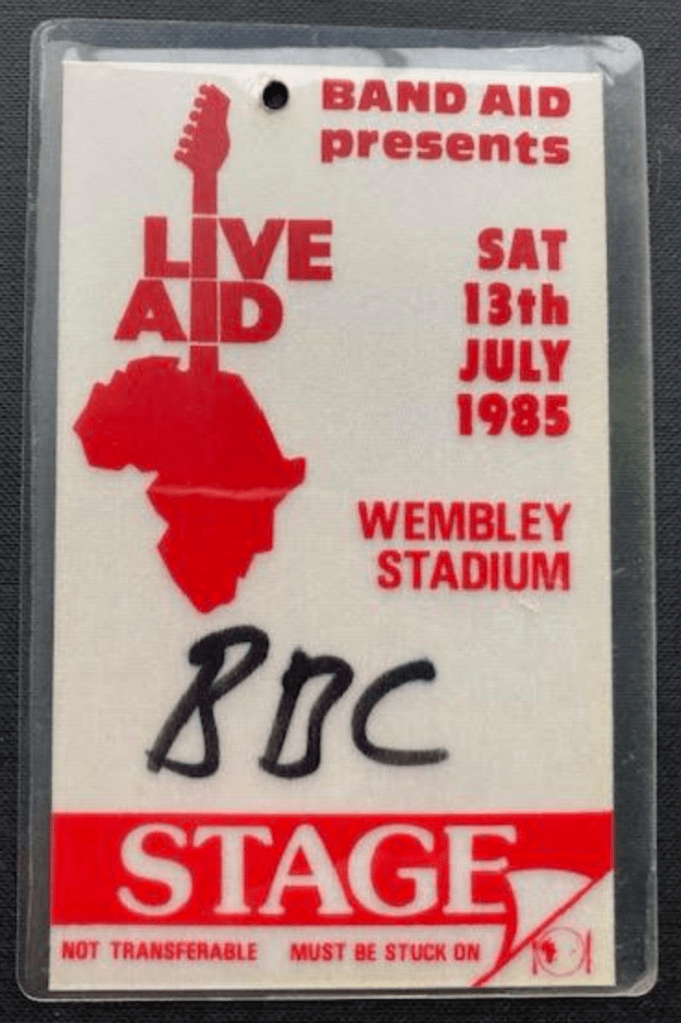

Against all odds, we had survived the period of punk. We peaked with Live Aid which was put together by the Whistle Test team, and in a way I suppose we’d exhausted our territory.

There was a new type of music beginning to come in which was dance music and was club oriented and, for my money, not as successful on television as the music that had come before it – great in clubs and great to dance to, but as a spectacle, for me anyway, less satisfactory.

Mike Appleton

Yet, there may be even more to the manoeuvrings that led to Whistle Test‘s demise.

Perhaps the root cause was – as most things are – a lack of money. In 1981, a new license fee settlement with Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government came into force. The effect was felt across the BBC. Coincidentally, the following year saw a reduction in the Old Grey Whistle Test in terms of its weekly run, from three quarters of a year to less than a quarter.

Then came the revamped, live, early evening Whistle Test of 1984-5. This will have received an increase in budget, paying for the presenting team, live feeds, and two bands, not to mention the Garcon lamp! Once again, timings seem to play a part. Thatcher won a second term as Prime Minister, and the next license fee settlement that came into effect from 1st April 1985 was £58 for a colour television license set, far below what the BBC had hoped for.

It was inevitable then, as it is now.

Accordingly, the BBC Director-General set up a small group, chaired by the Director of Finance, to conduct a radical review of the BBC’s activities. The task of the group was to suggest how the BBC’s resources might best be concentrated on the essence of the BBC – the functions that were integral to the corporation – programme making and public service broadcasting.

The resulting report was wide-reaching in its impact on the departments across the BBC. Senior governors and management identified priorities, including the introduction of a daytime schedule on BBC1 from 1986, and regional restructuring.

Once again, it was the following financial year that saw Whistle Test reduced from 12 x 60-minute editions to 11 x 30-minute editions, before cancelling it completely.

Of course, it wasn’t just Whistle Test that felt the pinch. Doctor Who fans will be familiar with the story of how the arrival of Michael Grade at the BBC, resulted in a shake-up, and sweep-out, of various shows and schedules in his role as director of BBC Television programmes. And in the case of Doctor Who, a dramatic reduction.

But it might not simply be a case of budget reductions on specific shows, there might have been another factor at play, involving both the music industry and television broadcasters.

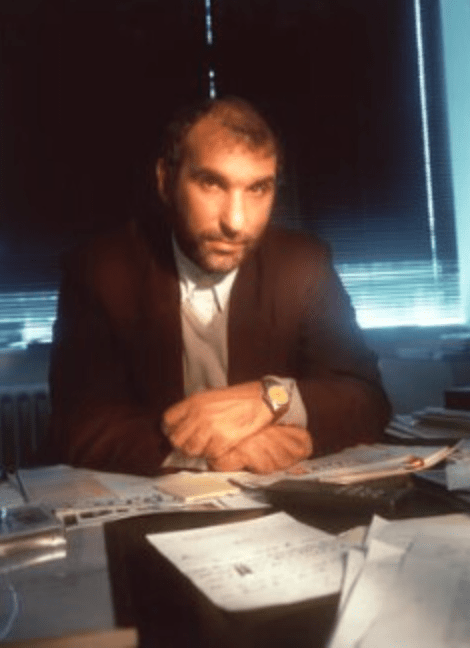

David G. Croft recalls a feeling that “the “mood music” from the BBC’s ‘sixth-floor’ management, was the rock music on TV had its day. The music press certainly felt that there was change afoot, and it was not uncommon for articles to both bemoan a perceived reduction in the value and production of music television within the BBC, and include a big picture of Michael Grade standing outside of BBC Television Centre.

In addition to a dwindling Whistle Test, Top of the Pops was also reduced, from 40 minutes to 30 minutes. According to press clippings of the time, there was a fear that the show had lost its capacity to boost sales, and a war of words between industry and broadcasters had emerged, based on the debate that video clips had become boring and that too many new acts are foisted on a public which yearns for the familiar and the predictable.

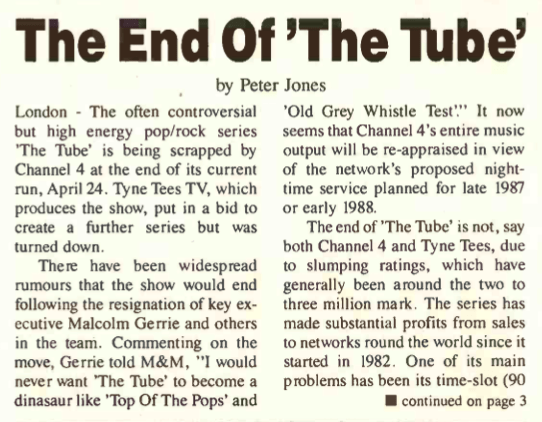

It’s possible to speculate that this might be a factor in why The Tube ended at the same time as Whistle Test. On the surface, internal politics was the cause, but it can’t be ignored that commercial television in 1987 also saw a radical shift in programming, including ITV’s TOTP competitor – The Roxy – which didn’t last long.

An interesting acknowledgement of a perceived BBC policy change happened in late 1987 when Top of the Pops producer Michael Hurll joined Trevor Dann to appear on the BBC’s Network – a ‘Right to Reply‘ show giving audiences a chance to comment on BBC programming. (Yes, Whistle Test can be glimpsed in frame no.127 of the title sequence, fact fans)

What a shirt that was.

Trevor Dann, about his appearence on Network (1987)

Anna Ford introduced the show by noting that there was a lack of serious feature-based rock magazine programmes on television, and there was a vacuum left by the demise of Whistle Test and The Tube.

Viewer Barry Ryan made a film outlining where he felt television was going wrong. This mainly centred on the idea that audiences were being exposed to the familiar, rather than the unfamiliar. The BBC was singled out for being obsessed with the Top 40, which was “firmly entrenched in the schedules“.

Whistle Test, for the first time, was referred to in the past tense.

RYAN (V/O): Even the BBC’s evergreen Old Grey Whistle Test lost the ‘Old’ and the ‘Grey’ and improved, before being first reduced to 30 minutes and finally lost. Of course, Los Lobos are a household name now, but were unheard of when they first appeared on the Whistle Test.

Andy Kershaw and Morrissey were interviewed as part of the feature. Kershaw saw rock television as a “pretty boring world” without the unfamiliar. Morrissey saw the lack of serious programming as “…totally political. It’s like deliberately not reflecting the times, deliberately not reflecting anything that occurs in 1987“.

What followed was a studio discussion between Ryan, Hurll, and Dann.

Hurll commented on the small audience figures for Channel 4 music output, referencing The Tube, Solid Soul and ECT, and posed the question of whether the schedulers and controllers could justify that sort of product, particularly during prime-time television slots.

Then the discussion turned to the evergreen balancing act between audience and money for minority interest programmes. At one point, Anna Ford responds to Trevor Dann’s comment about Whistle Test’s viewing figures by replying, “One and a bit million people watching any programme doesn’t seem to me to be too disgraceful.” Cue a slightly wistful and somewhat surprised reaction from Dann.

Trevor Dann was introduced as someone who was “in control of a new pilot” that was potentially going to resolve all of Barry Ryan’s points. “Possibly so” was Dann’s guarded reply.

In fact, Dann and John Burrowes were invited to make a pilot each, although ultimately this came to nothing, with a new controller of BBC2 announced not long after Network was aired. Dann pointed out “...we don’t know who’s going be running the channel that we work on in the next few weeks, and we are in their hands in a way, because if we don’t get that kind of support that we need from up there, then we won’t be able to make this kind of programme.“

Dann made the point that “…the BBC and the other television companies have a duty to have a little squint around the corner“, before noting that “…any programme that doesn’t pull an audience these days isn’t going to be on, is it? Unless it’s in an area where it’s considered to be art. One of pop music’s great problems is that in a way it’s too successful, and because the most successful part of it is perceived to be entertainment, therefore all of it is perceived to be entertainment.”

Towards the end of the discussion, the blood pressure is raised a little, with Dann responding to Ryan’s questions about age. “Don’t go thinking that pop music is just for young people. That’s a very arrogant point of view. Young people are a declining audience.”

The edition of Network was a fascinating time capsule, for two reasons. Firstly, it captures the 1980s sensibility of studio audiences seriously trying to resolve the issues of the day (prior to Kilroy and The Time The Place.). Secondly, the edition plays out like a microcosm of the musical and broadcasting events of 1987 – questions are raised about audience and attitudes, and ultimately, the shuffling of the Whistle Test team and the departments within the BBC.

Despite Trevor and I making very different, separate pilot offerings to replace Whistle Test, Janet was given our pot of money and even took over our old office.

John Burrowes

By 1988, Whistle Test was all but forgotten by the BBC, which had evolved rapidly. Mike Appleton returned to Wembley to oversee the Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Concert, before moving on to become Managing Director of The Landscape Channel, where he retained the same degree of authorship as at the BBC.

(Nick) Austin has instructed Landscape managing director Mike Appleton to provide programs of the same quality and musical validity as he previously achieved when working on BBC TV’s “Whistle Test” series. This means a ground rule whereby everyone knows that music selected for Landscape conforms with “a qualitative decision” made by the channel and nobody else.

Unknown press clipping.

Mike could see no future in Light Entertainment, and went off to create Landscape TV. We kept in touch and remained good friends until his death.

John Burrowes

Over the decades, an established history of latter-era Whistle Test has emerged. The common lore includes the following:

…it should not have tried to compete with The Tube,

…it should have stayed as a late-night hideaway,

…if it remained true to its earlier self, it would have still been with us today,

…those last years weren’t a patch on the Whispering Bob era.

These are all perfectly reasonable and understandable viewpoints. And they can be read, at best, with a degree of truth to it, or at the very least, as subjective.

However, the riddle of the Whistle Test‘s final years is something of a Gordian knot. On one hand, some criticised the show for being old-fashioned, yet others lamented the fact that it departed from its traditional formula.

The series was criticised (by some) for being too earnest, with a lamentable lack of style. Yet, it wasn’t the same show when the 1980s forced it to let loose and up its stylistic game.

It removed two words, yet those words frequently came back to haunt the rebrand.

Trying to change the name by stealth is one of those things that brands always do when they’re worried they’ve been around too long, and it never, ever, works.

It’s similar to replacing the Area Code 615 version of the theme with the clanky synthy one. In time all the supposedly dated elements become “old school” or “classic” and “legendary”. That didn’t happen with Whistle Test until it had been dead and gone for years, and was reborn via YouTube!

David Hepworth

Whistle Test feels like a case of ‘do or die.’

The creativity, innovation, and bravery of those final years were quite unlike anything the show had experienced before. The video vote, chart rundowns, mix of presenters, the move to live television, visual appearance, pace, and the general removal of any reference to its ‘Older’ and ‘Greyer’ history, was an exercise in proactive innovation. Some saw it as a shift towards entertainment rather than music. Yet, it’s hard to sit still when everything else is changing around you.

And, it is fascinating to consider the transition from the OGWT, with its late-night, small, exclusive audience, and a large amount of freedom to do what it wants, to the all-new, all-live Whistle Test, where a prime time slot results in higher stakes and increased scrutiny.

There was the question of whether the move to a live format made a difference. On one hand, it opened up opportunities for audience interaction and a shift in format. The counterargument is that the essence of the show was studio performance, so it simply didn’t matter enough.

The reboot of the show had been well intentioned and lots of what was done was genuinely cool by the standards of the day, but whoever thought a music show on BBC2 would do well early evening against EastEnders needed their head examining! And the passion of TV producers for doing things ‘live’ (because it’s really exciting to do) when the audiences can’t tell the difference is unjustified.

Dominic Brigstocke

It was bravely rescheduled by the BBC, only to be sunk by another bit of brave scheduling, involving a soap opera also made by the BBC. And that impacted all the scheduling decisions that followed, none of which answered a critical question of those final years – who was Whistle Test now aimed at? The closest we can come to an answer is a broad church. Perhaps too broad?

Its core audience was effectively told to go away while we desperately wanted young people to watch a brand they were never going to connect with.

Trevor Dann

It’s also fascinating to explore Whistle Test within the context of being an ‘in-house’ BBC production, with all the institutional advantages and disadvantages; the creative dynamics and tensions; the occasional clash between the directors and technical departments over handheld vs pedestal camerawork.

The ‘BBCness’ also extended to the choice of presenters, many of whom were involved with Radio 1, or other television shows within the corporation. There was reference (and reverence) to John Peel, humour directed at BBC policy, such as the use (or otherwise) of “harmless fizzy pop“.

There were nods to other BBC2 shows from Top Gear – “Wait for it, William Wollard fans”, to the sound levels in the studio – “I bet they could hear that up in Newsnight.”

There were connections between Whistle Test and the Top 30 chart rundown, issued on a Tuesday and exclusive to the BBC. Even the Ceefax Top 10 behind Richard Skinner was unique to the corporation.

Whistle Test also throws up interesting questions and tensions surrounding authorship, such as the founding producer reluctantly giving up a degree of control and handing over to two production teams. It’s also interesting to note the different approaches between those two teams, one led by an established television producer/director, and the other by a rookie producer who had come from radio. This mix of experience and inexperience extended to the wider team, both in front of and behind the cameras.

Looking back, I get a sense that no matter what innovations were pursued, and no matter how true the show remained to showcasing live performances, it was a case of damned if you do, damned if you don’t – the comparisons between Whistle Test and The Tube, and the resulting perception by the press was always going to stick.

The sound was good. But others compared it to a supposedly 96-track mixing desk in a studio in Newcastle – regardless of whether it actually needed that number of tracks.

The show was worthy, but the press was more interested in how it was crewed by experienced broadcasting technicians and engineers, rather than music fans. This disregarded the fact that The Tube was also crewed by television engineers in Newcastle.

The series was supposedly killed by The Tube, yet both shows bowed out at the same time.

The producers and editors often seemed to be on the back foot when justifying the show’s existence to the music press, yet it co-existed with its main competition fairly harmoniously, and rarely crossed paths.

The BBC wouldn’t commit any resources to publicity, whereas Channel 4 put huge amounts of money behind The Tube and it became this hip show. We were always struggling with a feeling that we weren’t hip.

At the end of the office. I had a chart and every week I would go and draw that so we could look at the audience comparison between the two shows and there was really nothing in it.

David G. Croft

The sense of competition – understandably enough – came largely from the music press, and pressure was felt by the production team. It was the stylistic and tonal comparisons between the shows that became the essence of the competition, more so than scheduling, budgeting, or viewing figures. The Tube gave rock TV (and Whistle Test) a nudge, just as Whistle Test gave ‘serious’ rock a nudge (and indeed, a voice) back in the early 1970s. However, comparisons make a good story, while completely disregarding that they were two completely different shows.

In fact, both shows reflect two different facets of public service broadcasting. The Tube fell firmly within Channel 4’s remit of being contemporary, innovative, risk-taking, and catering for so-called minority interests. Whistle Test encapsulated the BBC’s mission to educate, inform, and entertain, and was more altruistic in its feel.

The battle was was fought over terrain that didn’t matter. Whether the BBC has a show that has more viewers than The Tube is not important. What’s important is “Does it have a show that would not happen otherwise, and of which is worthy of public financing?“

Trevor Dann

There was room for both, but the perception of Whistle Test (i.e. earnestness) never seemed to leave the show. The NME of 1987 felt that the show was incapable of engaging with new music, yet the eclectic lineup of that last series included ‘Sudden Sway’, ‘Run DMC’, ‘Ace of Chance’ ‘Bundhu Boys’, not to mention several other new and emerging acts. And where there was coverage of the rock giants, then so be it – it was but one part.

They were very different programs. The Tube was connecting into a kind of younger culture vibe. Whistle Test, for all our changes, was still making shows for music and viewed by rock music enthusiasts. I’m not being disparaging to The Tube here, but we were trying to bring a level – a kind of journalistic level – to what we were doing, which made the philosophy of the two shows different.

David G. Croft

As for hip-hop and dance, perhaps the argument was that a different show could cater to this, rather than relying on Whistle Test. And indeed, a new televisual strand was on the way – DEF II – which incorporated shows like Snub TV and Dance Energy.

So, did the lopping of ‘Old and ‘Grey’ and the wider rebrand work? On a surface level, it was bold, brave, and moved the show on. Taking an established format and nudging it is highly risky. It clearly had some merit, particularly in the positive audience reaction, before EastEnders drove it further and further into the abyss.

Looking back as a viewer and as a ‘wannabe’ television archaeologist, it is also incredibly exciting. Compare the Spring 1983 series (the last as OGWT) and the live revamp of October 1984, and you can see the creativity involved in making such a leap.

However, it could be argued that losing the two words didn’t actually make much of a difference in the end.

In retrospect, my preference would have been for a refreshed Whistle Test to remain traditional late night fare, with Riverside continuing in it’s established early evening slot.

John Burrowes

Burrowes’ comment about two different shows catering to two different audiences made me think that a ‘new look’ can make a difference to the audience and critical perception. However, if the forces at play are greater, it’s ultimately a short-term fix.

In this sense, it wasn’t the rebrand that fast-tracked Whistle Test to the graveyard. It was more of a crossroads moment in its history, where the show could have retained its late-night slot, with another new show competing with The Tube, or it could have been moved earlier in the schedules to appeal to a larger audience. The latter decision had significant consequences, and, when aligned with institutional and industrial changes within broadcasting, there was very little that would have saved the series. Scheduling is a part of the identity of a series; it’s an expression of what audience a series is seeking. It can also make or break a series, given what else was on other channels during an era where we watched television as live, before on-demand, catch-up, and multi-platform. The time slot, rather than the revamp, was the death of the series.

In the case of Whistle Test, this was a real shame, because the rebrand didn’t lose sight of its core remit and its most essential attribute, which was getting eclectic, challenging, unique music seen on the television screen.

Whistle Test did this, right up to the very end.

Reflecting on the contributions made by the production team for this article, I was struck by how Whistle Test was significant for many different reasons, from kickstarting a career trajectory to the determination to make the best show possible. Also, it reminded me of the personal stories and lifelong friendships that were made by being thrown together as a team, and how much everyone learned from each other.

When I was at grammar school, I was walking around with Frank Zappa albums under my arm. I used to watch Whistle Test. It was the show to watch and then we’d all get together at the little sweet shop the next day and talk about it. It combined two areas that I found just wondrous – television and rock music. And then, 14 years later, I’m sitting in the chair. It was amazing.

The bottom line for all of us was we wanted to make a great show. That’s the number one.

David G. Croft

(Courtesy of David G. Croft)

We knew we were lucky to be part of it, meeting some amazing musicians, making long standing friendships and having a laugh.

Karen Rosie

It was great fun and amazing what we got away with. You couldn’t make a lot of it up. Even when you cocked up, I don’t remember anyone getting angry. I had worked on Arena before that as a PA, and the unconventional atmosphere was pretty much the same. The focus was always on the programmes. TV is quite different now.

When it all comes together there is nothing better than directing live music.

May Miller

I remember one Executive Producer saying to me “If it ain’t broken, don’t fix it” which is a sentiment with which I strongly disagree. You need to adjust and modernise all the time, otherwise a show becomes stale. I’ve made a career out of breaking rules I was told couldn’t be broken – audiences don’t seem to want ‘more of the same’. They don’t know what they want until they see it but, in my experience, innovation almost always produces the most successful outcomes and executives don’t really know anything.

Dominic Brigstocke

I don’t remember ever enjoying it at the time. However, I am glad that I did it because it’s the kind of thing that stands you in good stead many years later.

David Hepworth

Then there are the specific recollections, such as this one from Karen Rosie, about an occasion following an appearance by The Smiths on Riverside, where she and two other members of the production team (Nicky Hegerty and Fiona Clark), who were at the time assistants to Mike Appleton, transferred the music from the television studio to the streets of London.

I bumped into Morrissey outside trying to get a cab. He was missing his beloved Manchester. Nicky, Fiona and I went to see them at Ronnie Scott’s later and sang along to all the songs. A journalist commented on it in their review – can’t remember if it was Sounds or NME or Melody Maker but one of them.

Karen Rosie

Or, how a small artefact holds happy memories of special times – in this case, Live Aid.

I still have my ‘All Areas’ backstage pass.

John Burrowes

Or how the lessons learned during Whistle Test, were put into practice later on.

(The Word) was the very first independent show I directed when I left the BBC in 1990. On the first show I did, we had a French punk band who performed a completely different song from that which we’d rehearsed – my training on Whistle Test meant that in the gallery we just laughed at their cheek and ‘busked’ the number.

Dominic Brigstocke

And two final recollections, one each from the two producers.

One is televisual.

I continued directing and producing a whole range of entertainment programmes, including the development of the Big Break game show – peak BBC1 Saturday evening viewing with 15 million viewers – somewhat different to 1.5 million on BBC2 with Whistle Test and Riverside.

John Burrowes

And one is musical.

I think the best moment for me is Clive Gregson and his band, with Christine Collister and Richard Thompson doing Open Fire, and they’re playing these guitar solos against each other. It was absolutely fascinating. I think it’s one of my favorite bits of television.

Trevor Dann

We finish our story, where we began, in the ‘Comfy Area’ of the revamped (and not universally loved) BBC Breakfast Time studio in late 1987. Mike Appleton and ‘Whispering’ Bob Harris dropped in to reminisce before the show was put to bed.

All the old stories were dusted down – the Macon Picnic and Jimmy Carter, getting Bruce Springsteen, and of course, the meaning of the show’s title. Even the Breakfast Time presenter of the piece was given a coveted Starkicker badge.

But the moment that stood out to me was when Mike Appleton acknowledged that some people felt OGWT was too serious and po-faced. And then casually brushed it aside with the aside…

“But we didn’t believe that.”

Having spent a year researching how OGWT became Whistle Test, I’m inclined to agree with him.

Acknowledgements and references.

Firstly, I am very grateful for the time and recollections from:

Rosemary Barratt (Ro Newton),

Dominic Brigstocke,

John Burrowes,

David G. Croft,

Trevor Dann,

David Hepworth,

May Miller,

Karen Rosie.

I am also grateful for the archival assistance from Graham Hammond and ‘ScottishTeeVee’

Sources

Popular Music And Television In Britain By Dr Ian Inglis · 2016 Taylor and Francis.

Rock & Pop on British TV By Jeff Evans · 2017 Omnibus Press.

The Story of Light Entertainment Part 5 Pop and Easy Listening (BBC, 2009)

Graphic Design for Television. Merritt, Douglas. Published by Taylor & Francis Group, 1993

Music and Media magazine.

https://twitter.com/doctorwho1980s on Twitter. https://twitter.com/doctorwho1980s/status/1722554628703990085https://twitter.com/doctorwho1980s/status/1722554628703990085

https://theartsdesk.com/new-music/theartsdesk-qa-musician-jim-reid-jesus-and-mary-chain

The Making of Live Aid – A Conversation With David G. Croft, Kathryn Edmonds & Charlie MacCormack www. youtube.com/watch?v=juiSm3txPxk (2021)

Photos from Mark Ellen

https://rockstarsstolemylife-blog.tumblr.com/post/101161164785/whistle-test-on-set-3-andy-kershaw-talking-to

https://rockstarsstolemylife-blog.tumblr.com/image/83703824055

https://thequietus.com/articles/07301-jesus-and-mary-chain-psychocandy

www. youtube.com/watch?v=L5x4qnmiBUQ&t=148s (Forgotten Television Drama Youtube channel)

Neil Miles https://www.youtube.com/@NeilMiles

https://theartsdesk.com/new-music/10-questions-bobby-gillespie-primal-scream

https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/glastonbury-festival-tv-coverage

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2004/nov/19/realitytv.broadcasting

Record-Business-1982-04-12 – Riverside review.

https://www.muzines.co.uk/articles/smoke/11364

https://extensor.co.uk/articles/int_dann/interview_trevor_dann.html

https://www.flickr.com/photos/nothingelseon/albums/72177720296544060/with/51903053677

http://tech-ops.co.uk/pipermail/tech1_tech-ops.co.uk/2021-December/012950.html

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p055qk75 – Why it’s pointless trying to interview Bob Dylan!

Word in Your Ear – youtube.com/watch?v=uv5qay5vcp8

nostalgiacentral.com/television/tv-by-decade/tv-shows-1980s/oxford-road-show-the/

https://transdiffusion.org/2001/09/01/presentation

https://whatsheonaboutnow.blogspot.com/2020/04/if-not-for-whistle-test-and-mike.html

BBC DVD The Old Grey Whistle Test – Mike Appleton DVD commentary

BBC documentary – Live Aid. Against All Odds (BBC, 2005)

psgigs.wikispaces.com

MUSIC WEEK – 31 Jan 1987

Billboard 20/6/87

The Old Grey Whistle Test Quiz Book Paperback – 20 Sept. 2012 Mark Paytress.

Leave a comment