This is the Whistle Test office – a penthouse at the top of a now demolished 1950s office block, overlooking the front of Television Centre.

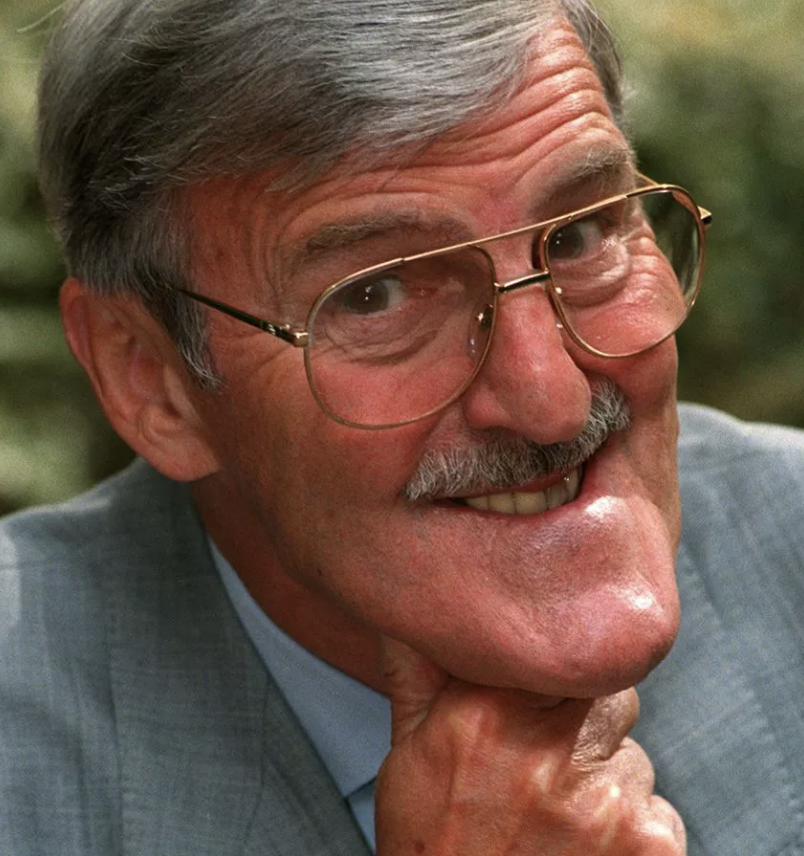

It was in a building called Centre House. He (Bill Cotton) had that office and then that had all been closed down. Mike Appleton – good man – had managed to move us all in there.

It was the most brilliant office (laughs) – beautiful views of the Westway. But it was a nice light airy kind of non-Television Centre office. It was not a rabbit hutch.

It was a good place and it was a creative place.

Trevor Dann

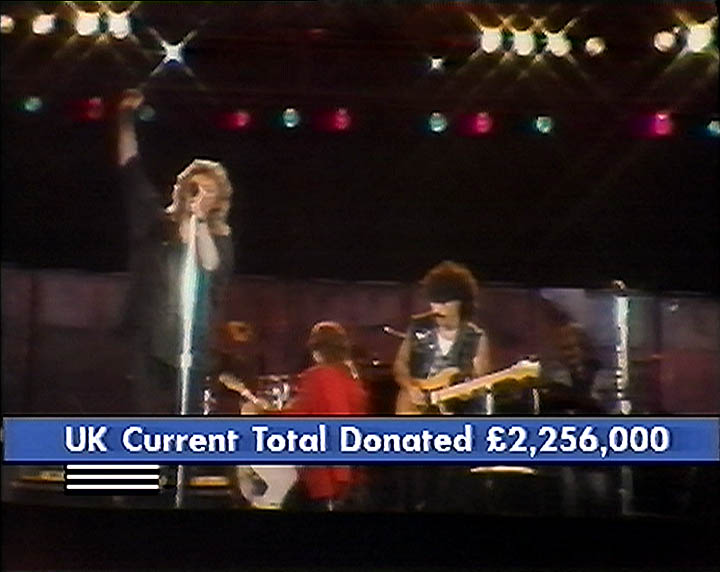

Arguably, the peak of this creativity would have been in May 1985 – into the last month of the 1984-85 series – when the Whistle Test team were responsible for the BBC’s coverage of Live Aid.

However, for a moment, let’s go back in time, half a year – to late 1984.

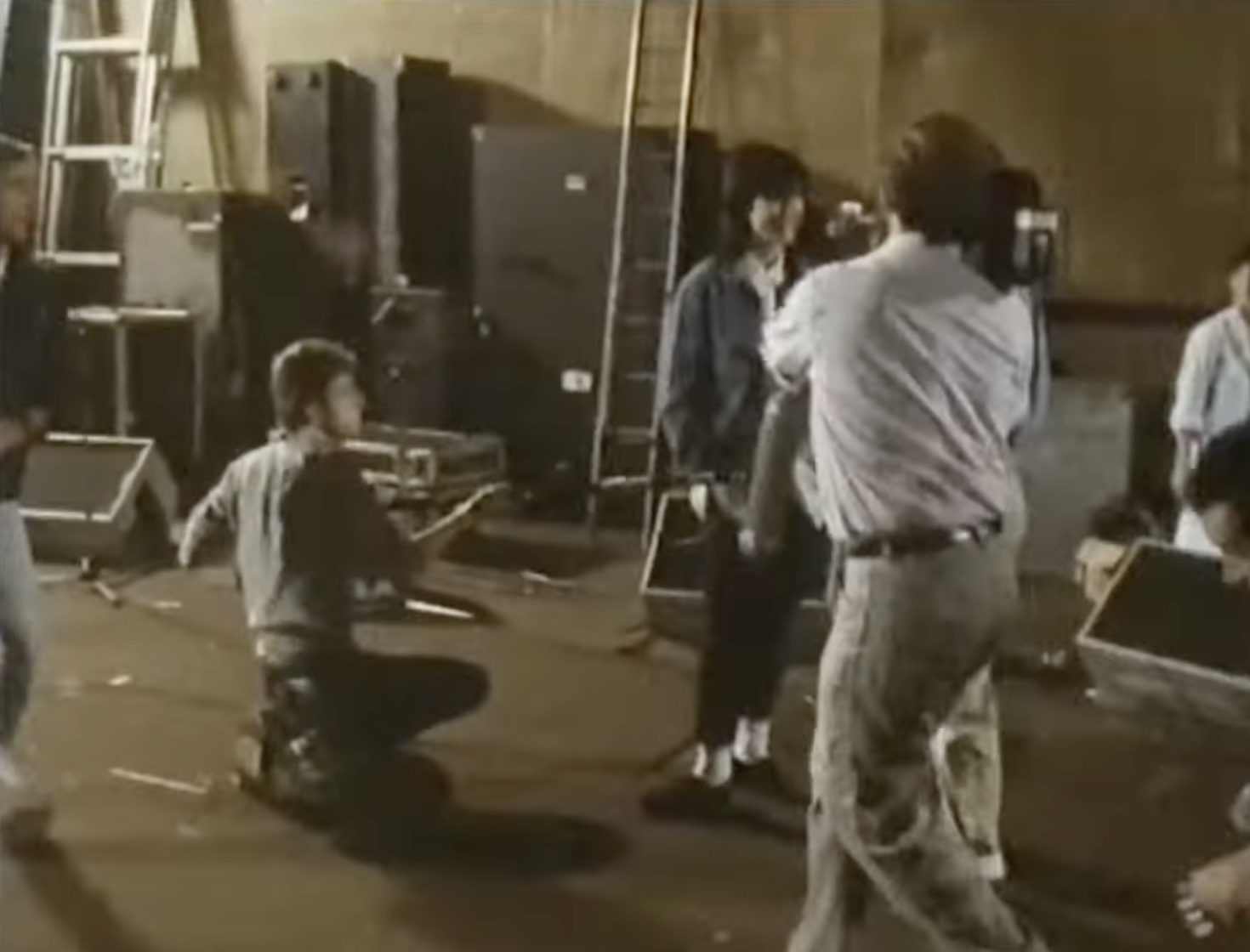

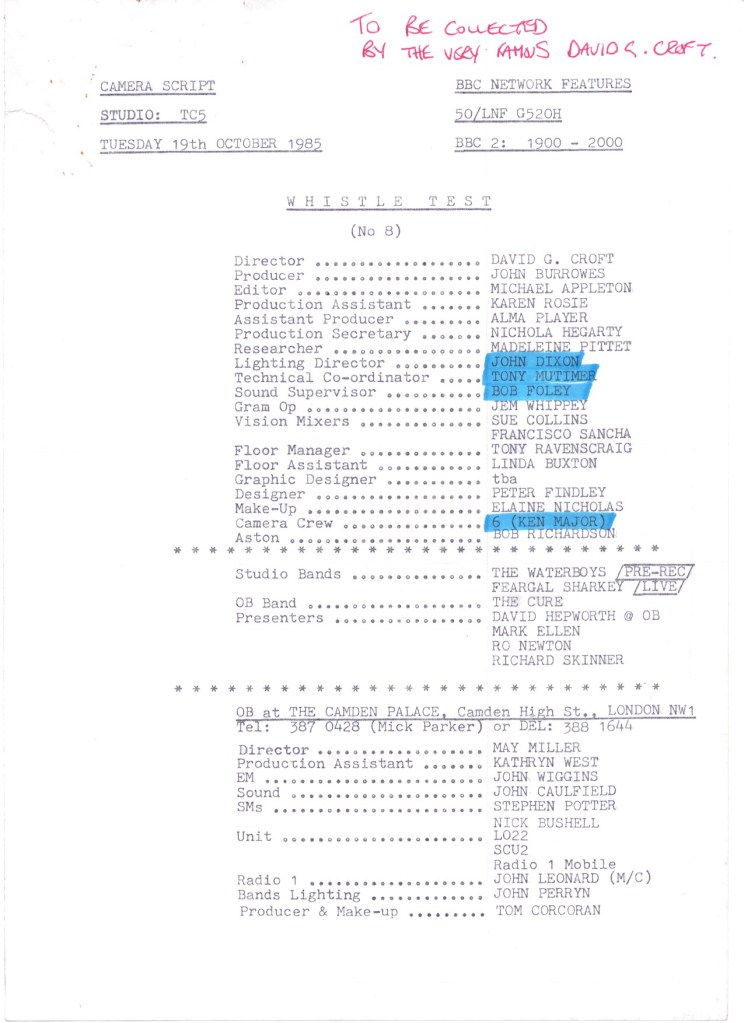

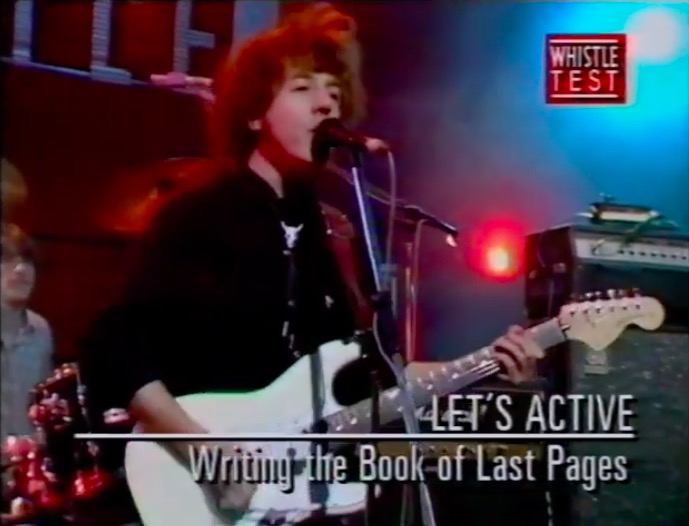

I had a phone call from Bob Geldof asking me to cover the Band Aid recording for transmission on Whistle Test. I decided to take a risk on his promise of famous names, and booked a crew with David G. Croft directing. The item was turned around and included in that weeks edition.

John Burrowes

The recording of Do They Know It’s Christmas? took place on a Sunday, meaning that the Whistle Test team had 48 hours to turn the item around. Mark Ellen can be glimpsed in the report, with David Hepworth assigned interviewing duties.

I was at the filming of the recording of ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas’ single in 1984. David G. Croft and I went along with a crew. There was an amazing amount of famous faces, all pretty much being humble and some offering to make tea.

Karen Rosie

Mind you, the turnaround time for staging a trans-Atlantic event in London and Philadelphia was pretty keen too. And it would be a challenge that would stretch the Whistle Test unit to the limit.

We didn’t know whether we were covering an event, or participating in it.The thing you have to remember about Whistle Test, was that we were a very humble little programme. We were 40 minutes once a week, occasionally, on BBC2. And here we were doing one of the biggest shows the BBC had ever done. It was like asking BBC Radio Cleckheaton to do the Olympic Games. You know, we really weren’t up to it.

Trevor Dann (Live Aid. Against all odds.)

The first meeting I went to, really there was only half a dozen people there. It was the WT team, Mike Appleton, and maybe a couple of other people.The third meeting, you could barely get into the room. There were all sorts of other departments involved.

David G. Croft (The Making of Live Aid, 2021.)

Behind the scenes, the production team were up against it. Even the ‘Comfy Area’ sofas made their way into the sweltering ‘Jimmy Hill Commentary Box’ – the glass-panelled observation platform located high up towards the roof of Wembley Stadium.

It was live television by the seat of its pants.

Mark Ellen (Live Aid. Against all odds.)

Absolutely no preparation, and absolutely no rehearsal at all.

In separate Live Aid documentaries, Mark Ellen and Andy Kershaw both stared into the abyss. Ellen recalled that he didn’t sleep and received an early morning phone call from Andy Kershaw, asking him if he had his brown trousers on.

Andy Kershaw (Live Aid. Against all odds.)

I remember being absolutely sick with fear, waiting for the BBC car to pick me up. And the car had already picked up Mark Ellen. And even Mark’s relentless joshing and wonderful sense of humour in the car up to Wembley couldn’t really make me lighten up.

The story of broadcasting Live Aid is fascinating in many ways. On one hand, there is the culture clash between staging a concert and broadcasting an event. Bob Geldof himself noted that the BBC’s level of military planning came straight from wartime strategy. Others involved in setting up the Wembley concert recognised a feeling of relief when the cameras were installed. and timings identified.

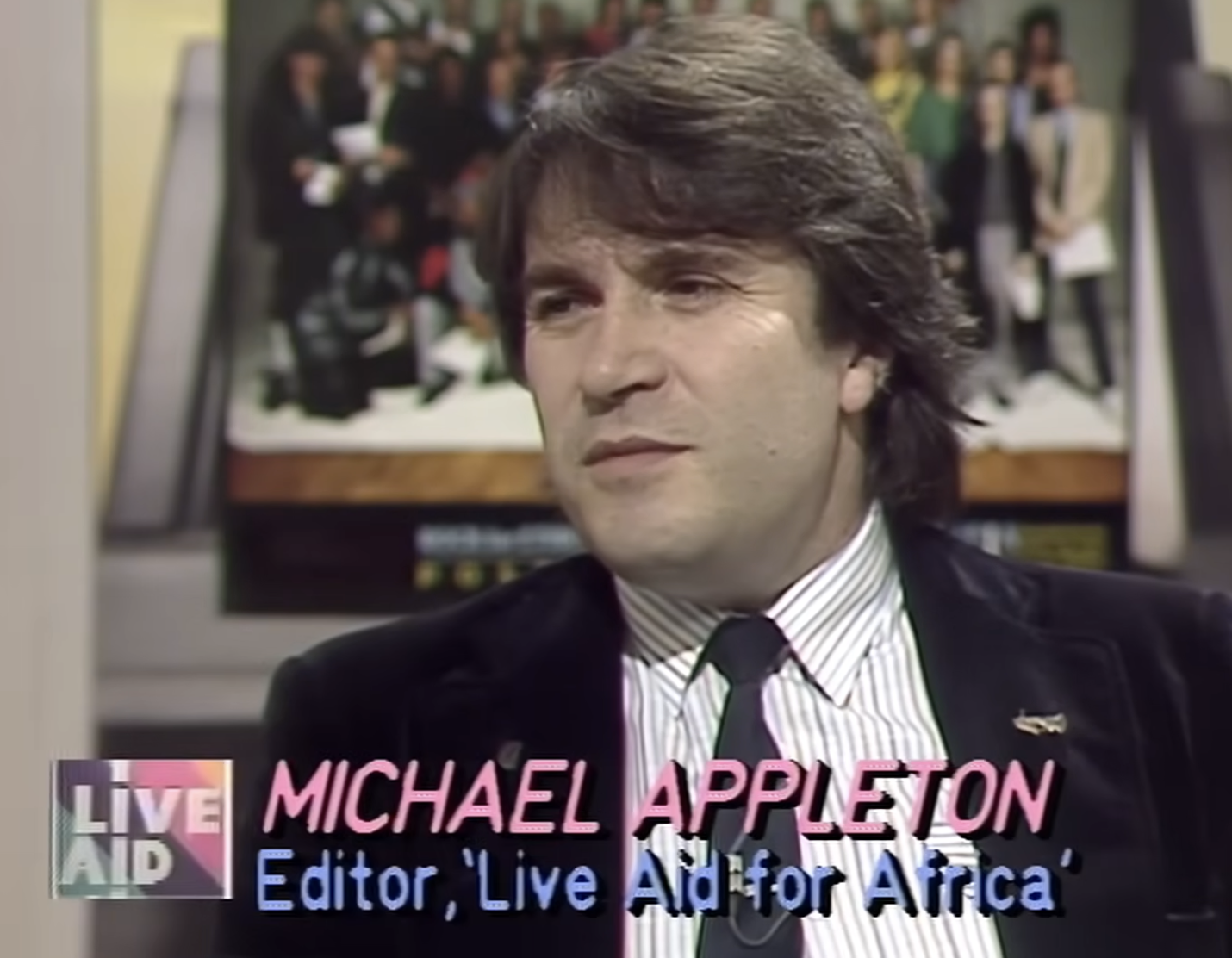

On another level, there was the logistics. Mike Appleton noted a 9-camera set-up at Wembley (including two cameras on a blimp). Additionally, a three-camera setup was used for the nightclub after-party, and a single camera was used at Heathrow. It’s interesting to note that when Appleton was interviewed by Noel Edmonds for the preview show, his concerns were about what was to come, rather than what was already encountered – linking with Philadelphia was going to be a nightmare.

And then there’s the sense of keeping it together, no matter what the surprise. Richard Skinner experienced this when he announced, “It’s 12 noon in London, 7am in Philadelphia, and around the world it’s time for Live Aid!” Only, he hadn’t banked on his words not only being broadcast, but amplified through the PA in Wembley Stadium itself.

The three directors, Tom Corcoran, myself and John D. Smith…worked out who was going to direct what. Tom wanted to direct the finale. And John D.Smith wanted to directe the opening. So we all knew what we were doing.Karen Rosie […] gave me a tape and said, “Alright, David, these are the tracks.” But, of course, we didn’t hear them play the live versions, did we? So, all I could do was listen to the version on the albums.

[…] there was no rehearsal. The directors had no rehearsals with the bands. We didn’t get told what the line up would be!

David G. Croft (The Making of Live Aid, 2021.)

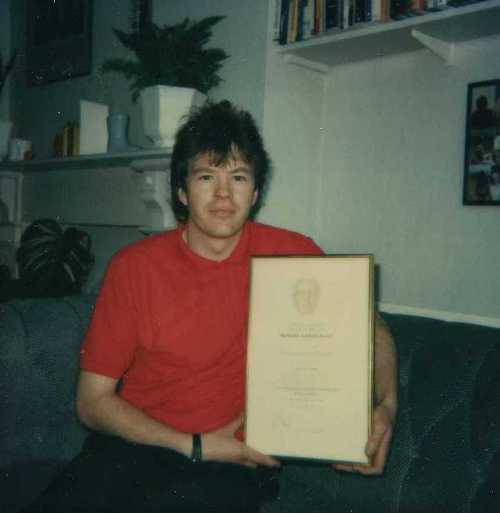

The herculean task passed off successfully, bar a few technical glitches, the f-bomb, and an unavoidable lack of preparation, which will have been unremarkable to the television audience, but no doubt felt acutely by cast and crew. Mike Appleton and the Whistle Test unit secured a BAFTA, and there will have been confidence within the production team.

Plenty has been written about Live Aid over the years, and this blog post is about the Whistle Test series specifically, so we will recognise that important event briefly, but not underestimate its significance.

(Courtesy David G. Croft.)

I also think that Live Aid changed the relationship between the broadcaster and the viewers, in that it was the first ‘interactive’ programme to take place on that scale. By ‘interactive’, I mean that it asked the viewer to do something – in this case ring in to make a donation, or go to the bank.

In this sense, it was the forerunner to pressing the red button today. Before this, broadcasting and viewing were discrete events – broadcasters broadcasted and viewers viewed.

Trevor Dann (Live Aid. Against all odds.)

David G. Croft (The Making of Live Aid, 2021.)

“And then course, it would have been back to work on a Monday, wouldn’t it? Back to the day job!”

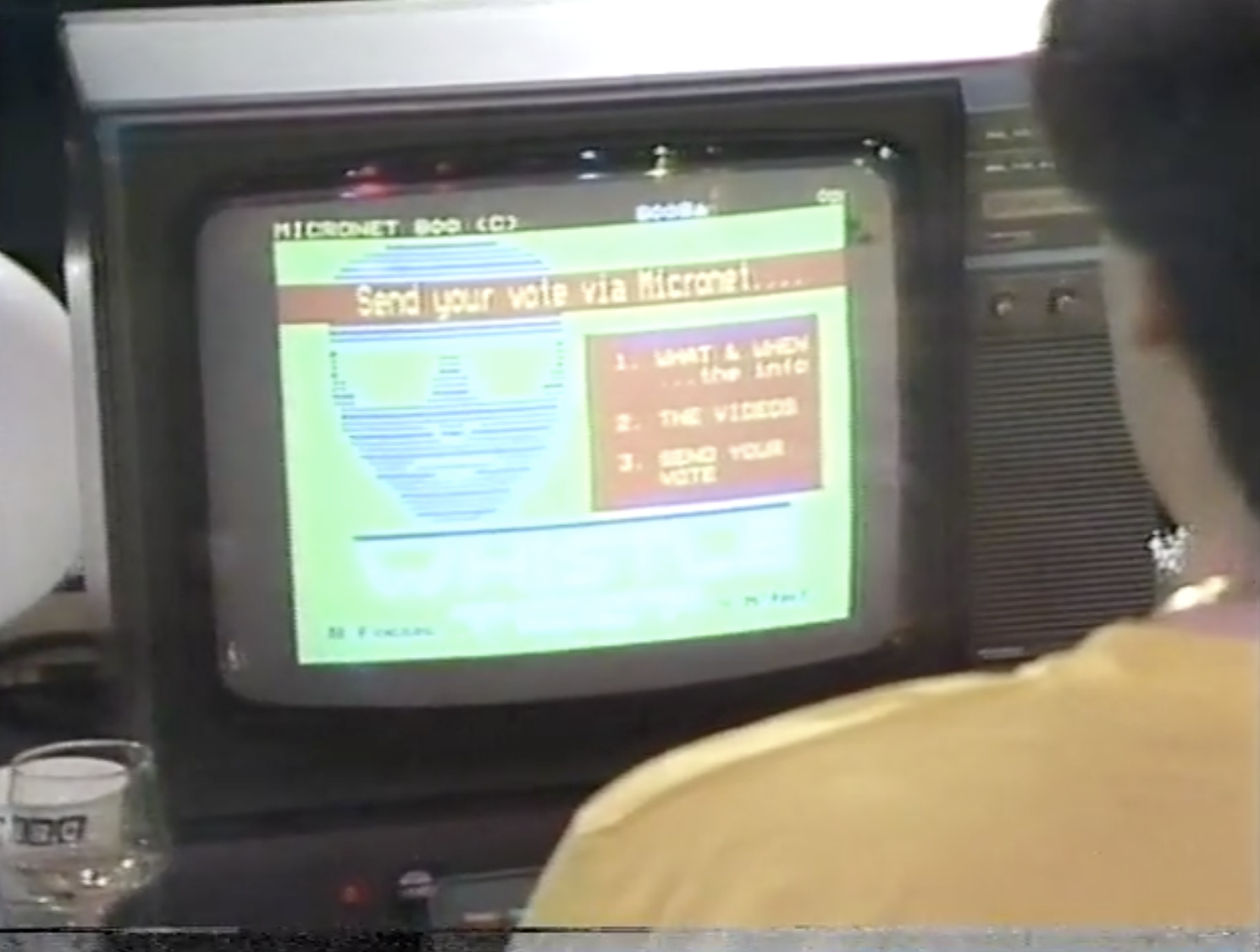

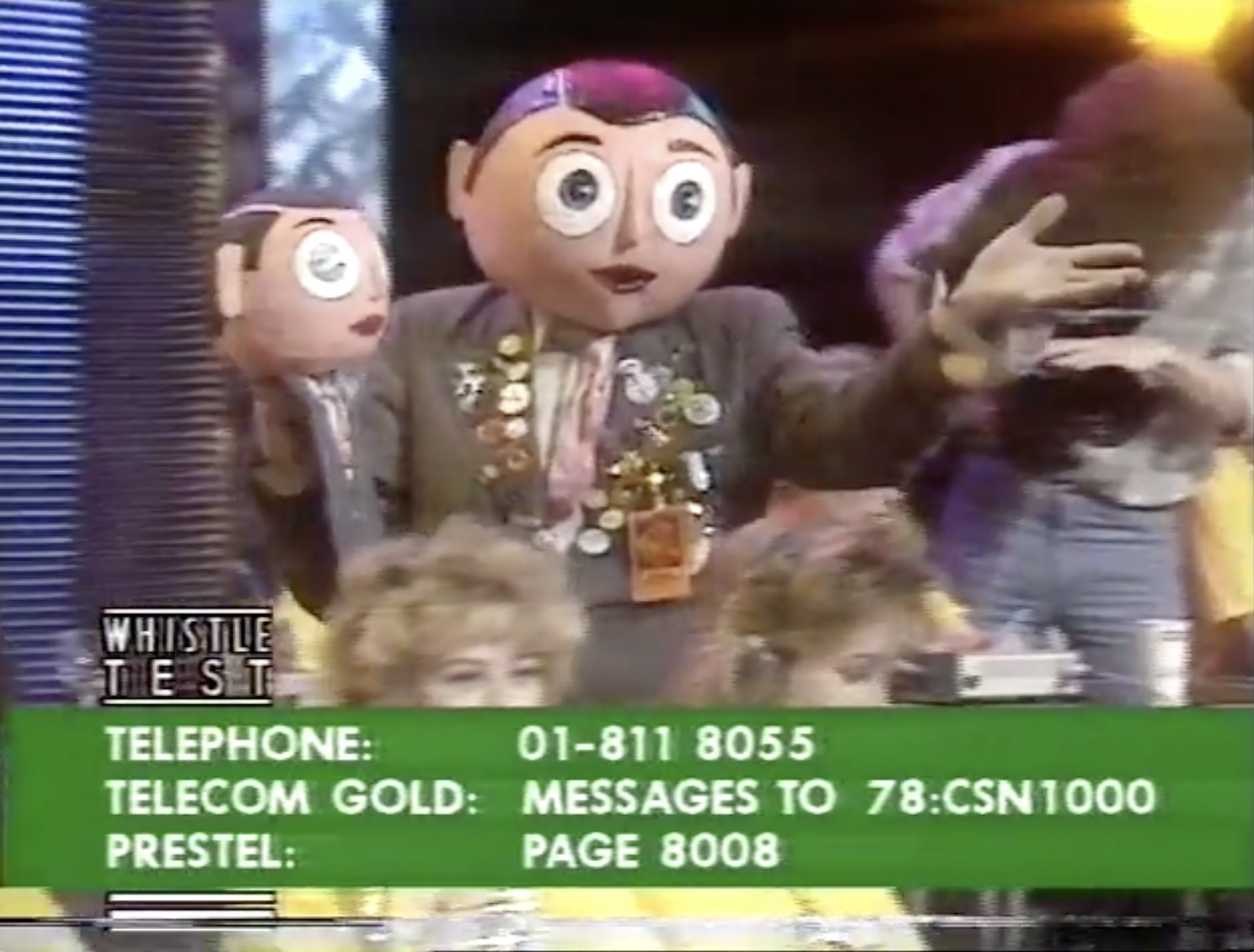

Back at Television Centre, interaction was a key feature of the revamped Whistle Test, with the live show offering increased audience participation. An example was the ‘Video Vote’ – the concept of which was very simple: a selection of promotional videos would be teased, alongside the familiar BBC telephone number – 01 (if you’re outside London) 811 8055. The winner would be played in full at the end of the show.

The first Whistle Test show following Live Aid is a good example of a typical selection:

- Talking Heads “Road to Nowhere”. (This was the winner.)

- Cabaret Voltaire “I Want You”

- Jesus & Mary Chain “Just Like Honey”

- Guadalcanal Diary “Watusi Rodeo”

All very straightforward, but the sense of interaction and immediacy further cemented the very close relationship between the show and its core audience. The vote would also be a key component of the New Year’s Eve ‘Pick of the Year’ – which would move beyond a selection of four choices, towards Eurovision heights of delight!

As an interesting side note, several Whistle Test contributors recall how Tom Corcoran had a natural affinity with a communication mode that we take for granted today.

Tom was an engineer and very much into computers early.

Karen Rosie

He was the first person I knew who understood email, and he had one of these acoustic coupling devices so, if you were in America, or if you wanted to get in touch with somebody in America, you put this acoustic coupler on these two pads, and you put in some dodgy code or whatever, and suddenly you’d be talking to the manager of The Smiths in Les Vegas. He was very bright, very inventive and he used to build bits of electronic gadgetry and stuff.

Trevor Dann

Tom had discovered the internet and email, which in 1985 was very progressive. He’d used a BBC micro and connected his office phone handset, pushing it into a modem (like in Ferris Bueller, as you had to do in those days) and send simple one-line messages all over the world. It was very crude, but worked. I think everyone thought this was bonkers, but we loved Tom and his funny ways, so it was never mocked.

Dominic Brigstocke

A feature during the New Year’s Eve special, included Frank Sidebottom, extolling the virtues of email, to enhance the video vote.

FRANK SIDEBOTTOM: Popstars use this, you know, like Madness and The Thompson Twins.

The NME article ‘Old, Grey, us??’, towards the end of the first live series in May 1985 (see part 3 of this retrospective), noted that few stylistic changes were being planned any time soon. However, it is rare for the fast-paced world of television production to sit still. So, when Whistle Test returned on Tuesday 1st October, the format was unchanged, scheduled within the 7.00pm timeslot on a Tuesday. Perhaps the EastEnders sized dent in the audience wasn’t too much of a concern at this point.

However, in terms of presentation, there were subtle tinkerings and bold new approaches. The subtle tinkering involved a perfectly good title sequence where the flash of light through the Venetian blinds and the reveal of the title, were replaced – for no good reason – by a slowing down of the final shot and a clunky video inlay of the title caption.

More significant was a change in studio set design. On one hand, the Comfy Area had a refit, losing its curios and art deco sensibilities. Replacing it was a marbled, layered, somewhat postmodern sensibility, commonplace in 1980s design at the time – TV-AM headquarters was a case in point.

This was mirrored in the performance area, which no longer looked like a concert stage, but more like a true representation of 1980s design sensibilities, with a large Venetian blind emblazoned with the words ‘WHISTLE TEST’, set within a classically inspired but distinctly 1980s temple facade. Around this time The Tube also moved towards classical motifs in their set design.

Whistle Test was firmly referencing the tastes of the time, a far cry from the bare-walled studios of old.

Following a prior attachment in early 1985, Dominic Brigstocke rejoined the Whistle Test production team. Now a noted producer/director, with a CV that includes everything from Knowing Me, Knowing You with Alan Partridge to Horrible Histories, the attachment to the Whistle Test unit was the very beginning of his television career, and a profound one at that.

I was actually a production trainee (as was David G. Croft before) and so was placed on programmes to get experience. At the end of two years ‘training’ (and I use that term loosely as there wasn’t much actual training – it was more, throw them in and see if they float), you were expected to apply for a job. If you failed to get a job, you were out, though that was rare.

I wasn’t pleased to be put on Whistle Test – I wanted to make documentaries, but on just my second day at Whistle Test, we did a show which David directed. I was completely blown away by how exciting live multi-camera music television was. My palms were sweating and I couldn’t believe how clever it all was – the shot calling, the split second timing and precision of the inserts, counting the seconds on and off the air, and the cutting together of the music.

I completely fell for studio directing in that moment and, as a direct result, have spent much of the last forty years in television studios doing multi-camera comedy and music.

Dominic Brigstocke

It would appear the training extended to all facets of public life.

I was not really prepared for the experience – I remember going to a Ramones concert wearing a thick Alpaca Herringbone coat and carrying a briefcase! Fortunately, I stood at the back and no one took much notice of me…

Dominic Brigstocke

Back at the BBC, the learning curve was steep, but the rewards were reaped quickly.

I was made aware very quickly that I would need to generate my own ideas, and that’s the way I would get opportunities. David G. Croft could not have been more supportive. He involved me in what he was doing, which at the time was a feature about rock photographers – I learnt where the rostrum camera was and how to edit videotape.

I was astonished that someone as young as he appeared to be (he was actually 30ish) was directing live TV. As it happened, I was directing live TV within four years and prime time Saturday night entertainment (aged 29) within five – that’s how it worked in those days. David encouraged me and gave me opportunities to direct pre-recorded bands and bits of films and then, quite soon, I was sent out to make films on my own, which was terrifying!!!

But I loved it, and after six months I had to move on to another placement, but I came back to work on Live Aid and then did another attachment the following year.

Dominic Brigstocke

And experience led to bigger breaks over the next few years.

I was mostly a dogsbody, but made films, directed inserts, listened to all the records which were sent in, organised and liaised with record companies, etc. etc.

With that experience, I was able to come up with ideas for films and if I could persuade the producer, I was sent out to make them. Northern Soul and Welsh Language Bands, as well as The Housemartins, were my best efforts.

My 1987 film about fans going to see Deep Purple in Paris was an unmitigated disaster. But just as often, I was sent out to do something the producers wanted; Frankie Goes To Hollywood merchandise, cassette piracy, etc.

Dominic Brigstocke

It’s interesting to get a sense of the determination to book the right acts for a Whistle Test. It would also appear that it could be a labour-intensive process.

On one occasion, we were sent a tape by a singer who appeared to be an old man writing songs on a keyboard. I listened to it and it was really unusually good compared to what was mostly sent in. Trevor agreed and I phoned him to invite him on the show, and he sounded quite surprised . But, it turned out to be “John Shuttleworth”, launching his career, and we never did get him on – we should have!

Dominic Brigstocke

With one full live series behind them, the presenting team had established a distinctive presenting style, largely irreverent and off-the-cuff. In many ways, it was a further evolution from the OGWT of old, with the Richard Williams/Bob Harris brand of reverent (and softly spoken) delivery, giving way to Nightingale’s more humorous slant in the face of punk.

The biggest change that took place in my time on Whistle Test concerned the autocue. When I started, they had one, which was operated by an outside contractor, and that was used mostly by Annie Nightingale. When Mark came on board they ditched both autocue and operator. Mark and I (and subsequently Andy) would write our links on cue cards, which were held up by the floor manager. Some of our links were so baroque that they were reffered to as “Three Carders”. I don’t think our words would be in the script which the production staff saw.

David Hepworth

Hepworth also notes that TV presenting came second to their role as journalists, which might explain the tendency to send things up. Indeed, in-jokes were the order of the day. Richard Skinner was often introduced as “The man they call...” David Hepworth was cuddly, Mark Ellen was yummy, and Andy Kershaw? Well, he appeared to – more often than not – dish out the one-liners than take them.

While there was a distinct sense of camaraderie between Hepworth, Ellen, Skinner and Kershaw, it was very different to the anarchic tone of The Tube.

What is a big difference between The Tube and Whistle Test? It’s the attitude of the presenters towards television presenting. The Tube were wild, wacky, they broke the fourth wall, they were young and trendy. Good. It’s got a live audience in the studio.

As far as I’m concerned, that’s where it ends. We’ve got David and Mark we’ve got Andy Kershaw, these guys knew their stuff.

I think those shows could, and did, exist in the same world together.

David G. Croft

We were driven not by fashion but journalism; by substance not style. We were impressed by what we thought was good music deserving of a wider audience or a good story about a band, even if they happened to be terrible, told well.

Andy Kershaw (No Off Switch)

And, maintaining the tradition of OGWT, the presenters were able to use their journalistic credentials to share their own opinions of the acts featured in that week’s edition – especially for those in the audience who could read between the lines.

Dave and I were magazine editors and used to the idea of presenting music we didn’t personally adore. If we liked stuff, we enthused; if we didn’t, we might drop the odd hint. “Sting there with his new single “Russians”, Dave announced. “They should never have given that man a library ticket.“

But Andy was mortified if he had to introduce anyone that wasn’t dead-centre of his universe, in fact refused point-blank even to be on a show that featured the glutinous bed-wetters Tears For Fears. Viewers were in no doubt as to his personal taste – boyish joy for his favourites, amusing sarcasm for everything else.

Mark Ellen (quoted in Rock Stars Stole My Life!)

We were never deferential to rock stardom and I was predisposed to be deeply suspicious of it.

Or prehaps, it was a front, masking the terrors of live television!

Andy Kershaw (No Off Switch)

A neat example of both nerves and irreverence was the opening link by Andy Kershaw during the first edition of the Autumn 1985 series of Whistle Test. Following another reminder that the show was no longer ‘Old’ or ‘Grey’, Kershaw expressed his excitement for introducing The Long Ryders, by acknowledging that he completely fluffed his lines introducing them during the series before, and then throwing a ‘complete wobbler’ at the camera, at which point Mark Ellen took over.

…in Mark Ellen, particularly, I found my television soul mate, someone boyishly funny who found the interaction of the ludicrous worlds of the music industry and television endlessly amusing.

Andy Kershaw (No Off Switch)

It was always nerve wracking, because that’s how all telly was in those days. You were the frail human face of it all. You always felt that anything that went wrong was your fault.

David Hepworth

With the producers remaining conscious of the audience, it was time for a changing of the presentational guard – a decision that had been considered a year earlier.

Mark looked a lot younger than Dave but the two of them together just said ‘rock’ in an old-fashioned way. Initially, the plan had been to try to move Dave on and bring in somebody new with Mark but then it was felt that, actually, having three might be better.”

Trevor Dann, (quoted in Rock & Pop on British TV)

David Hepworth had been a part of OGWT/Whistle Test since 1981.

Oh, it was the usual ‘You’ll do more filmed items’ sidelining. By that time they had more presenters than they had slots for and I was the oldest member so I had to go.

David Hepworth

Mind you, the sidelining included some plum jobs – Springsteen, Jagger et al.

(Courtesy David G. Croft)

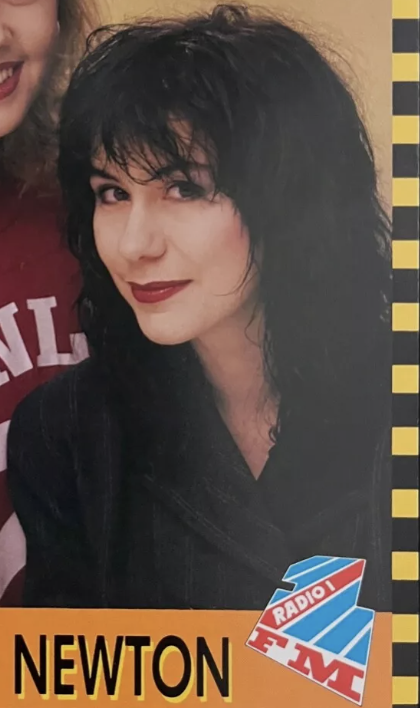

Including Hepworth, there were now five regular presenters. Joining the ranks of Whistle Test, from this series onwards, was Ro Newton. It could be argued that a female presence on the show was needed (Kershaw notes that if he hadn’t been selected, a female presenter was likely to be hired.)

Ro joined because it was clear that having a team of entirely white (mostly middle aged) men was no longer acceptable, as society was changing. And Paula Yates was making a big impact on The Tube.

Dominic Brigstocke

Newton left school in Stockport in 1983 with the desire to be a music journalist. This led to a place on the Periodical Journalism course at The London College of Printing in Elephant and Castle. Following a year in the capital, Newton returned to Stockport, and thanks to a phone box across the road from her parents’ house, and a limited supply of 10p pieces, got in touch with her future husband John Barratt, who at the time was a local band manager, and supported Newton’s ambition to write about bands in the area.

I was the first person to write about The Stone Roses, getting a live review published of their gig in Preston. I actually travelled in the van with the band, almost falling out. At the gig a fight broke out between the band members and audience. I remember Mani was involved before he even joined the band. John’s music connections opened doors for me. I remember when I was learning to drive, taking a trip to Leicester with my Dad in his car to do one of the first interviews and reviews for Simply Red who were tipped for big things.

Ro Newton

A spot of volunteering on Piccadilly Radio in Manchester, working on the late-night alternative radio show, was followed by a scholarship to the National Broadcasting School in Soho for a course in radio presentation and production. This would serve Newton well, and eventually, she would be heard on Radio 1, including a Sunday afternoon pop magazine programme called Backchat, devised alongside Newton’s friend Liz Kershaw, Andy’s sister.

I was already contributing to music publications from home. I remember very vividly interviewing Morten Harkett from A-ha in the phone box at my local station. I’d give the number to the press officer and then have to wait outside the box for ages until they rang! Then I’d have to try and disguise the sound of trains going through the station!! It was all very much of a learning curve. I had already been trying to get my foot in the door as a freelancer at EMAP (Smash Hits and Just 17) before I got the Whistle Test gig. Then when I met Mark Ellen, he very kindly opened the door and I spent many years working there as a freelance contributor.

Ro Newton

It is clear that Newton was starting to make inroads into radio and journalism – a classic pre-requisite if you’re ever going to make it onto Whistle Test. However, television came calling.

I’m not sure why I decided on this change to my path, but I knew I wanted to do something in the media. I was a big fan of The Tube and loved Paula Yates and Muriel Grey. That was my dream to work on! I found out that The Old Grey Whistle Test wanted a new female presenter.

Ro Newton

And it wasn’t long before Newton was up against some formidable competition during the audition.

I remember going for the audition and I had to interview musician Andy White. At the time I looked quite gothy with black spiky hair and the black leather jacket was ‘de rigeur’!! I think they wanted someone with a northern accent to complement Rochdale lad Andy Kershaw, who had established himself very well on the programme.

Ro Newton

At that time we auditioned Mariella Frostrup. I’ve made some mistakes in my career – I’m the guy who said West End Girls by the Pet Shop Boys would never be a hit so I stand by my track record of abject failure. But, I said I didn’t want her on because I thought she looked too old on screen.

By then it was absolutely clear that the show was being presented by people from the British Legion of rock and we needed somebody who who didn’t even know Ry Cooder was.

Ro made the show look a bit different and with telly you know it’s half the battle isn’t it?

Trevor Dann

I think I was gobsmacked to get the job. I probably went in there with the thought that I’m never going to get it so I didn’t let the nerves get a hold of me. Then the reality hit hard!!

Ro Newton

That reality of live television was a pleasure deferred, given that Newton was introduced to viewers as a pre-recorded film insert during the first edition of the new series on 1st October 1985. However, even a filmed report had its challenges.

I think my first job was a filmed insert with Midge Ure. I must’ve looked and acted very green but he obviously picked up on that. I remember having to chat to him casually as we were walking along to the rehearsal space and it didn’t feel particularly relaxed. There was also an interview conducted with him. The band were playing in this great aircraft hanger of a place and I instantly remember being so excited because Mick Ronson was playing guitar. I couldn’t wait to tell John (Barratt) because he was a massive Bowie and Mick Ronson fan.

Ro Newton

It wasn’t long after Live Aid and I think Midge was riding on a wave of success. He definitely had the air of someone who was full of his own importance. Perhaps he didn’t like that WT had sent their rookie reporter to interview him!! He went through the motions, but I definitely didn’t feel that he warmed to me. Perhaps he knew that I was a fan of Ultravox when John Foxx was at the helm!! I think it was at the end of the filming when he took me aside and said something cautionary along the lines of “You shouldn’t think that other people you interview (ie rockstars) will be as easy going as I’ve been.”

Ro Newton

Fortunately, subsequent interviews were less intimidating.

I was sent over to the Hammersmith Odeon where Laurie Anderson was preparing for her show. She was a lot of fun and very warm and friendly. I remember she covered me in synth pads and proceeded to play me. I really enjoyed meeting her, although I was probably quaking again because she was such an icon.

I think it took me quite a while to build up my confidence, and when I watch those interviews back, I hardly recognise myself as I was so timid!!

Ro Newton

By all accounts, all the presenters got on well, and recognised their own diverse taste in music, itself an essential Whistle Test attribute.

I’d grown up loving alternative music and some of my favourite artists were Gary Numan, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Bauhaus, Depeche Mode, and lots of electronic bands.

Andy Kershaw was completely different to me though with regard to our musical tastes. I just remember that he and Trevor (Dann) were very closely aligned musically, loving all the American guitar bands, while my taste was more indie and close to home.

Ro Newton

It appears that this cooperation was extended to the production team.

I found all of them delightful to work with and very professional and kind to me. Even Andy, who knew that I knew nothing at all about music, was helpful and considerate. I can imagine that there was pressure to make the show younger and more modern as it was in danger of being cancelled.

Dominic Brigstoke

As we will discover later in this chapter, both cast and crew needed to learn quickly, both in terms of musical knowledge and television technique..

I can remember feeling very intimidated by my other presenters who were seasoned professionals, and being baffled by a lot of the ‘in’ jokes that they had going on. It did feel quite blokey – I was the token young female – and much of their musical references went straight over my head.

I remember being thrown in the deep end right from the start, and I can’t remember anyone really guiding me through the rigours of presenting on live television. I didn’t have that self confidence, self assurance and slick performance that oozed from the other presenters, or the quirky cocksure enthusiasm of the young Andy Kershaw who bucked that trend and made his own mark.

Early challenges were definitely reading from the autocue naturally, and trying my best not to look like a rabbit in the headlights. I don’t remember anyone really holding my hand through this process.

Ro Newton

Nonetheless, Newton did bring a new element to the series, providing a much-needed female presence and someone with a distinct visual look that cut through the established Whistle Test style. She also continued an important tradition of the Whistle Test presenter – she was knowledgeable about music.

Her status as de facto Whistle Test presenter must surely have been cemented once she was gifted her own ‘in-joke’, with Mark Ellen in particular, linking with the words “Ro Newton – Speak to your nation!“

The challenges faced by Ro Newton will be familiar to many people involved in the production of a weekly series. OGWT was famously created from pennies, from the lack of scenery to the ingenious ways of marrying up new album tracks to archival footage.

The Whistle Test of 1985 was a different proposition, but the challenge was the same. The budget had increased, but comparatively, the demands of output were greater – a live hourly broadcast, in a larger studio, with multiple presenters, bands, features, and videos. The show was limited by what it could do, given time and money.

(Photo – Mark Ellen – https://rockstarsstolemylife-blog.tumblr.com)

If the BBC were a studio factory, the limitations were part and parcel of television production, and a framework to push boundaries.

The studios and cameras were usually block booked in advance so directors worked within parameters, depending on guests, sometimes additional lighting and fx. Smoke/dry ice was requested if the budget allowed it.

Karen Rosie

For Dann, who came from a radio background, the move to a live series was not a concern, although it did highlight some of the challenges of working with television engineers.

For me, television was radio with pictures, so doing it live was of no consequence to me. I couldn’t understand why that would be any kind of problem because radio is live for the most part, but I never really settled.

I remember my first editing session with a guy we working with on some videos, and I would say “Right, can you come out at the end of the chorus, and we’ll go straight to the interview, okay?” And he’ go “What’s the chorus? What’s the shot?”

It was hard working with people who had a television mindset. It always felt to me as though the technology of television got in the way, and I think I didn’t make myself very popular by saying “Oh, we should just do it.”

Trevor Dann

Sometimes, the challenges imposed on Whistle Test were well out of the control of the production team. However, everyone had their eye on practical solutions – some of which could be described as quirky and ingenious.

We had to keep Whistle Test going during a strike. There are maybe three or four shows in a row where the set doesn’t look complete, because the set designers or the set shifters were on strike, so we couldn’t get our own set in, so we had to mix and match with various things.

I hope this isn’t apocryphal because it’s a story I’ve told many times. We once went into our studio which was empty except they’d left in the set for Tomorrow’s World, and it was pointed out that if we turned it around it said WT.

Trevor Dann

In keeping with studio practices of the time, a weekly show such as Whistle Test would have its set constructed overnight, in readiness for a day of rehearsal and transmission. It would be a long day. For the director of the show, it might be a case of beating the rush hour by arriving in the production office really early in the morning (The Jesus and Mary Chain – take note).

Although one band will have been pre-recorded, earlier on the day of transmission, studio director David G. Croft found the switch from directing the pre-recorded Whistle Test of early 1984 to the new live format highly exciting. There was no room for any mistakes and no chance for bands to opt for a take two. Planning how the band will be portrayed in terms of lighting, camera shots, and vision mixing will have been paramount, and will have lost the luxury of pick-up shots recorded later on. For the presenters, there was a shift into a more theatrical mode, where performances needed to be delivered first time.

When the show is pre-recorded, you can shoot the band and then you can go. “Stop recording everyone, marvelous! Right, cameras, let’s all move over to the next set.”

When you’re live you can’t do that. You’re thinking. “How do we move from the band to the interview area? Which cameras will I release?”

You approach the show in a more military style way, particularly in the way the studio floor is run. This also meant that the rehearsal process was much stricter, because we needed to be able to determine and confirm that moving from here to here is all going to work.

The plus side is it’s fantastically exciting, because you, the crew, the presenters and the performers – you’re all in the moment. What’s happening right now is what’s going out on television screens right now, and that is a massive adrenaline rush.

David G. Croft

Although Whistle Test will always have been dictated, to a degree, by band availability, the switch to a live format required a rigid structure. A whiteboard in the production office became the mecca for all planning.

The shows were fairly ad hoc and generally structured around band availability – the pluggers would come in and tell us when the bands wanted to play – this was mostly decided around album releases – so we had very little control over that.

A whiteboard was set up on one wall, divided with coloured tape into shows, each one a rectangle (this was actually standard across most tv shows in those days), and each section was filled in as it was booked.

So, there was a live band and a pre-recorded band (and later a Town and Country Club recording), and then a film item, a studio interview, etc. So, the structure was already set out and it was a matter of booking things in and pre-planning, so that you had films ready for the scheduled transmission dates.

This rigidity made planning simpler, but also meant that shows were formulaic, which is not necessarily very creative. Films were shot on literal film in those days and ‘telecined’ to tape for transmission. We had a serarate film cutting room, and after the films had been cut, they’d have to be sound mixed and a print made. Then the ‘inserts’, films and recorded items, were put together on a single piece of tape for playing into the studio the evening before the broadcast.

The day of braodcast was taken up with rehearsals in the studio (the set and lighting went in the night before) and pre-recordings and then transmission live at whatever time it was.

Dominic Brigstocke

Going live meant changes to the typical daily recording schedule. Whereas the previous, pre-recorded series (winter 1984) was sound-checked, recorded and edited over a single day in readiness for imminent transmission, the live series contained more content and once again featured two bands rather than one.

Some essential ingredients of the live broadcast would be constructed and prepared the day before.

They would do an overnight set. So we’d come in and…the set was up. Then once the show was over, they’d start taking the set down. It was the still in the 1980s when BBC Television Centre was this wonderful factory. So, there wasn’t the luxury of leaving sets up.

David G. Croft

The other ingredient was the pre-recorded content.

The day before the studio, I would, with my production assistant, go across to VT, and assemble all the video clips and films that we were going to play in. We’d put them on a one inch tape and we’d put them in order.

Back in the day, we would have to create what was known as the insert tape for the programme.

So, we go across in the afternoon and we go “Alright, what’s the first insert? It’s the clips for the video vote.” So, we put those together and…then “Here’s a film about Robert Smith” and then we’d put them in.

On the day of transmission we would go to VT again and we’d say “There’s the insert tape” and you’d have a VT editor in a suite there. They were in the basement and they’d be there ready.

Of course when you go live, I would say and “Run VT” and they press a button and there it was.

Then when that was over, they then spool the tape and park it ready for the next insert.

David G. Croft

The set-up and soundcheck for the first studio band (who would be pre-recorded and VT’ed into the live show) would take place in the morning. Once that performance was captured, the instruments would be taken apart, and the stage cleared, in readiness for studio rehearsals.

We would have started rehearsals at around 10:00am – rehearsing with the first band. Maybe at 11:00am we would have recorded the one track that the band were going to perform on the show.

David G. Croft.

These were big shows, requiring a lot of set-up. And the days would be long.

Typical Whistle Test programme schedule – studio (Live series 1984 – 85)

Timings approximate. Rehearse/Transmission on Tuesday.

09:00 – 1000 – Studio set up for pre-recorded band

1000 – 1100 – Rehearse/record pre-recorded band.

1100 – 1130 Tea break/strike down band equipment.

1130 – 1300 – ‘Blocking’ for presenter links.

1300 – 1400 – Lunch

1400 – 1600 – Continue ‘Blocking’ for presenter and interview links

1600 – 1800 – 2nd band (live act) arrive, set up, rehearse.

1800 – 1900 – Dinner

1900 – 1930 – Final rehearsals, line ups, check.

1930 – 2030 – Live transmission, usually opening and closing with the live band.

2030 – 2100 – Top Gear (wait for it, William Woollard fans!)

One of the great things about going live is there’s no editing. You come off the air. That’s it. We’ve done it. Then go to the green room and have a drink.

David G Croft

Yet, when you are responsible for the output, the day is a lot longer than that.

I would get into the office at 8 o’clock in the morning, and we wouldn’t come off the air until 8 o’clock at night. So it was yeah… it was a long day. But great.

Then we go to the green room afterwards, and I’d be sat in the corner exhausted because I’ve been running on adrenaline all day, and then I’d come home.

I’d be bouncing. I’d get home at about midnight and my wife Louise had to sit there while I gave her a blow-by-blow account the programme, because my internal system has come all the way back up again. Previously, everybody else in the green room would be chatting and having a great time, but you always know the director is the bloke sat in the corner slumped over a beer.

But that gradually wears off, and then I’d get home and want to party.

David G Croft

The Autumn edition of 1985 maintained the momentum of the previous series – on screen at least. However, viewing figures for a live early-evening show, scheduled against a soap opera juggernaut, would hang over proceedings. Possibly, as a result of this, and the competition, further change was in the air.

It did start to change a bit because I was looking at this script, and I noticed that we started to get outside broadcast injects into the show.

I’m retro thinking this now and maybe it was a case of “Hey, look at The Tube. They’ve got a live studio audience. Why don’t we have a slice of the show where we’re double emphasizing the fact that we’re live because we’re going live to a music venue.”

David G. Croft

Previously a dance hall and bingo mecca, the Town and Country Club in Kentish Town, London, started booking bands in 1985, quickly establishing itself as an important mid-size venue in London. Perhaps a desire to put itself on the map was the catalyst for a mutually beneficial arrangement with Whistle Test, resulting in a number of live performances in both Autumn 1985 and Spring 1986 series.

And that meant an increase in outside broadcasts, necessitating more directors.

In one episode of the 1985 series, Andy Kershaw noted that four live acts appearing would soon outnumber the presenters. The amount of content had dramatically increased since the Winter 1984 series. While a number of the production team would gain experience of directing, there was a need for regular studio directors.

May Miller was one of the semi-permanent assistant producers that was attached and would make films. May started doing the Outside Broadcast injects and eventually took over.

David G Croft

Yeah, May was a really good music director and became a really good producer.

When Karen (Rosie) and May did an OB together, the truck was said to visibly rock in time with the music as they moved so energetically with the rhythm.

Dominic Brigstocke

May Miller, who had recently graduated with an MA in Modern Languages at Glasgow University, was alerted to secretarial work opportunities at the BBC, and was offered a job immediately. She ended up staying in London for a decade. Pushing a desire to work in TV production, a production assistant course led, in turn, to the same competitive Trainee Assistant Producer Scheme that David G. Croft also used as a stepping stone to greater things.

During a stint in the ‘Network Features’ department, Miller ended up directing 8 Days a Week – a live music magazine programme on BBC2, of which Mike Appleton was the Executive Producer, and who accepted the request from Miller to have a go at Assistant Producing.

It was mostly making short films about artists, but eventually Mike Appleton also let me direct the studio. It was a live show when I started so he gave me a test run where he deliberately – without my knowledge – had all the cameras fail, in order to gauge my reaction. My reaction was obviously fine as I then went on to direct live studios.

May Miller.

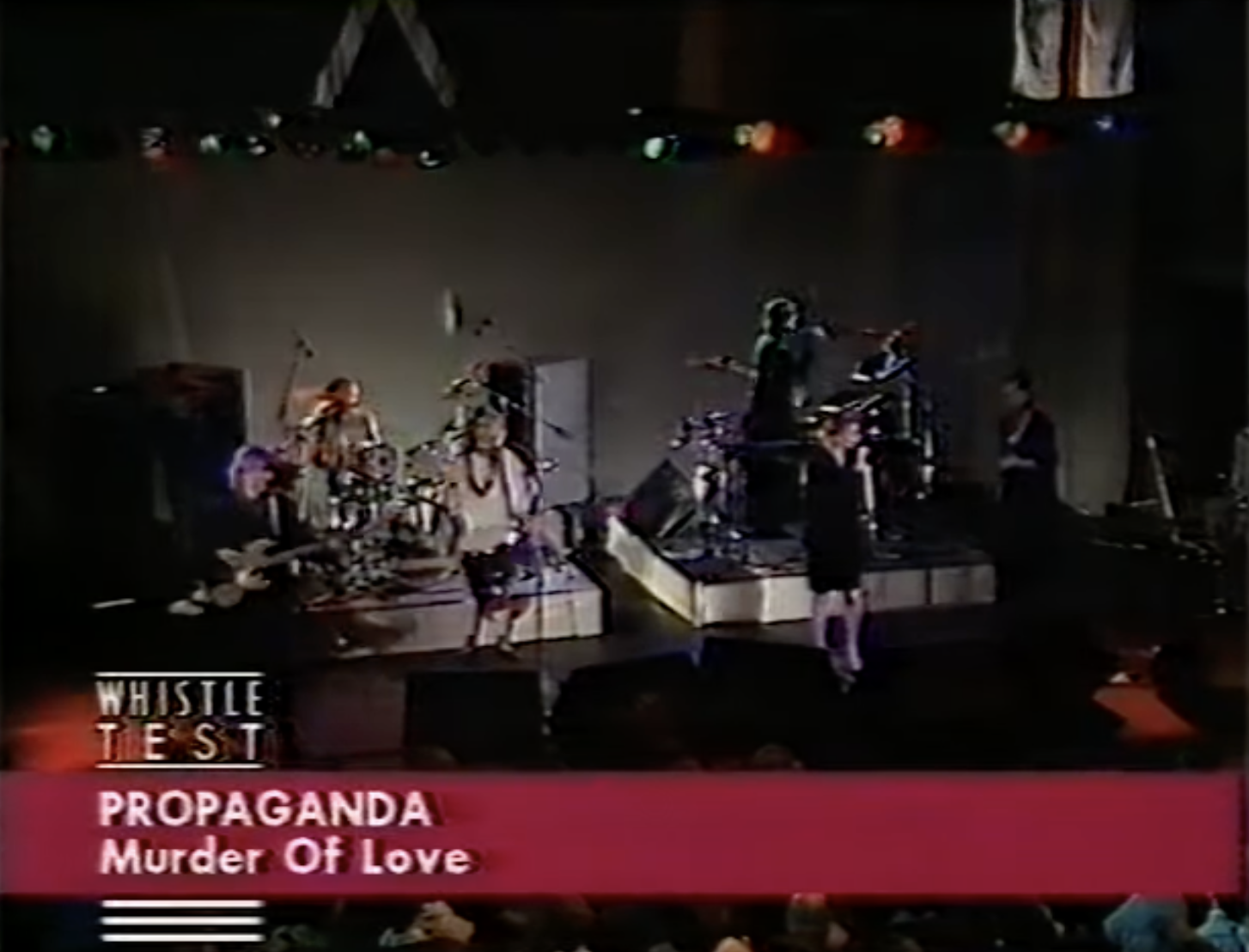

The first Whistle Test directorial job given to Miller, was during the Autumn 1985 series, capturing Propaganda live on OB at the University of East Anglia. The footage is notable for the use of a scaffolding tower – an extravagant resource for just one number. This cost £1000 (almost £4000 in today’s money), and earned Miller a “gentle scolding” from the PA.

I wasn’t a trained director so it was a bit of a baptism of fire. There often wasn’t time for proper rehearsals and you had to wing things. I learned on the job with the help and patience of others.

I had to do my own vision mixing on OB’s which if you can find The Cure at Camden Palace was not one of my high points. It was my real introduction into directing live TV, particularly music.

Often, I would turn up at the gallery and the crew would ask if I was make up, graphics, the secretary ..whatever. It was rare to have a female directing music although I never thought much about it at the time.

Tom Corcoran, the characterful director, was very helpful in trying to explain the nuts and bolts of direction with bits of string and a protractor. But it went over my head – my style of direction was a bit more random. I should have listened and then I wouldn’t have had so many dodgy shots of the crane in vision during The Cure concert.

May Miller

Whether down to inexperience or otherwise, there’s a certain verisimilitude about the footage featuring The Cure. Sure, it’s easy to spot the odd blemish, but Miller also uses an on-stage handheld camera liberally, and the long shots from the rear of the auditorium feel like we’re in the back row, getting a privileged sneak peek of what is happening. All in all, it feels like the production team is working hard to get the shots, and as a result, we’re right there in the sweat and warm beer of a packed house.

It was also a baptism of fire for Dominic Brigstocke, as he sought to use his formative experiences to open doors.

Trainees are generally given a hard time and I was no different. They’re regarded as arrogant and ignorant, so it took a while to win their trust. It was very much in at the deep end – the first time you have to direct a crew made of experienced BBC lifers is terrifying when you’re a 24 year old.

Once you’ve done it a few times, you get a bit more confident, but even today I still struggle to sleep the night before a shoot with new people.

As for multi camera studio, I thought this amazing, but got little experience as David, May and Tom did all that. I was occasionally allowed to do outside broadcasts and prerecords, but I was inexperienced and had a lot to learn. But, I have done loads of music subsequently and this was a great grounding.

Dominic Brigstocke

Based on the reflections of both Miller and Brigstocke, I’m struck by the creative hub that was the Whistle Test unit and how any creative failures or mistakes were handled by those in charge.

When I did mess up, people were very forgiving and covered up for me, which was a relief. Budget overs, shots not recorded, etc. Trevor, who was otherwise a demanding taskmaster, sorted out problems on a number of occasions. It may be that the BBC culture at the time was that if a trainee messed up, it was the producer’s fault for not supporting them, as other mistakes in other departments were also overlooked.

Dominic Brigstocke

Mark Ellen and David Hepworth were very smart and witty. I made quite a few films with them, including a rock landmarks film. Andy Kershaw brought his own inimitable style, and I remember him standing up for me when a cameraman moaned about me going hand held (again) on a shoot. The extraordinary was the every day there.

May Miller

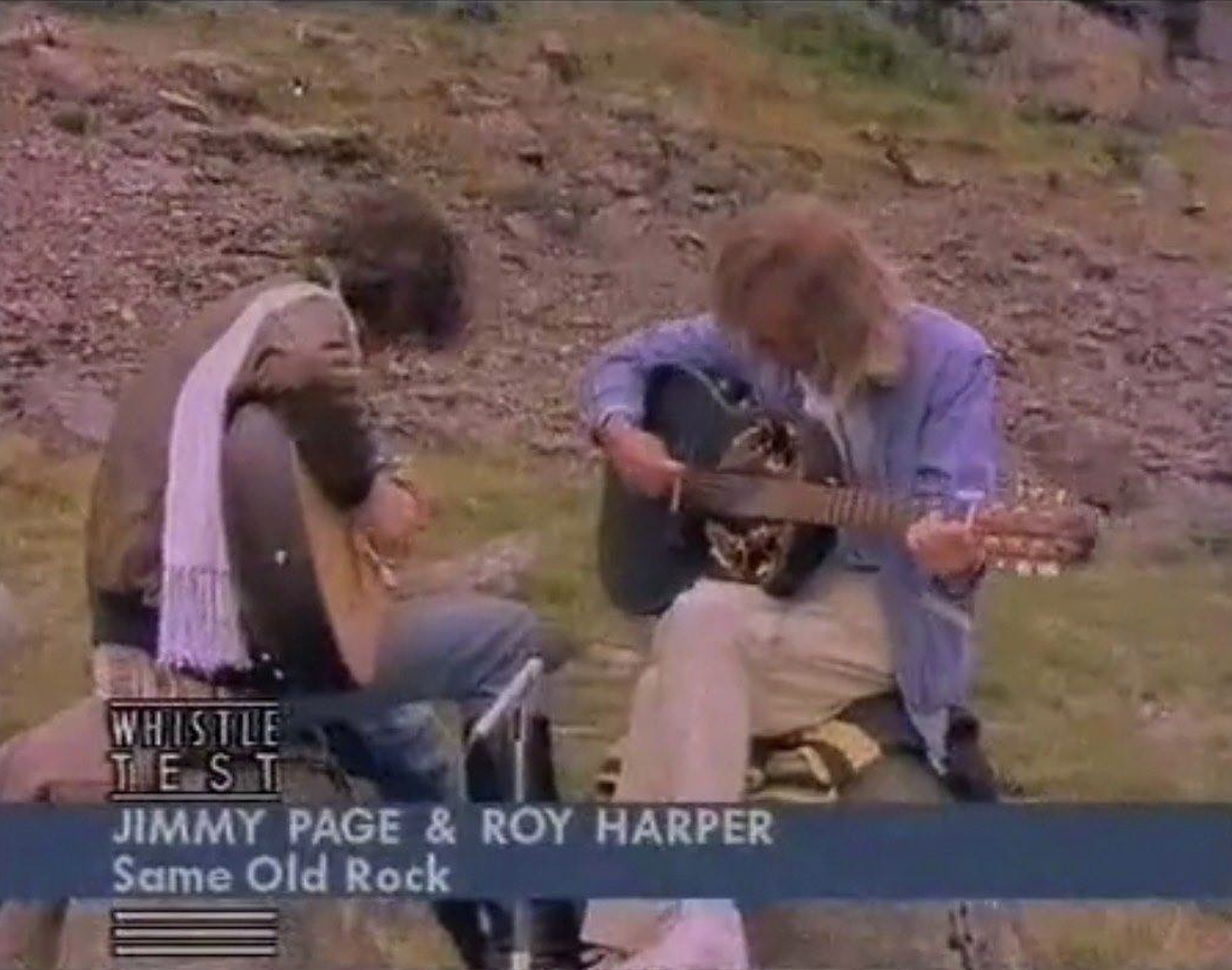

Sometimes the extraordinary could bite back. Whistle Test has a history of interesting interviews – sometimes for the wrong reasons. Bob Harris famously struggled to get much out of Van Morrison. Annie Nightingale managed to secure Jeff Beck on the agreement that a naked record plugger would play the bagpipes, and Mark Ellen battled valiantly against a tricky Roy Harper and Jimmy Page.

And now it was Andy Kershaw’s turn.

One Friday evening when I was looking forward to going home, I was deeply annoyed at being asked to go and shoot a last minute item with Bob Dylan in Crouch End. I think David G. Croft did it in the end and left me to cut it – very difficult as Bob had nothing much to say.

May Miller

This was a fact that was borne out when, during the following week, Andy Kershaw linked to the interview in question.

KERSHAW: A really funny thing happened when I was making my way home on Friday evening. I’d heard that Dave Stewart and Bob Dylan were working together, recording in a London studio.

So, I thought, “In for a penny, in for a pound, let’s go around there.” I knocked on the door and said “Can we film them?” They said “For your cheek, if you can get a film crew here within the hour then you can.” So, what you’re about to see is the first television interview that Bob Dylan has given in Britain. But a warning to Dylanologists, it’s not the Dylan interview.

The resulting interview is one of those joyous moments where rock attitude collides with television opportunity.

I phoned the Whistle Test office. We didn’t have a permanent, dedicated film crew on call 24 hours a day. And I spoke to Mike Appleton, the editor and founder of Whistle Test.

I said, “Mike I’m sitting in a recording studio with Bob Dylan in Crouch End, and he says he’ll be interviewed.” And Mike has an absolute bloody seizure. Of course he did! No one Dylan had never been interviewed for British radio or television until this point.

So, Mike had an enormous flap and somehow summoned up a BBC news crew who came up to see me. And of course by that stage I was in a state of shock, in no condition to conduct and interview at all.

…while Bob was quite friendly in these preliminaries, as soon as the film crew arrived and set up the cameras, he became taciturn and monosyllabic.

Andy Kershaw (Dylan podcast)

KERSHAW: What’s made you come to London to work with Dave Stewart

DYLAN: Well, I wanted to work with Dave.

KERSHAW: For what particular reason? What attracted you to Dave?

DYLAN: Oh he’s great.

STEWART: (amused) This sounds like a marriage guidance programme.

Indeed, Stewart could have made millions as a counsellor, as he pretty much carried the interview.

Most people, when you interview them, they want you to like them.

David Hepworth (radio interview 2017)

Bob Dylan…not bothered. Really not bothered. Absolutely not bothered at all.

The quality of capturing sound was never more important. Over its entire history – with mimed performances having been completely phased out by 1974 – Whistle Test had always prided itself on excellent quality television sound.

This emphasis on quality over quantity was another reason why one band would pre-record a studio track earlier in the day. The logistics (and money) in setting up two separate bands at the same time, during a live broadcast, was a reason for pre-recording – no doubt giving the director a chance to set up cameras and sound ready for the following item.

Bands would sometimes refuse to appear on a show if that show had a poor reputation for delivering top quality sound.

Our main competitor in this particular area of programme making was often criticised for delivering poor sound. So, the quality of the sound that we could deliver meant that we took a little longer to set things up. However, our reputation in the industry was very good.

It meant that, for the record companies and the record pluggers, they could turn around to bands and say “Look the Whistle Test sound is great. You need not have any fears going on there.”

What you sound like is what this programme is all about.

David G. Croft

Yet, once again, the music press would question this.

A glance at rock press cuttings, including the following quote from One Two Testing in Jan 1984, documenting the ‘interregnum’ Winter 1984 series, revealed the common view that The Tube was bigger and better and had more at its disposal.

…in fairness to Whistle Test and other contenders in the ever-expanding field of television rock, they are limited by the resources at their disposal, and the scale of The Tube is a measure of how seriously Channel 4 is prepared to take the business of producing a quality rock programme.

While the BBC programmes are turned round in one day in studios used for a variety of purposes, The Tube takes three whole days of preparation in its own massive, purpose-built studio before it goes on the air at 5.30 each Friday. The programme has seven cameras at its disposal, where Whistle Test has only four, and access to virtually whatever equipment is needed for the job of producing top quality sound both on and off the box.

Jon Lewin (One Two Testing, 1984)

While not necessarily untrue, it begs the question of whether the limitations of time or resources actually resulted in a lesser aural experience.

The article implied a poor studio sound, and a sense that Whistle Test couldn’t compete with The Tube‘s 96-channel mixing desk – or however big it was. This neatly sidestepped the fact that it was something that Whistle Test didn’t actually need.

The two shows were distinct from each other in their approach to sound. Although professionally recorded, presumably drawing upon the experience of prior Tyne-Tees music programmes, The Tube was about trying to capture the energy of a live stage sound, although I would argue that this was lost when listening to it via a television set. Whistle Test was the opposite – a technically proficient sound, in keeping with its faithful documentation of the studio performance.

In this regard, I would argue that the Whistle Test sound was more suited to the television medium – a quick glance at YouTube (try Robert Palmer’s The Tube performance for starters) should give you an idea.

One thing both shows faced challenges with was down to the limitations of television itself. In the case of Whistle Test, the limitations were due to the conditions of recording in a multi-camera studio.

A fable often told by Andy Kershaw is about how the BBC studio management deemed The Ramones to be playing too loud and demanded the amps be turned down from the proverbial ’11’, only for Kershaw to turn them all back up again in the moments before broadcast.

If Lou Reed, for God’s sake, is doing a sound check, and he’s too loud, a man in a white coat will come in with a little thing that looks like it’s a light meter for the Test Match and go “Too loud!”

Then you’ve got to go and persuade Lou – have you ever tried to persuade Lou Reed to do anything? The Ramones was the other example.

I think it might actually have been Tom Corcoran’s phrase, but he used to call them the ‘Programme Prevention Department’.

Trevor Dann

Every BBC studio had a microphone, hanging from the ceiling. It was called an Aims Minim. This microphone charted the sound level in the studio, and if the sound level went above – I think it was meant 80 or 90 dBs – it cut the power to the entire studio for two minutes.

When a band signed a contract to appear on Whistle Test there was a clause in it that said you will not play above 100 dBs. This was part of the contract.

Tom Corcoran was directing The Jesus and Mary Chain, and suddenly BANG! So everybody stood there looking a little confused and embarrassed for nearly two minutes, until sound was restored.

David G. Croft

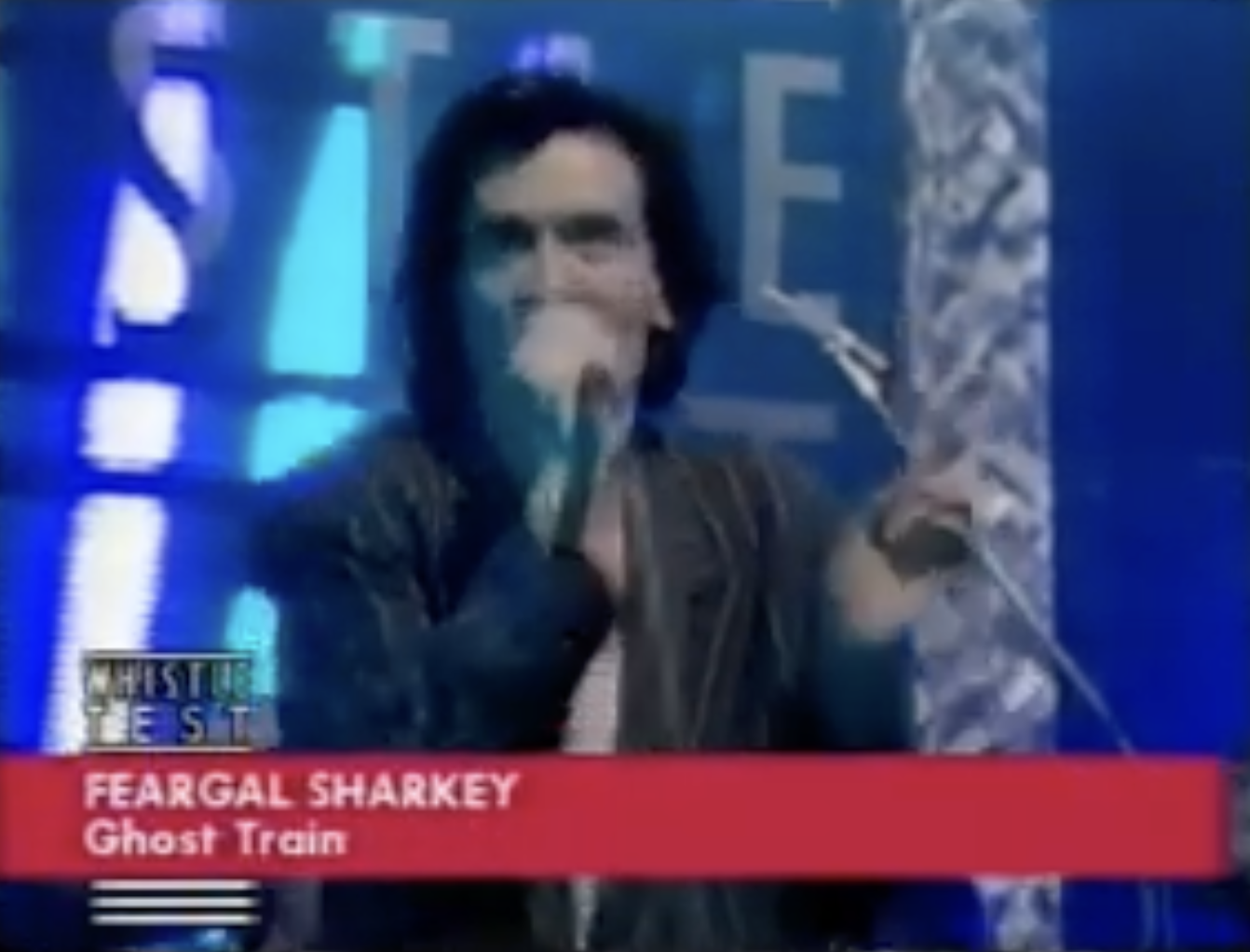

The only time it happened to me – but not live thank goodness – was Fergal Sharkey.

He had a saxophone player who blew the Aims Minim. Okay, it’s good – the beauty of rehearsals. We need to move the microphone further away. And then we were fine.

There was a reason why you couldn’t play above a certain level – health and safety. If we were doing an OB from a venue, it could be slightly louder, because they could go to 110 dBs, and if you played in the open air, you could go slightly louder again, but wobetide you.

I’ve done some outside broadcasts where afterwards the floor manager would say to me “A man from the council came holding a sound level meter while the band were playing.” So, it was taken seriously.

David G. Croft

There is an (unsubstantiated) account that the Aims Minim was the reason for the famous loss of sound at Lime Grove, when The Stone Roses performed on The Late Show.

On one occasion, the temperature in the studio was of concern. Bob Edwards was working as part of the Prefab Sprout road crew:

The OGWT was live and went out live, I remember that one. We opened the show, I had all the guitars nicely tuned, and 30 seconds before the Whistle Test title sequence they turned on the air conditioning because of the studio lights. Not sure if you know much about guitars but they dont like sudden changes in temperature, so Paddy’s guitar went out of tune and there was nothing I could do about it with a few million people looking on – for the second number they did later, it was not a problem, I had time to retune everything.

(Bob Edwards, quoted on the Prefab Sprout Gig Wiki)

The first thing to notice about the 12 episodes that made up the April – July 1986 series was the title sequence.

It’s…er…interesting.

Presumably designed by John Salisbury or Bob Richardson (credited as ‘Graphic Designers’), this sequence retains the theme music, albeit a remixed version, and the head of the chromed mannequin. However, the design is completely different.

The sequence starts with a rotating head, which is then duplicated and mirrored, and continues to rotate in different directions. The heads retain the sunglasses, and both wear headphones. The forthcoming line-up of the edition rolls across the title sequence.

Towards the end, a different set of heads appears – again mirrored. These might be the same, but appear to have bigger foreheads and appear distorted through a video effect. They do not wear sunglasses. In the background is an electronic effect, somewhat psychedelic, and distinctly videoed.

In comparison to the previous sequence, the titles are meandering. There is no narrative, the movement is aimless, and the reveal of the title caption is ineffectual. If anything, it feels like it could predate emerging dance music sensibilities, although that is perhaps being charitable.

What is curious about it is the question of why it needed to be changed at all. Was there an identity crisis behind the scenes? Salisbury, in particular, was an experienced graphic designer, so presumably this was a very low-budget approach with limitations imposed on him.

A possible lead is from a January 1986 edition of ‘Network Features’ stablemate Did You See…? In a feature about the humble title sequence, writer and broadcaster Peter York singled out what he believed to be a couple of limitations of the previous titles.

YORK: (To Camera)

Those titles have got the robot look, and neon, and laser, and electric green, and disco concrete music, and every modern motif ever. The problem is:

1) Whistle Test was always an old hippie programme, and overcompensating like this just reminds you of it.

2) This stuff dates fast, and this look is a stiffner. Robot breakdancing was summers ago, even before Whistle Test started using it. High fashion opening titles have to be right and they have to be regularly updated because a miss is as good as a mile.

While it’s a bit infra dig to knock a title sequence a year and a half after it launched, York’s comments about imagery that dates fast, and the ongoing perception of Whistle Test is of interest.

The captions throughout the programme were also overhauled, losing the banner, and the horizontal lines that served as a little visual motif, perhaps reflecting the use of Venetian blinds in the title sequence of the time. In its place was a white sans-serif font, not too dissimilar from the logo itself.

I remember they tinkered a fair bit which was possibly not good for brand recognition.

Karen Rosie

In terms of studio scenery, little had changed from the 1985 series. The postmodern stage design, and the Comfy Area were retained, although occasionally a little more moodily lit.

These might sound trivial details, but they do suggest a programme trying to find a particular style, but never really arriving at it.

However, the format remained largely unchanged, although there appeared to be a further increase in outside broadcasts fed into various points in the show. A good example is from the edition broadcast on the 13th May, which mixed studio performances from The Go-Betweens, and Latin Quarter, with a link to the Town and Country Club for an interview with Don Letts, and later on a performance from Big Audio Dynamite.

Elsewhere in the show, there were filmed interviews with Big Country, and a feature about the winner of a recent competition where the prize was to win, in effect, the services of a BBC crew to make a video with. When combined with the regular mix of promo videos, video votes, and chart rundowns, it was a busy hour of television.

In his memoir Rock Stars Stole My Life! Mark Ellen suggested an overspend during the 1986 series, although this is disputed elsewhere.

Whatever the truth, for a show as historically low-budgeted as Whistle Test was, this series might have been its zenith in terms of packing content into an edition. Further filmed forays into USA and Europe would be commonplace, and presumably not cheap. An interview and session with Susanne Vega, charting the development of her song ‘Luca’, springs to mind.

It was undoubtedly a low budget programme, but at that time there was much less pressure on costs, and record companies had very generous marketing budgets. I don’t know if it was appropriate even then but they were allowed to pay for filming trips abroad, limos, and very long lunches. Things were not as rigidly policed as they are now.

May Miller

This is a view shared by Trevor Dann, who noted that the relationship between the record companies and the BBC could be viewed as more complex.

It was like:

“Mike (Appleton), can we go and do a film with Suzanne Vega?”

“Yeah, who’s paying?”

“A&M”.

“Yeah, you can, but who’s paying for the crew?

“Well, we might have to pay for that.”

“Oh well, okay.”

It had a sense of allowing the BBC – because it was a cultural patron – to have the piss taken out of it by record companies, who would say “Would you like to make a feature about this up and coming young band?”

“Yes, we would. But we haven’t got any money.”

“Don’t worry about that, we’ll pay for it. We’ll send you wherever you want to go.”

One series of Whistle Test had in it a very bad interview with Squeeze recorded at a fun fair somewhere in the States. This was a film that Mike had shot because every summer he would go out there with Tony Berfield who’s from A&M. We were told we have to use this and it went out on television the night that Squeeze were playing the Oxford Polytechnic, which didn’t feel like it was a very good use.Bill Failer from Warner Brothers called me up and said “Would you like to make a film about A-ha? A big act. He said “Where would you like to go?” I said “Well, send me the date sheet”, so he faxed over all the gigs. I remember sitting there going “Montreal, Seattle -who cares? Oh, Dallas, Texas – now I’ve never been to Dallas, Texas”.

Trevor Dann

Meanwhile, back in the studio, May Miller was grappling with the performers and, at times, the camera supervisors.

I loved The Smiths but I got in to trouble for shooting the performance all handheld. The camera supervisor took me aside to say it would be much better if they used pedestals. He was probably right!

The Bangles were irritated that I wasn’t giving them all an equal amount of close ups.

John Lydon of PIL was an absolute pain. He had a Vicks inhaler up each nostril. It was just hard going. I had gone to meet him before hand at a gig in Barrowland in Glasgow and he was quite offhand and rude. Guess that’s his thing!

May Miller

Speaking personally, I felt the use of handheld was an ingredient that distinguished Whistle Test from its ‘Old Grey’ predecessor, making it feel contemporary. Other examples include various camera shots from behind the Venetian blinds in the background, or the out-of-focus shots that felt very apt for the studio performance from The Pogues.

Perhaps May Miller’s recollection is a good reminder of the balance between the production team’s new sensibilities and the BBC technicians’ traditions of the era, rooted in the need to make quality television within the ‘studio-factory’ context.

Alma Player was the researcher on OGWT when I arrived. She had been with Mike and the team for a long time and I learned a lot from her.

Karen Rosie

Alma was like everybody’s mother. She was the show’s researcher. And she’d been there from the beginning and she was just lovely. Smoked like a chimney and had a wonderfully deep voice.

David G. Croft

Photo – Mark Ellen https://rockstarsstolemylife-blog.tumblr.com/image/83703824055

As one of the new young members of the team, I was very keen to know what was the filing system for Whistle Test. How could I find performances by X, Y and Z? There was this card index in a plastic box.

Alma categorised every band prefaced with ’The’ under the letter T. So, The Beatles, The Who, The Stones, The Kinks. But she had her own way of finding stuff.

She was lovely. If you wanted to find clips of stuff, she could be like a bloodhound. She was, in those latter years, a bit like a mascot. She was great.

David G. Croft

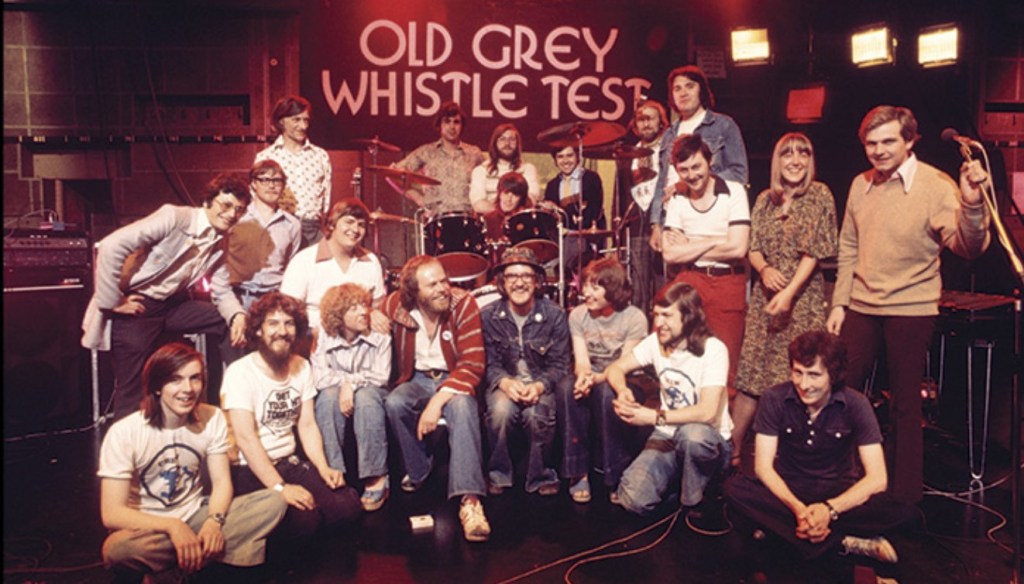

(Top right, with blue denim jacket) Mike Appleton – 1977

And as for Mike Appleton.

I’m not sure what he actually did from day to day (I think general management), but he was very nice and we didn’t see much of him – he certainly didn’t interfere with the producers.

Nowadays, he’d be called Executive Producer and have several layers of management above him. We were very much left to get on with it. I think he spent much of his time trying to persuade record companies to let us have their best bands rather than putting them on The Tube, and I think the record companies played games with the obvious rivalry between the two shows, but there would also have been general BBC management issues (budgets, schedule, ratings) which he was dealing with.

Dominic Brigstocke

No doubt, it was the scheduling that would have been preoccupying Appleton the most. For this series, Whistle Test was shifted even earlier in the evening. This was presumably due to the EastEnders sized dent in the viewing figures. The money would have been on a shift to later in the evening. However, Whistle Test now went up against the national news on BBC1, and regional news programmes on ITV.

Over the next few years, a 6pm timeslot would be the natural home of many ‘youth’ or specialist programmes – the Def II strand from 1988 onwards would start at this time, and famously The Simpsons into the 1990s. Maybe there is an argument that this was a carefully considered rescheduling, positioning Whistle Test in the same domain as other programmes designed for a younger market.

The trouble is that Whistle Test, even in its revamped form, wasn’t solely a programme for a young audience. Trevor Dann recollects an idea that didn’t work out.

Around this time, we also had a repeat. So, I came up with this idea – deeply unpopular – which was “Why don’t we try and keep in touch with some of our older fans by having a slightly different slant on the show during the late night repeat?”

The example of this that always gets quoted, is when we got an interview with Ry Cooder. I said there’s no point in putting Ry Cooder out at 7:30pm, in a show I think the star turn might have been the Pet Shop Boys or something.

There was no point in doing that because people who were attracted to this new younger format would not have a clue who he was. Equally it would be wrong to just put him on for three minutes and cut it all short, whereas on the repeat you could make it a bit longer.

So I tried to persuade David (Hepworth) this was a good idea, and he absolutely hit the roof and said it was unkind and unfair and he shouldn’t just be put on a repeat show – he should be on the main show.

So, that that one didn’t work but by then you know the whole kind of atmosphere had deteriorated. That idea ran for a couple of weeks, but it never did get off the ground.

Trevor Dann

Another consideration was that Whistle Test was very much ‘live’ – a magazine format crammed with live OB feeds, studio performances, and more expenditure than it had ever experienced. The series suddenly became very costly for that particular timeslot, even with the benefit of a late-night repeat later in the week (which usually featured an extra or elongated track from a studio band.)

I think one of the assumptions that a television audience has, is that when you make a programme you decide when it’s going out. Of course, it’s a big shock when you realise that you don’t!

There are these chaps, up on the sixth floor. Quite often, they make decisions that run absolutely to the benefit and health of your programme and particularly if the programme is new. I learned this at the BBC – you had to fight your corner with the schedulers, because that’s where the big hitting juggernauts got pride of place.

So, it’s a tricky business. It’s massively frustrating because it leaves you defeated, and feeling that they don’t care. Of course it’s just that their priorities are different – sometimes you become the victim of scheduling to the detriment of the programme.

David G. Croft

It was definitely expensive compared to what it had been like. So, in some ways we’d won some of the arguments – we had said “give us a bit of money, give us some better studios, and we’ll make you a live show, and it’ll be better.”

Well, problem one – you can’t make it like The Tube because you can’t have a live audience, because we can’t give you a studio that’s got a live audience. So, there was nothing we could do about that. It was going to be live music in an empty studio however you played it, and you know that’s not a great winner.

Trevor Dann

The 12-part series ended in July 1986, but the production team continued the tradition of special editions, focusing on a single act, usually under the banner Whistle Test Extra. Bryan Ferry, Joni Mitchell and Stevie Wonder were highlighted.

Quite early on, I was sent out to film an interview with Mark Ellen and Stevie Wonder. This was off-the-scale amazing for a young trainee, and I was allowed to cut it into a half hour special which was a huge break for me. He was completely lovely and modest and charming. A truly talented saint.

Dominic Brigstocke

There might have been a sense that the long-term future of Whistle Test was on the line, but even in 1986, the production unit was very active.

A final all-nighter Rock Around the Clock would be aired over 12-and-a-bit hours in September – save for interruptions from News View (the subtitled news review of the week), and a spot of Championship Darts.

Featuring Stan Ridgeway, Echo and the Bunnymen, and a hip-hop duel involving Faze One, (who I recall getting a lot of airplay on Janice Long’s Radio 1 show), the marathon ended with a tribute to Whistle Test, which celebrated its 15th birthday on that very day.

Getting a prime time slot was perhaps Dominic Brigstocke’s most notable contribution – London 0 Hull 4 – a documentary about The Housemartins, which felt like an authentic snapshot of northern England during Thatcher’s Britain.

I remember doing a half hour special with The Housemartins in Hull which was (Dominic Brigstocke’s) idea and he directed. Was a miserable day weather wise – we were on a boat for some of it but the tunes were good and look at what they did next!

Karen Rosie

Another familiar Whistle Test special of the era was the spotlight on ‘The Rolling Stones’ – Work Five Years and 20 Years Hanging Around. David Hepworth was assigned the presenting duties. The show plays out like a Nick Broomfield documentary. At the film’s end, Hepworth loiters backstage and captures a forlorn-looking Charlie Watts, who perhaps delivers his ultimate bon mot.

WATTS: (Resigned) It’s quite hard work… some of it… as you notice today. I mean what have we done? Nothing, but sit around.

HEPWORTH: you must have done a great deal of hanging about in 25 years with The Rolling Stones.

WATTS: Work five years and 20 years hanging around.

The 1986 series, alongside the specials that existed around it, represents Whistle Test at its most ambitious. Indeed, a number of the production team make reference to a budgetary increase for the live shows, and in the same breath mention the words “by Whistle Test standards“.

I would guess that channel controllers wouldn’t be thinking about comparisons with OGWT, they would be considering the performance of the series and where it fits within the channel.

Yet, listening to the contributions to this article, it’s hard to ignore the possibility that Whistle Test was – symbolically at least – a victim of its own frugal budgeting when it was ‘Old’ and ‘Grey’, and part of a BBC department that was synonymous with producing shows cheaply.

Network Features had been born out of Presentation Programmes, where the presentation department had started using its tiny studios to meak every cheap programmes for BBC2, usually late night, So OGWT, Film ‘86, Did you See..?, Late Night Line Up, all got made in this tiny ‘Pres B’ studio – hence OGWT having no set – there wasn’t room, or money!

On one occasion, I was told, when a band was big, they had to shoot through the door from the corridor as they were exceeding the weight load on the studio floor. As long as these shows stayed cheap, they were very popular with the controllers: Barry Norman and a chair and free film clips was a very cheap programme.

Once Whistle Test was taking up a proper large studio with a set and films and four or five presenters, and an hour long, it started to look less good value. I suspect people expected it to get bigger viewing figures, but in those days 1.5 million wasn’t good enough that early in the evening.

Dominic Brigstocke

Presumably, this was a fact not lost on the production team, who must have felt like they were fighting a losing battle with unforgiving scheduling, a looming departmental restructure, and a changing attitude to music television within the BBC.

Despite our best efforts to attract younger viewers we were beating our heads against a brick wall, because Alan Yentob was already wooing Janet Street Porter with a brief to revolutionise BBC youth television.

John Burrowes

All of this must have amplified the existing competition between the two production teams. In an energetic, creative hub, the line between healthy and unhealthy competition can often be a delicate one.

I got the impression there were two ‘producer’ camps with Trevor and John Burrowes and there was a bit of friction or competition between them! As a young person (I was just 21) it was a lot to navigate but I was just grateful for the opportunity.

Ro Newton

There was intense competition between the teams which became unhealthy at times, especially when the show was clearly in danger of being cancelled. Tom was delightful, lovely to everyone and generally loved by everyone, loved a practical joke. John and Mike were similarly laid back, in a very Auntie/traditional BBC style, which contrasted with Trevor’s relative youth and ambition, and greater knowledge of music, so there were unspoken tensions all the time.

A lot of it was unspoken and fairly light hearted. I was the trainee and caught in the middle as I worked for both teams, so maybe I was more aware of it.

As I understood it, Trevor had brought Andy Kershaw into the team as someone who was passionate about music and different to the run-of-the mill southern TV voices, and they tended to work together more, although Andy was ALWAYS committed and professional in everything he did.

From my perspective, things between the teams became worse as the chance of the show being cancelled became more likely – meetings were increasingly tense and things were said (I remember my films being harshly criticised by one team only for the other to defend them!), but I don’t think it made any difference to the output. People still booked the best bands they could get and made the best films they could. There was nothing anyone could do to get the viewing figures up.

Ironically, new comedies like The Office and I’m Alan Partridge didn’t get better figures on first transmission (about 1.5 million) which just shows that it’s all about expectation rather than the actual number.

Dominic Brigstocke

While Whistle Test maintained a visible profile on BBC2, 1986 was the first year which a greater number of the 52 weeks didn’t include a weekly edition or special. Following the heady heights between the live re-launch in October 1984, and Live Aid in the summer of 1985, Whistle Test had been truncated. Both the Autumn 1985, and Spring 1986 series returned to a 12-show run, a familiar quarter-year length to most of the series since 1982. Presumably, money was the reason – it usually is.

It was clear that even before the final axe fell, Whistle Test would need to cut costs.

Next Time – The final series, and all change at the BBC. No Longer Old, No Longer Grey – Part Five.

References and acknowledgements at the end of the final chapter.

Leave a comment