Tim Dickinson

MA by Research – Arts University Plymouth.

Submitted July 2025.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Jason Hirons and Eddie Falvey for challenge, assurance, and encouragement. Thanks to Tif Dickinson for space and understanding, and knowing that proof-reading might put a strain on the marriage! Thanks to numerous people who are invested in Doctor Who, from friends in the Blusky community, some of whom are referenced in this thesis. Also, thanks to Donna Gundry, David Brunt, Nicholas Pegg and Paul Scoones for taking time to answer a specific question, or dig out old paperwork – this helped move the writing forward.

Abstract

One reason for the longevity of the BBC series, Doctor Who, is that it can be divided into a series of ‘eras’, often characterised by particular tonal and stylistic sensibilities that reflect the authorship of the BBC producer in charge. These eras have been reviewed and assessed by fans, critics, and scholars over the decades, often resulting in a number of critical orthodoxies that shape the established history of the series.

This thesis will argue that these orthodoxies are, by-and-large, determined by the pleasure of the critic, a dominant mode of screen critique that is rooted in the traditions of English literary criticism. This reduces the study of value – defined here as how the series perpetuated itself, and creatively reflected (or reflected by) social, cultural, and industrial contexts.

Two producers helmed Doctor Who between the mid-to-late 1970s – Philip Hinchcliffe and Graham Williams. Both produced the series under very different conditions, and therefore have contrasting reputations. By studying the production of Doctor Who through the lens of innovation theory, it is possible to reassess the traditional ‘lore’ that surrounds the reputation of these two producers, their contributions to Doctor Who, and the television industry more widely. I will argue that, where traditionally the output of one producer is favoured over another, in fact, both producers equally innovated both proactively and reactively, while retaining their own authored vision for the series.

Research is gathered through secondary methods including: documentary evidence, personal testimony, written reviews, and textual analysis. The thesis is written for those invested in the show – audiences, fans, and scholars. It is also beneficial to those working within the creative industries who are responsible for managing change in established brands, while navigating different contexts and climates.

Contents

| Page | |

| Title | 1 |

| Acknowledgments | 2 |

| Abstract | 3 |

| Contents | 4 |

| Introduction | 5 |

| Chapter 1 – What Makes Good Television? | 10 |

| Chapter 2 – Innovation ‘out of the box’ | 20 |

| Chapter 3 – Producer Innovations | 26 |

| Conclusions | 48 |

| List of illustrations | 52 |

| References | 57 |

Introduction

In 1976, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) transmitted an episode of its long-running science-fiction/fantasy series Doctor Who. Since 1963, the series had been a regular ingredient in the BBC’s celebrated Saturday evening lineup, enjoyed by adults and children alike, with high viewing figures and often outperforming its competition on commercial television (Chapman, 2006, p99).

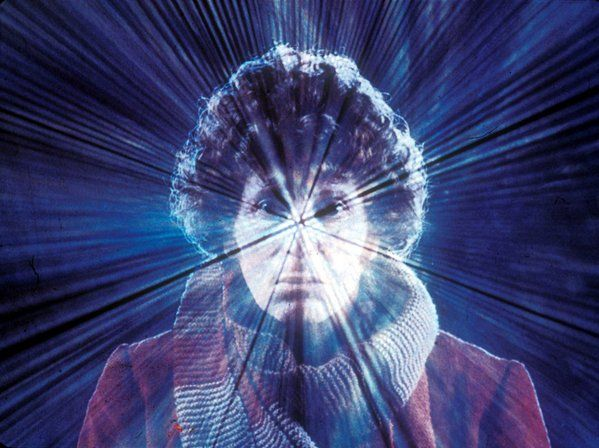

Fig 1. Bernard Lodge. (1974) Title Sequence for Doctor Who.

Part three of the four-part serial—‘The Deadly Assassin’—transmitted in November 1976—was a remarkable innovation and a departure from the familiar characteristics of Doctor Who. The eponymous Doctor fights for his life without an established secondary character at his side, and within an illusory environment containing an array of arresting images and sequences shot on location using film, rather than in the studio on videotape.

While a departure from the norm, it can be argued that the innovative nature of this episode was less extraordinary because it was scaffolded upon smaller, incremental innovations that had been introduced by Doctor Who’s producer of the previous two years, Philip Hinchcliffe.

Within the television industry, the BBC producer held the same status as a film director, being ultimately responsible for a series of programmes, artistically, editorially, and financially (Nathan-Turner, 1988). This is significant within a long-running series, such as Doctor Who, which is often categorised as a series of eras, based on the values and sensibilities of the producer in charge (Rolinson, 2007, p176).

Hinchcliffe is a celebrated figure within Doctor Who. For many, the assessment is of a ‘golden era’ (Brown, 2015) – a producer who increased Doctor Who’s viewing figures, gave fresh impetus, and pushed boundaries in terms of tone, use of genre, characterisation, depiction of violence, and production values (Chapman, 2006, p98).

Part three of ‘The Deadly Assassin’ was a pivotal moment within Doctor Who, climaxing with a violent battle in water, and an attempted drowning of the Doctor.

As part of the National Viewers and Listeners Association (NVLA), right-wing Christian TV campaigner Mary Whitehouse had lobbied the BBC about taste and decency since the 1960s. This particular depiction of violence offered the opportunity to throw the BBC’s own editorial guidelines at the corporation. This earned an ‘apology’ from the higher echelons of the BBC management, the permanent re-editing of the master tape, and a shift in how Doctor Who was produced, depicted, and scrutinised (Wood, 2023, p311).

Fig 2. David Maloney (1976) Doctor Who – The Deadly Assassin

Hinchcliffe departed, and Graham Williams was installed as producer. Where Hinchcliffe enjoyed comparative creative freedom, Williams faced several directives and impositions. Some were institutional – a result of ‘The Deadly Assassin’ – and others were beyond his control.

While the BBC’s acknowledgment of Whitehouse’s argument was a tipping point, the tenure of both producers was marked by a significant change of circumstances and fortune, subsequently resulting in significantly differing reputations. This poses interesting questions regarding the drivers of authorship, innovation, boundary-pushing, and the nature of orthodoxy.

Fig 3. Tony Cash. (1977) Doctor Who producers. Phllip Hinchcliffe (1974–77) and Graham Williams (1977 – 80)

This thesis will consider boundary-pushing, largely – but not solely – in connection with production technique. It will enquire whether studying Doctor Who through the lens of innovation theory can expand how the show is ‘read’: the expectations of the viewer, the nature of screen-based criticism, and whether this provides an opportunity to reassess producer reputation.

Although the subject sits within the realm of the television scholar, there are the contexts of sustaining a long-running cultural phenomenon, the limitations and opportunities of innovation and boundary-pushing, and the social and cultural considerations inherent within. This offers interest to anyone involved in producing, organising, and realising any creative endeavour within the visual arts.

The first chapter explores modes of screen-based criticism. By considering how television is historically ‘read’, and notions of ‘quality’ or ‘good’ television, this thesis will pose that the history of Doctor Who is primarily written from a position of ‘pleasure’ rather than of ‘value’. From this, the established critical orthodoxies of Doctor Who during the eras of both Hinchcliffe and Williams can be traced. By drawing upon a range of historical and contemporary viewpoints from fandom, audiences, critics, and those working in television, the reputation and legacy of both producers will be established.

The second chapter will identify production methods of television drama of the 1970s, alongside different modes of innovation theory. The third chapter applies these to the production of Doctor Who by examining case studies from both producers; having identified different industrial, political, social, and economic factors inherent during both producers’ tenure, the chapter will seek to find similarities and parallels, allowing conclusions to be drawn.

The conclusion will draw this evidence together and consider producer vision, the impact of the innovations, and how this contributes to producer reputation and critical orthodoxy.

Although this study does not seek to change or influence established reputations, it is hoped that it can contribute to an expanded reading of Doctor Who from this era, and television more broadly, through distinguishing the difference between ‘criticism of television’ which Corner (2006) notes is widely disputed, but often veers towards the social impact inherent in this form of mass-communication, and ‘television criticism’, or ‘stance’ described as something which has a tradition of literary criticism, and is centered on appreciation of the textual form as aesthetic object that possesses ‘a certain level of autonomy from the conditions in which it is produced and consumed’ (Corner, 2006).

Indeed, Corner makes the case that thinking beyond the textual, and making stronger connections with different modes of thinking and enquiry, can support television studies in developing ‘better as a discourse of knowledge as well as a discourse of cultural dispute’. And while ‘value’ and ‘worth’ is often associated with political, social and cultural contexts, removed from the textual, it can open up new modes of enquiry and critical debate by paying attention to human endeavour within the form of television, rather than simply its output, and providing a bridge between our understanding of how pleasure informs a critical assessment (our reaction), to the conditions and thinking behind how it was made.

Chapter 1- What makes good television?

The notion of ‘good’ television opens up a broad range of arguments that encompass form, prestige, value, quality, and pleasure.

Charlotte Brunsdon (1990, p59) argues that a tradition of ‘good’ television is derived from high or middlebrow culture, such as the arts, theatre, or literature. By bringing these forms to the screen, these legitimate artistic sources can be accessed by a wide audience. This partially explains the prestige of the ‘single play’, as exemplified by the BBC’s Play for Today strand that ran in different forms from the 1960s to the 1980s. This was seen as culturally important and critically acclaimed for its boldness and emphasis on authorship (Rolinson, 2013). Emerging and established writers, producers, and directors had the opportunity to explore alternative modes of expression, where established grammar could be subverted. The ‘single play’ was seen as a sometimes expensive form of public service broadcasting (PSB), promoting the idea that television could be ‘prestigious’ and ‘improve’ popular taste and national culture (Caughie, 2012, p128).

Brunsdon (1990, p60) also argues that the opposite of ‘good’ television is not ‘bad’ television, but something more populist in nature. The emergence of the ongoing series or serial was treated with suspicion or disdain from some quarters, who considered ‘good’ television as broadcasting steeped in colonial or British traditions, rather than from America.

Brunsdon cautiously notes the difference between ‘good’ and ‘popular’ television risks much formulaic, or ongoing television, being devalued or disregarded in critical discourse.

To put this another way, only when somebody you wouldn’t expect (for example, Paul Theroux) watches a genre programme, Coronation Street, is the programme interesting. And what is seen as interesting is precisely how the author gets on with the not-good programme

(Brunsdon, 1990, p61.)

If the synergy between ‘good’ television and authorship reduced the value of collaboratively-produced genre series, often including recurring and repetitive situations and characters (Bignell, 2005, p76), the 1970s acted as a watershed period, where the business of television production gained importance, and the ‘value’ of the single play (expensive and harder to market) gave way to the more economical series/serial (a form that commanded ongoing loyalty within its audience) (Caughie, 2000, p204). This accelerated during the inflation-hit 1970s, where budgetary scrutiny became more acute (Cooper, 2024, p54), but also coincided with an increased perception of value and quality of the series/serial within international television markets in the mid-to-late 1970s (Caughie, 2012, p52). The syndication of Doctor Who to America is a case in point.

What does this say about how television was read and critiqued? Caughie echoes Brunsdon’s observations about ‘good’ television belonging to legitimate artistic forms, by arguing that screen-based criticism was historically based on the traditions of English literary criticism, being more concerned with how meaning was produced than with the ranking of works on a scale of value. Again, an ongoing series such as Coronation Street is used as an example. If one identifies a single value and compares King Lear to the soap opera, Coronation Street would rank second, due to ‘value’ being largely ideological in nature. Caughie (2000, p21).

To establish how ‘pleasure’ is paramount in how a continuing series such as Doctor Who is read, it is worth tracing a line through the established critical orthodoxies the show during the eras of both Philip Hinchcliffe and Graham Williams, and how these established perspectives are derived.

In 2024, a new retrospective of Hinchcliffe’s work was published. The DNA of Doctor Who: The Philip Hinchcliffe Years, offers a series of short essays written by established and emerging names within Doctor Who fandom. This accompanies commentary by Hinchcliffe himself, and maintains a firmly rooted celebration of what has been established as a ‘Golden Era’ of Doctor Who.

It was not the first time his era was singled out for tribute. In 1996, Classic Who: The Hinchcliffe Years was published, promising ‘the most in-depth investigation yet written of this period that many see as one of the creative high-points of Doctor Who.’ (Rigelsford, 1996).

Both publications demonstrate a synergy between fan opinion and Hinchcliffe’s own authored account, offering opportunities to ratify his reputation within fandom. The 2024 publication cleverly uses personal, bite-sized accounts from Hinchcliffe that often frame each individual fan-authored essay. Themes such as ‘exorcising the past’ or the production contexts of multi-camera drama can be surfaced throughout the book, and further cement already established opinions, and enhance the sense of appreciation.

While Hinchliffe’s reputation has remained largely unchanged over the past 40 years, the assessment of Graham Williams is more complex and uncertain.

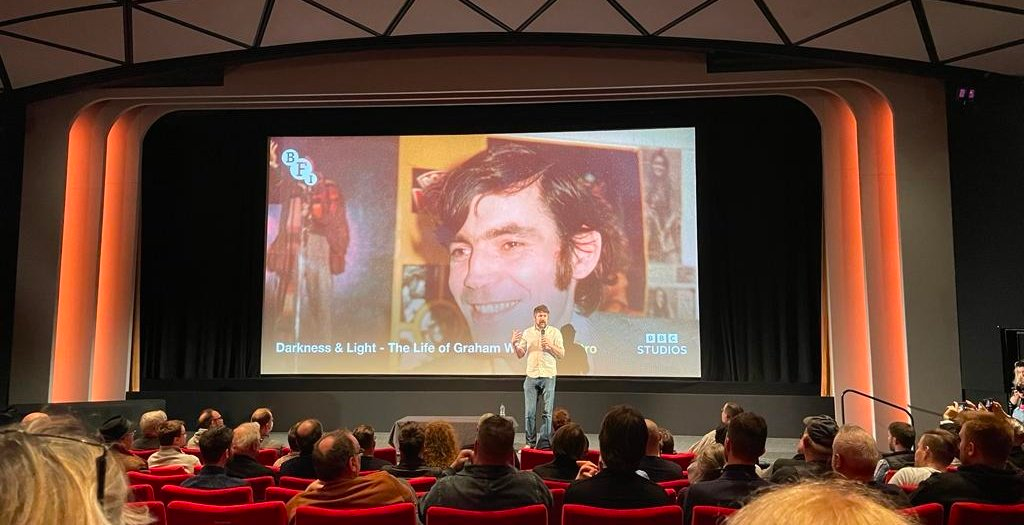

In early 2024, the British Film Institute (BFI), and BBC Worldwide celebrated the forthcoming Blu-ray collection of the 15th season of Doctor Who with a series of screenings and interview panels at the BFI Southbank cinema. During the event, filmmaker Chris Chapman (2024) premiered a retrospective documentary feature on Graham Williams – Doctor Who: Darkness and Light – The Life of Graham Williams.

I hope it’s a chance for Graham to get a moment in the limelight that maybe he has never really been afforded. I think that I admire and enjoy Graham’s imagination. We always talk about Doctor Who as the ultimate format, and it is so boundless and it can do anything. And Graham was boundless in this way, regardless of BBC budgets and industrial action, and a star who might not be in the best mood that morning. And I really admire that about him, that he persevered

(Chapman, 2024).

What is interesting about the framing of Chapman’s comment is that it speaks of not only pleasure and aesthetics, but also a position of ‘value’, by recognising that Williams was responsible for a series that transcended the limitations that he faced, to produce a show for a broader audience and with a wider scope.

Fig 4. Chris Chapman (2024) introducing ‘Doctor Who: Darkness and Light – The Life of Graham Williams’ at the BFI.

Chapman’s documentary is important in that it positions Doctor Who within the context of Williams’ approach to writing, editing, and producing television. The development and value of the idea is a central theme, and the film portrays this as a key strength of Williams (Sherman, in Chapman, 2024). Yet, there is an occasional suggestion among his peers, and present-day fans of the show now working within the television industry, that his drive for ambition got the better of him, resulting in unachievable ideas (Mapson, in Chapman, 2024) or that his personality impacted his producership (Jameson, in Chapman, 2024).

Nonetheless, the film goes a long way to reassessing Graham Williams’ era, with a new angle focusing on his personal and professional life, character, and approach. Although the film reveals the tragic circumstances leading to his untimely death, it doesn’t significantly alter the already established orthodoxy – this his era isn’t as highly regarded as Hinchliffe’s.

Chapman’s ‘moment in the limelight’ comment suggests that Williams’ contribution to Doctor Who is assessed or appreciated to a lesser degree than Hinchcliffe’s. The self-defence for Williams’ work on Doctor Who is largely attributable to a handful of archival interviews given through print, video, and audio. Therefore, the narrative of Williams is increasingly determined by the perception of his work by fandom, with the resulting emphasis on ‘pleasure’ (or otherwise) diminishing the personal and industrial factors that shaped his on-screen output and resulting discursive reputation. Furthermore, there is an imbalance in some prominent publications that provide ample coverage of Hinchcliffe and the perception of a ‘footnote’ for Williams (Sandifer, 2014, p12).

In contrast, fan commentary of Hinchcliffe often mirrors the producer’s own testimony. A good example of this can be found in reflections made by Toby Hadoke (a popular and prominent figure in modern-day Doctor Who fandom) within the 2024 Hinchcliffe retrospective.

This is because Hinchcliffe and Holmes don’t underestimate their audience – the stories are awash with subtext and they trust us to pick it up.

…Hinchcliffe knows that in order to work, Doctor Who needs to be popular, dramatic, dynamic television – to thrill the kids, but keep the adults on board too.

…for the sake of balance, one must be honest about Hinchcliffe era imperfections elsewhere (despite, ultimately, forgiving them)

(Hadoke, 2024, p14-19).

An imbalance is created between Williams’ early passing, and Hinchcliffe’s continued engagement with fandom over 50 years since he produced Doctor Who. Hadoke’s valid assessment echoes Hinchcliffe’s perspectives on producing television and the freedom he had to do so. Yet, it can be argued that popular, dramatic, and dynamic characteristics are also traits of the less-regarded Williams era, whose stories were also awash with subtext, and trusted the audience to pick these up. There is also nothing to suggest that Williams ever underestimated the audience.

Given that much fan opinion is based on a notion of pleasure, it can be questioned whether the circumstances that affected Williams’ era are diminished in the assessment; thus we rarely forgive his work, as Hadoke suggests we might forgive Hinchcliffe. I would argue, therefore, that Hinchcliffe is more commonly defended, and Williams is more commonly prosecuted.

Interestingly, a rare example of prosecution scrutiny can be evidenced in an interview with Hinchcliffe, conducted by Matthew Sweet in 2021, where Sweet gently probes the circumstances behind the removal of Hinchcliffe as Doctor Who producer, in the wake of ‘The Deadly Assassin’ furore, both acknowledging and subtly challenging existing wisdom that he was transferred from the series. The suggestion that he was removed or ‘sacked’ from the series is less commonly articulated. It’s one of the few times that there is an uncertainty between Hinchcliffe and the commonly perceived fan view, with the producer appearing slightly irate and defensive (Vanezis, 2020).

Tracing backwards the line of long-standing critical orthodoxies, fan commentary often speaks of personal satisfaction, namely a ‘heavenly’ mix of horror and television (Farley, 2015), or lamenting the switch from Hinchcliffe to Williams.

And lo, the great Hinchcliffe had his power cruelly ripped away […] [under Williams] Anarchy was loose: robotic dogs, gigantic prawns, dancing bulls, glowing green phallus-monsters, yay, even unto Catherine Schell’, until Nathan-Turner ‘dragged things back from the brink of disaster’

(Wigmore, 1996, p22-25).

A modest comparative study of how both producers are assessed, based on the same common themes, reveals the impact of pleasure over value. The narratives initially start with a similarity – that both producers wanted Doctor Who to evolve. An assessment of Hinchcliffe will often acknowledge his inheritance of a stable and popular series, allowing him to use a pool of established writers, directors, and other production staff (Sweet, 2024). It is interesting to note that Hinchcliffe speaks of colleagues as a crucial element in developing innovations. Bonds with script editor Robert Holmes, new lead actor Tom Baker, and a substantial handover with previous producer Barry Letts, enabled Hinchcliffe to start from a position of proactivity (Hadoke, 2024 p14), approaching the show as one that was successful, but also had to aim upwards, in order to maximise its audience (Hinchcliffe, 1983, cited in James Walker, 2006, p153). This is amplified by his joining the BBC from ITV, unaware of institutional process and ‘red tape’. He felt a part of the zeitgeist of innovation and was interested in pushing the envelope (Hinchcliffe, 2024, p153) – an ideal foundation for any new producer.

The narrative moves towards a lauded, winning formula that matured during his three seasons on the show. There is much evidence to suggest how his approach nudged the formula or prevented stagnation or complacency (Hinchcliffe, cited in Vanezis, 2020).

…just as we all know that the Hinchcliffe era was a previous occasion where, generally, it all fell into place and everyone was at the top of their game. We know this to be true, just as we know that it was because Hinchcliffe was partnered with a script editor who was of a like mind to terrify the kiddies into becoming a nation of bedwetters.

(Sangster, 2010, p259).

This assessment reflects the commonly held perception in television criticism that ‘quality’ is connected to a reaction to what is seen on the screen – dramatic emphasis, high production values, and ‘good’ acting (Weissmann, 2015).

Williams’ assessment also begins by establishing the series he inherited from his predecessor. However, in contrast to Hinchcliffe, his handover from Hinchcliffe was abrupt and lacked a support structure to help him into the role. Indeed, his first day in the studio left Williams feeling trepidatious, like he had come out of the ‘Stone Age’ (Williams, cited in Chapman, 2024).

However, an emphasis on the critics’ pleasure means Williams’ approach is often not lauded, and as a consequence there are many suggestions that his approach was a sign of inconsistency, passivity or ineffectiveness as a producer, as noted by Cornell, et al (1993, p308), or that the show was perceived by fans as ‘shoddy and lazy’ (MacDonald, 2004, p7).

Following this, a different and inconsistent mode of assessment emerges. Instead of Williams’s output and approach being assessed on its own terms (as applied to Hinchcliffe), the narrative often moves to how Williams’ era compares to his predecessor. Critical opinion of two serials, ‘Horror of Fang Rock’ and ‘Image of the Fendahl’, is often celebrated as ‘last gasps’ or ‘worthy’ of the Hinchcliffe era, (McGown, 2023, p49) rather than as an expression of Williams’ own approach.

This imbalance expresses a wider perception of both producers as broadly proactively successful or reactively unsuccessful in their endeavours. In a biography of Robert Holmes (a script editor who worked with both producers), the difference between the producers are articulated in contrasting terms.

But in terms of producing styles, Williams was more of a ‘dove’ (tending to follow the trends and expectations of his management), whereas Hinchcliffe had been more of a ‘hawk’ (tending to produce work that was against the grain and groundbreaking), and Bob must have felt increasingly like a fish out of water in the Doctor Who production office

(Molesworth, 2013, p318).

The 2024 Hinchcliffe publication and Williams documentary highlight two very different reputational legacies – a joy and a curiosity; the joy of celebrating a much-loved era, and a curiosity in unpicking the work of a producer whose death prevented his reputation from being defended in an equal manner.

So, what significant observations can be drawn from these orthodoxies?

Firstly, the historical assessment of Doctor Who is largely ideological, traced back to fandom, many of whom were of an impressionable age between 1975 and 1977 (Kilburn, 2010, p172). This ascribes ‘quality’ to ‘seduction’ and ‘pleasure’ rather than what makes it valuable in broader contexts (Caughie, 2000, p18).

Secondly, the emphasis on the pleasure of the critic results in an imbalance in how the analysis is expressed. If a constant narrative of Doctor Who centers on an appreciation for how it was made against the odds (Potter, 2007, p161-75), and that two producers defied many odds, the tastes of the reviewer will acknowledge the contexts that blighted Williams, without accounting for them in the final assessment. For example, rising inflation is referenced, yet a number of productions remain criticised for their cheapness (Traynier, 2019).

This connects to observations from Corner (2006), who notes that judgements are often tinted with can be described as a ‘personal phenomenology’, where readings are often judged for their qualities and meanings, ‘largely in relation to the views, predilections and insights of the critics themselves.’ In short, pleasure often defines the assessment. This is also reflected in established fan wisdom about Doctor Who, where the ‘undisputed truth’ is largely based on the perspective of what we see on screen, and in turn, connects to our feelings about it.

The notion of ‘value’ in television studies is hotly contested (Corner, 2006), often relating to social, industrial, and cultural values. Brunsdon (1990) noted the demotion of value in film and television studies, therefore removing broader public debates about film and television, such as ‘quality television’, moral and ethical arguments, and the political histories behind works (Brunsdon, 1990, cited in Caughie, 2000, p22).

So, while ‘value’ is explored within Doctor Who discourse, the established critical comparison between Hinchcliffe and Williams, suggests that this is secondary to ‘pleasure’.

This points to an opportunity to define ‘value’ for this thesis, and reassess the traditional orthodoxies of ‘good’ television in the case of mid-late 1970s Doctor Who. An example might be the challenges faced by Williams. Regardless of our own pleasure, what was the worth in repositioning the audience that Doctor Who was aimed at, over the risks in not changing the vision of the show?

Therefore, in the context of the eco-system of Doctor Who as an ongoing series, this thesis ascribes value as the result of creative innovation, experimentation, and risk-taking on producer vision. Innovation is a hallmark of quality and is essential in articulating the authored view of the producer, the longevity of the series, and the evolution of television production.

Chapter 2 – Innovation ‘out of the box’.

Before we identify models of innovation theory, it is important to ascertain a generalised, traditional model of making Doctor Who up to and including the mid-1970s.

Following the commissioning of a drama script by the BBC producer and/or script editor, pre-production planning would be initiated, with a director and other key members of the production team allocated. Once production was ready to commence, any exterior filming would be undertaken first, using 16 or 35mm film (McNaughton, 2014, p390-404). This was an expensive process in terms of ‘shooting ratio’, described (in this instance) as the number of minutes of transmitted footage recorded, versus the amount of time on location.

As an alternative to exterior filming, material might be filmed within a ‘four-walled’ interior such as Ealing Studios (then owned by the BBC). This used the same expensive process, but had the benefit of a more controlled environment. This mimicked how movies were made, capturing material not easily achievable within an electronic television studio, e.g., the use of water. Each shot could be lit, framed, and edited individually, offering greater opportunities for creative expression.

Fig 5. David Maloney. (1975) Filming on 16mm within a ‘four-waller’. Doctor Who – ‘Planet of Evil’.

Following this, most of the serial would be recorded on videotape within the multi-camera television studio, with performers acting on three-walled sets. Four or five cameras would be positioned, often across the ‘fourth wall’ (the audience’s viewpoint), to capture material simultaneously. The camera outputs were then fed to the production gallery, allowing the director to ‘call’ the shots – in effect, editing as live. This resulted in a shooting ratio that was far more economical than film, and characterised the ‘studio factory’ nature of mass television production – the multi-purpose BBC television centre (McNaughton, 2014, p391-394). Studio sessions or ‘blocks’ were often two to three days long, and recording would often take place in the evening, with a 10pm curfew, at which point the lighting would often be switched off, and production staff would ‘down tools’ under union rules and lines of demarcation (McNaughton, 2014, p15-17).

This generalised description highlights how the multi-camera approach was developed from theatrical aesthetics, rather than from cinematic film. Overhead lighting was fixed, cameras were limited in movement, there was care in ensuring microphones were not in shot, and editing lacked expression. With time being the determining factor, the multi-camera technique emphasised dialogue rather than action, and was known as a naturalistic aesthetic (Cooke, 2005, p82-99) based on the size of the television receiver, and that it was viewed by small households, rather than mass audiences (Swift, 1950).

By the 1960s, there was an increasing perception that multi-camera drama was a form that was restrictive in its creative and aesthetic potential (Kennedy Martin, 1964, p21-33), and that the potential for out-of-sequence recording could mimic the expressive ‘realism’ of film. (Cooke, 2005, p86).

The duopoly of BBC and ITV, resulted in direct competition for the audience’s need for information and entertainment. While competitive, there was financial stability for both institutions, increasing a spirit of innovation and risk-taking on the part of programme makers. This is reflected in a governmental paper, published in 1962. The Pilkington Report considered the impact of commercial television and encouraged the BBC to be less puritanical in its approach. The viewer was contextualised as a citizen, and the report took the view that television should be distinctive, have the power to care about, and offer the capacity to change public tastes and attitudes. Pushing boundaries and courting controversy became acceptable (Caughie, 2000, p128). The impact on the BBC was significant, with Sydney Newman, the new BBC Head of Drama, creating a culture of ‘producer power’, enabling ownership and empowering innovation. Crucially, there was a responsibility on the producer to signpost potential areas of controversy to their Heads of Department (Bignell, 2014, p7). This is significant, as we will discover.

The next governmental committee, the Annan Report on the Future of Broadcasting, was published in 1977, coincidentally at the point where Hinchcliffe was replaced by Williams. However, more significant to this thesis was the 1986 Report of the Peacock Committee, which emphasised economics over citizenship (BBC, 1986, cited in Transdiffusion, 2017). The report contextualised the viewer as a consumer, whose right to choose was the driving force behind a shifting industry. Peacock proposed a reduction of censorship within a free market context, giving the public what they want (Caughie, 2000, p82).

The freedoms and constraints that sit between the Pilkington and Peacock committees are significant and influence approaches to innovation and stylistic decision-making. Even by the 1970s, the BBC had to demonstrate ‘value for money’ (Hansard, 1969), and commercial television needed to ensure output that encouraged advertising revenue. In short, television was increasingly dictated by budget and turnaround. As Bignell (2014, p3) notes, television production in the 1970s was a discursive struggle between aesthetic and ideological motivations, and the resources and power needed to fulfil them.

Sitting within this struggle is the drive to innovate. While many theorists have identified creative drivers as fundamental to innovation such as culture, motivation, creative problem-solving skills, and expertise (Adams, 2005). Innovation theories are often positioned within the context of economics or capitalism, where ideas are developed to sustain a company. For example, a theory known as creative destruction, developed by Joseph Schumpeter (1942), regards innovation as the driver of economic growth, and is simply translated by recognising how something can become obsolete when something new replaces it.

Naqshbandi & Kaur, (2015, p41-51) similarly position innovation within business management, identifying several theories that consider the factors behind innovative thinking. The Diffusion of Innovation theory (Rogers, 1963) explores how an innovation might be adopted culturally, including contexts/systems, timeframes, and means of communication. The central argument is that sustained innovation is achieved when it is used widely within an organisation.

A widespread theory is Incremental (Sustained) Innovation. This theory is difficult to ascribe to one individual, but is articulated as the enhancement of what has gone before, without the immediate need to remove a preceding product or model. Prior knowledge is built upon in smaller and frequent intervals, thus keeping the market competitive (Naqshbandi & Kaur, 2015, p41-51).

In contrast, Radical Innovation is where established knowledge is very different from what is being developed, whether that be ideological or technological. The resulting product, service, or practice is so different from what has gone before that the preceding model becomes obsolete, even if the market remains (Naqshbandi & Kaur, 2015, p41-51).

Disruptive Innovation (Christensen, 1997, p23) proposes that innovations can create new markets that eventually replace old ones, resulting in an evolution of the technologies used and an improvement in the product or the service. For example, Naqshbandi & Kaur, 2015, p41-51) identify how the telephone replaced the telegraph.

Paradigm shifts and immediate changes characterise Breakthrough Innovation. Satel (2017) notes an example of how technology can play a role in detecting pollutants within an underwater setting:

We run into a well-defined problem that’s just devilishly hard to solve. In cases like these, we need to explore unconventional skill domains, such as adding a marine biologist to a team of chip designers.

(Satell, 2017).

These theories all relate, in some capacity, to the pace of change. However, in the light of Doctor Who, and the creative nature of television production, persona or character is important. While research conducted by Bendotti (2017) identified the influence of extroverted or introverted personalities on innovation, it is the attitudinal factor that is more significant. For example, in her article for The Royal Society for Arts, Billie Carn (2021) notes the characteristics of maverick innovation:

Mavericks challenge the status quo by questioning why we have to do things the way we have always done them, and because they believe there is a bigger, better, stronger, faster way. They ask ‘what if’ and ‘why not’, thinking differently and chasing audaciously big moonshot thinking goals.

(Carn, 2021).

From these theories, emerging themes can be identified. Creative Destruction and Disruptive Innovation are largely centered on the replacement of the old with the new.

Incremental or Sustained Innovation focuses on gradual change, building upon what has gone before. Radical, Disruptive or Breakthrough innovation theories are characterised by a distinct shift, change in technology, or in some cases a new market.

There are challenges of innovating within an ongoing commercial market or adopting change within an institution to remain relevant. The nature of Doctor Who – an ongoing television series made by an established broadcaster – requires innovation for it to remain relevant in the light of industrial and market forces. This provides an opportunity to consider how both producers innovated, and to shift the focus away from ‘established’ Doctor Who narratives and reasoning, in favour of an objective, industrially minded assessment.

Chapter 3 – Producer innovations

Hinchcliffe’s vision of enhancement was more pronounced with each of his three seasons, but the pinnacle was ‘The Deadly Assassin’ (Maloney, 1976), which subverted the traditional grammar of Doctor Who, while retaining the established methods of recording material.

The opening few minutes of the serial contain many innovative approaches to screen-based storytelling techniques: a roller caption that gives the background context to the story (a technique made famous by Star Wars the following year), the use of a ‘fish eye’ or ‘tunnel’ lens to depict the subjective view of the Doctor, and objective camerawork that foreshadows the events leading up to the end of the first episode.

The serial also uses creative elements: transitions, freezeframes, glass shots (a technique where settings are expanded by using artwork or photographic elements) ‘split screen’, (multiplying the number of supporting artists or ‘extras’), and an acknowledgment of the BBC’s own approaches to ceremonial events, by replicating a live news report, complete with hushed, and reverential commentator. (Boyce and Wiggins, 2020).

Fig 6. David Maloney. (1976) Subverting traditional television grammar in Doctor Who – ‘The Deadly Assassin.’

In many cases, these storytelling devices are not new; however, the innovative juxtapositions and concentrated use of these devices are brought into sharper focus when combined with an innovative narrative approach – the Doctor as a lone figure without the familiar companion. Suddenly, the audience is faced with the unfamiliar. Although this is a significant departure from the norm, this should be viewed as an incremental innovation, given that these new approaches are part of a culture of modest change, and were not adopted wholesale in the serials following ‘The Deadly Assassin’.

Another innovation was the decision to bring together costume and set designers to support a ‘unity of concept’ (Acheson, 2011) – an overall production design that connects different visual elements. This ambition to enhance production values can be evidenced through the boldness of the lighting and detailing of both set design and costume. The large split-level set that housed the ‘Panopticon’ was a logical progression of the work of Roger Murray-Leach, whose innovative pushing of vertical scale characterised Hinchcliffe’s era, and resulted in a third of the total budget of The Deadly Assassin being allocated to this ambition (Boyce and Wiggins, 2020).

Fig 7. Roger Murray Leach – examples of split-level set design. Doctor Who – ‘The Ark in Space’ (1975) and ‘The Deadly Assassin’ (1976)

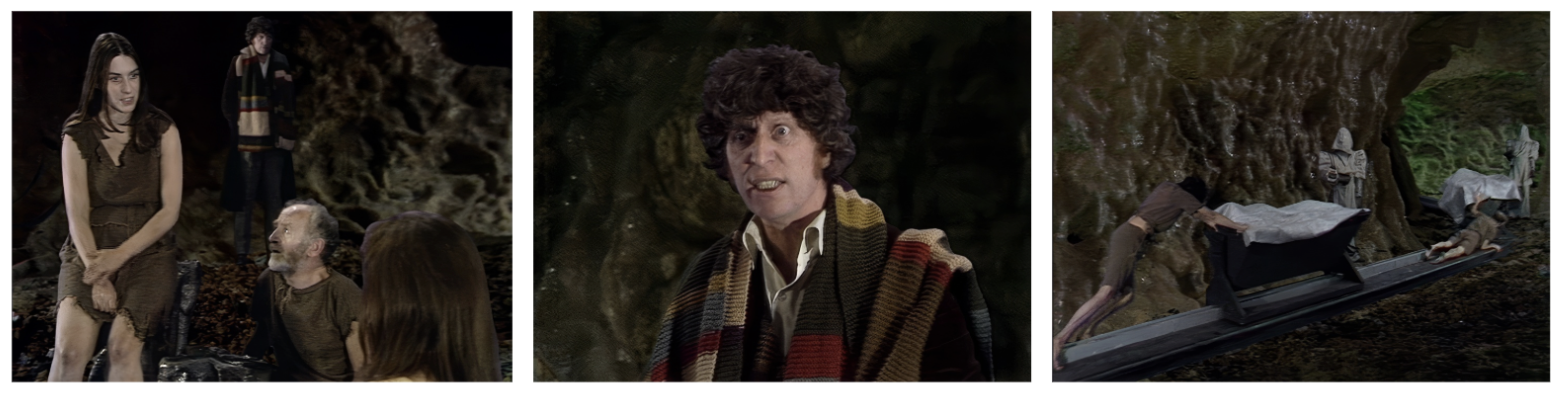

One of the most notable aspects of the four-part ‘The Deadly Assassin’ is episode three. This can be seen as an example of breakthrough innovation, where the fusion of storytelling devices and the method used to depict it, collide to create a radically new approach.

Writer Robert Holmes was conscious of the challenge of the third installment of many Doctor Who tales, where the story is fully established, yet isn’t close to being resolved, resulting in an episode that marks time (Boyce and Wiggins, 2020). Instead, Holmes creates an adventure that is distinct from the rest of the tale. The lack of a traditional ‘monster’ is replaced with a surrealist fight to the death between the protagonist and antagonist. By reallocating material that might have been recorded using indoor sets within the BBC’s Ealing Studios, the budget accommodated a five-day film shoot.

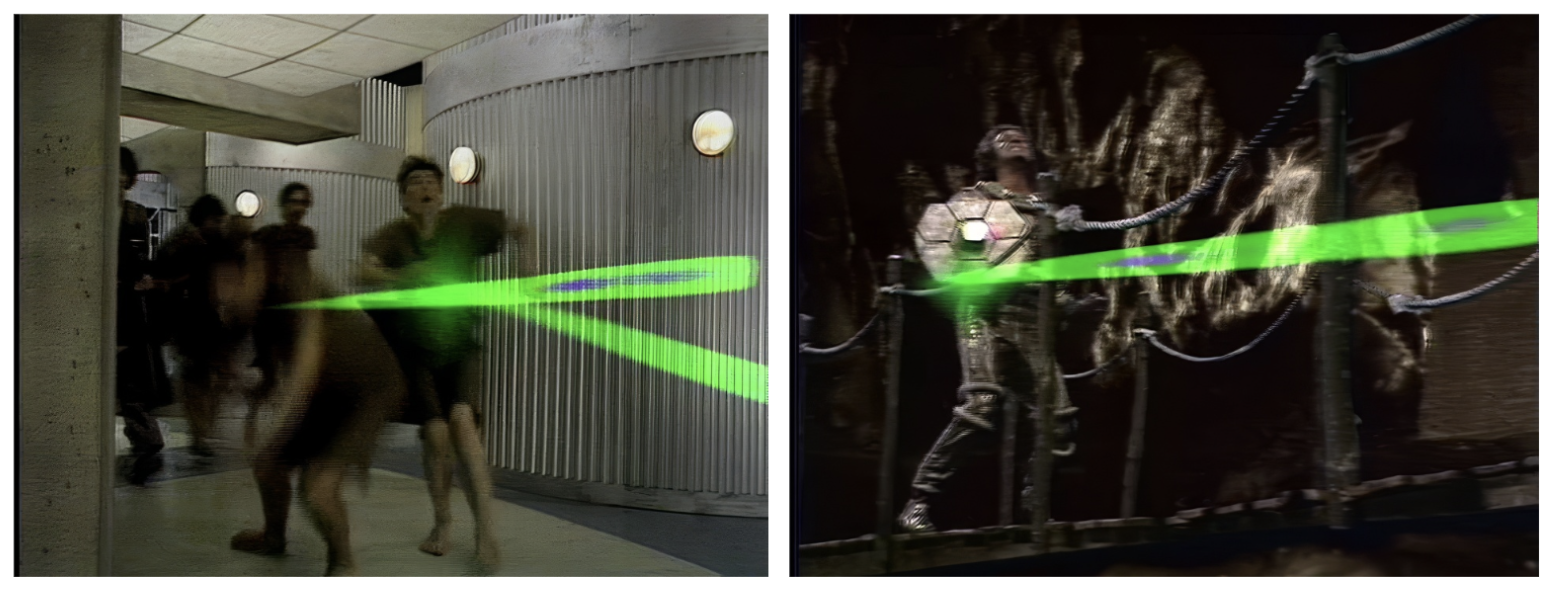

Fig 8. David Maloney (1976) – using film and surrealism to distinguish episode three from the remainder of the serial. Doctor Who – ‘The Deadly Assassin.’

The use of the single-camera method to film material, allowing each shot to be set up to the precise specifications of the director and to maximise the possibilities for editing later, results in a surreal and unsettling quality, heightening the dramatic and violent conflict that resulted in Mary Whitehouse claiming victory in her ongoing battle against the BBC.

This tension between established and innovative practice is at the heart of the conflict between Doctor Who and Whitehouse. Innovative practice is characterised by pushing the envelope, in this case, the BBC’s own editorial and production guidelines. Indeed, in her book Cleaning Up TV, Whitehouse (1967) uses the BBC’s code of practice as one basis of her mission. The guidelines warn against the use of shots that dwell upon gruesome aspects of combat, the emphasis on brutality, and the impact of the close-up.

Fig 9. David Maloney (1976) – pushing boundaries. Doctor Who – ‘The Deadly Assassin’.

With this in mind, it can be argued that ‘The Deadly Assassin’, and Hinchcliffe’s proactive approach is an example of radical innovation. The existing audiences and production techniques of Doctor Who are broadly retained. However, new approaches in their use are radically different enough to render previous Doctor Who eras as being ‘of their time’. In short, it is a significant leap forward.

The proactive innovations of ‘The Deadly Assassin’ are also characterised by maverick innovation. If we consider a definition of the maverick as independent, or someone who does not follow the conventions set by others, Hinchcliffe was successful in his aim to produce an experimental story that would ‘extend’ Doctor Who (Boyce and Wiggins, 2020).

To this end, he gave licence to writer Robert Holmes, and director David Maloney to be maverick in turn, pushing respective production boundaries. Holmes shared Hinchcliffe’s desire to proactively explore the unfamiliar areas of narrative, tone and production techniques, and to embrace the unexpected (Boyce and Wiggins, 2020).

‘The Deadly Assassin’, acts as a marker in using production techniques differently, particularly through its liberal use of film, resulting in it being one of Hinchcliffe’s more expensive productions. These innovations in production methods are amplified later in the season through the allocation of film and video in ‘The Talons of Weng-Chiang’ (Maloney, 1977). For this serial, Hinchcliffe swapped the standard three-day studio recording with an outside broadcast (OB) unit on location. Instead of time-consuming shooting single-camera film, various locations in Northampton became the location of a multi-camera shoot, allowing for more footage to be recorded, making up for some of the lost studio time. (Wiggins, 2020).

Fig 10. David Maloney (1977) – allocating film to enhance production values. Doctor Who – ‘The Talons of Weng-Chiang’.

It is easy to describe Hinchcliffe as a maverick, but to justify whether this is fair, it is worth considering the culture and expectations of the BBC producer.

As previously identified, the 1962 Pilkington report resulted in increased freedoms for BBC producers, with any controversial avenues being reported to their head of department. Although the revolving door of Doctor Who producers had always necessitated a close relationship with their superiors, Hinchcliffe seemingly benefited from this approach and enjoyed relative freedoms in terms of pushing boundaries, as long as he was delivering the programme that had been commissioned (Hinchcliffe, in Vanezis, 2020).

‘The Deadly Assassin’ was not only well received by the public through high viewing figures, but also by the BBC itself, with senior executives ‘warmly commending’ the first episode following an internal review. (Boyce and Wiggins, 2020). In short, Hinchcliffe was delivering.

Conversely, there were further consequences arising from the serial. Costume Designer James Acheson left the production citing burnout due to prior accumulated pressures, but also a lack of time and money, and a sense of awe of working with someone who was full of ‘creative energy’ as Marray-Leach, (Acheson, 2011).

It is therefore interesting to note the tensions between freedom and responsibility. Towards the end of Hinchliffe’s run, there were concerns voiced about overspending, disputed by Hinchcliffe (2024, p153). Christopher D’Oyly John (1996) acted as Hinchcliffe’s Production Unit Manager, a role that placed emphasis on financial management. He noted that Hinchcliffe ‘never cut back.’ This expands upon an observation made by his predecessor George Gallaccio (1999) that Hinchcliffe didn’t know the BBC system, thereby bypassing a degree of responsibility and suggesting that Hinchcliffe might have been getting away with it due to the results on screen and strong audience figures.

Considering Hinchcliffe’s assertion that he never pushed boundaries irresponsibly (Jeffery, 2021) the evidence points to a producer approach that was a cultural expectation, with risk-taking accepted as de rigueur. In the case of his later serials, it resulted in admirable output on screen, arguably at the expense of longer term sustainability.

Within fandom, the narrative innovations of ‘The Deadly Assassin’ resulted in a backlash in some quarters. Sweet (2024, p26) notes a jarring between the progression of a show, and the reverence of historical continuity, as articulated by Vincent-Rudzki, (1977). This view of ‘The Deadly Assassin’ softened as the appreciation for the Hinchcliffe era solidified.

If the innovations seen within ‘The Deadly Assassin’ pushed the envelope from a solid base, the tail end of Graham Williams’ first season in charge saw innovations developed to simply keep Doctor Who in production.

As already established, both producers inherited a very different show from their predecessors, shaping their initial approach and, subsequently, flavouring their critical reputation. Hinchcliffe’s drive for enhancement and Williams’ questioning of Hinchcliffe’s approach suggest a drive for innovation that was both proactive and reactive in nature. Both acknowledged their predecessors and wanted to make their mark.

Whereas Hinchcliffe talked of peril, plotting, and cliffhangers (Jeffery, 2021), Williams devised a highly conceptual hypothesis to demonstrate that he could bring and implement new ideas to the show. (Williams, 1992). By painting Doctor Who on a broader canvas, centered around the delicate balance of the universe, the idea became the basis of Williams’ second season, a series of six stories. In establishing a new framework that is radically different from what has gone before (including how The Doctor operates within the universe), some new elements of the series’ DNA render previous thinking obsolete. Therefore, the story arc is both an example of radical and maverick innovation, where the status quo of the series structure is questioned by asking ‘what if’ and ‘why not’. This starts to challenge the assumption that Williams was a ‘dove’.

The first Williams story to go into production also demonstrated a nous of the screen landscape and means of enticing new audiences. Few assessments of Williams omit K9, a computerised robot dog, the like of which had not been seen in Doctor Who up to that point. This coincided with the release of Star Wars, (Lucas, 1977), raising both audience expectations and marketing opportunities of science fiction (Duckworth, 2021, p51-59).

A move towards a younger viewership, it was initially suggested that K9 was operated by a human from within, as had worked so successfully with the Daleks (Williams, 1984). Williams argued against this, recognising the potential of the character in terms of commercial exploitation, and attempted to work with the commercial arm of the BBC to fund the design of something compact enough to be operated by remote control. Despite the operational challenges of K9 within the television studio, the character was popular with the audience and is an example of breakthrough innovation, where the creativity of writers and visual designers, combined with commercial thinking, resulted in a distinctly new outcome.

Fig 11. Tony Harding (1977) – Production documentation capturing initial design concept for K9.

Despite K-9’s popularity, a production memo, (Bignell, 2024) sent by Williams to his superior highlights how the investment in developing this innovation did not yield the rewards from the potential commercial and merchandising exploitation of the character. There is a determination in Williams’ language, noting the gamble he took, and how the success of the character, borne from the investment he authorised, should be recognised through a greater return, thus benefiting the show. This demonstrates that innovation can be a proactive endeavour, even when responding to reactive contexts (the need to counter the approach of his predecessor).

Fig 12. Graham Williams (1977) – BBC memo from Graham Williams to his Head of Department.

The critical assessment of Williams’ era often identifies budgetary restrictions and a decline in production values. The yearly budget for Doctor Who was set at the beginning of the production block for each season. In 1976, the UK was affected by hyperinflation (Bogdanor, 2016). The difference in economic circumstances marks a divide between the two producers. Hinchcliffe benefited from some of the largest real-term budgets afforded to a BBC producer during the show’s original run (Boyce and Wiggins, 2020). Consequently, his era’s reputation is linked to the show’s high production values (Muir, 2007, p256).

In contrast, Williams took over the show the same month an IMF loan was agreed, resulting in three years of budgetary reductions amid national and industrial crises. Money was controlled tightly, meaning that overspending (a luxury enjoyed by Hinchcliffe) was not available to Williams (Williams, 1990). As 1977 progressed, the rampant inflation rates resulted in a depreciation of the money available.

Although evident in some transmitted material, a decline in production values is too singular an argument, as it neglects Williams’ ambitious innovations, achievements, and developing stylistic tone.

An example of this is ‘The Sun Makers’ (Roberts, 1977) – a satire of the tax system on the citizens of Pluto. The story opens within a largely featureless corridor, which further reduces the characters within a world devoid of stimulus and humanity. This production was beset by budgetary restrictions, and the removal of fantastical elements supports the broader common assessment of a ‘lacklustre’ design, with Graham Williams being unable to inspire the creative production personnel within the BBC (McGown, 2023, p49). However, the set design can also be viewed as an artistic decision, emphasising viewpoint over production values (Owen, 1990).

Connections can be made with the single play ‘Psy-Warriors’ (Clarke, 1981), cited as a production that uses artistry to create a space, rather than photographing a stage (Rolinson, 2014.) Here, bright lighting, the relationship between foreground and background, and the sparse mise-en-scene evoke themes of sensory deprivation and force the audience to consider what we are observing, and where we are observing it from (Rolinson, 2014). Coincidentally, two differing perceptions illustrate the acceptance of artistry within the prestigious single play, but not the popular, ongoing series.

Fig 13. Pennant Roberts/BBC (1977). Doctor Who – The Sun Makers.

Fig 14. Alan Clarke/BBC (1981). Psy-Warriors

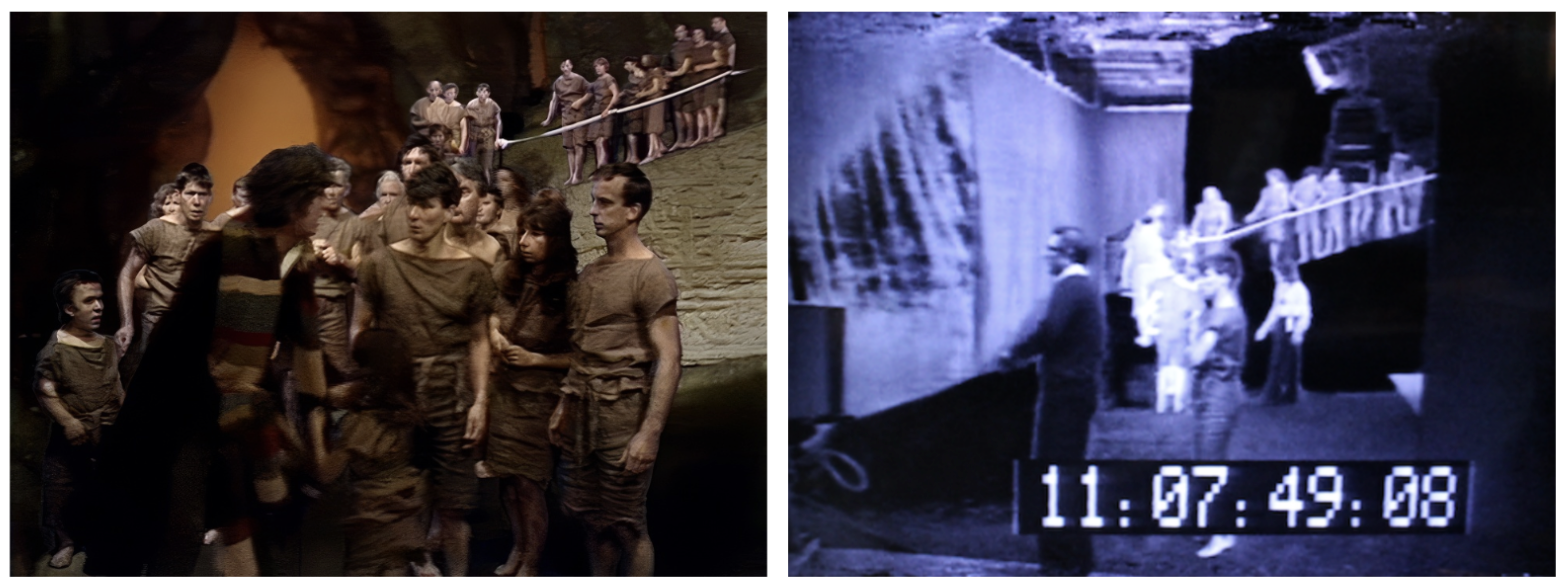

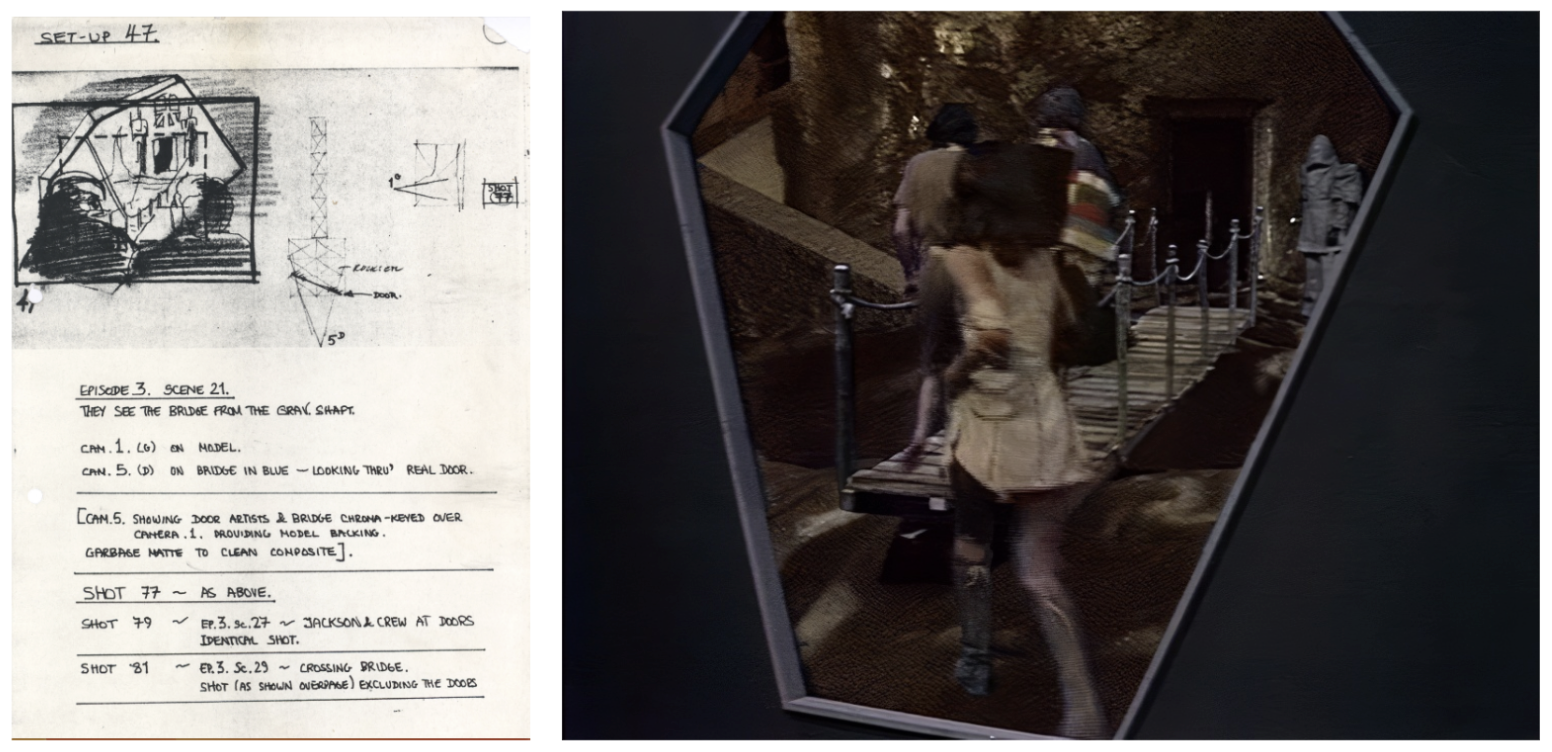

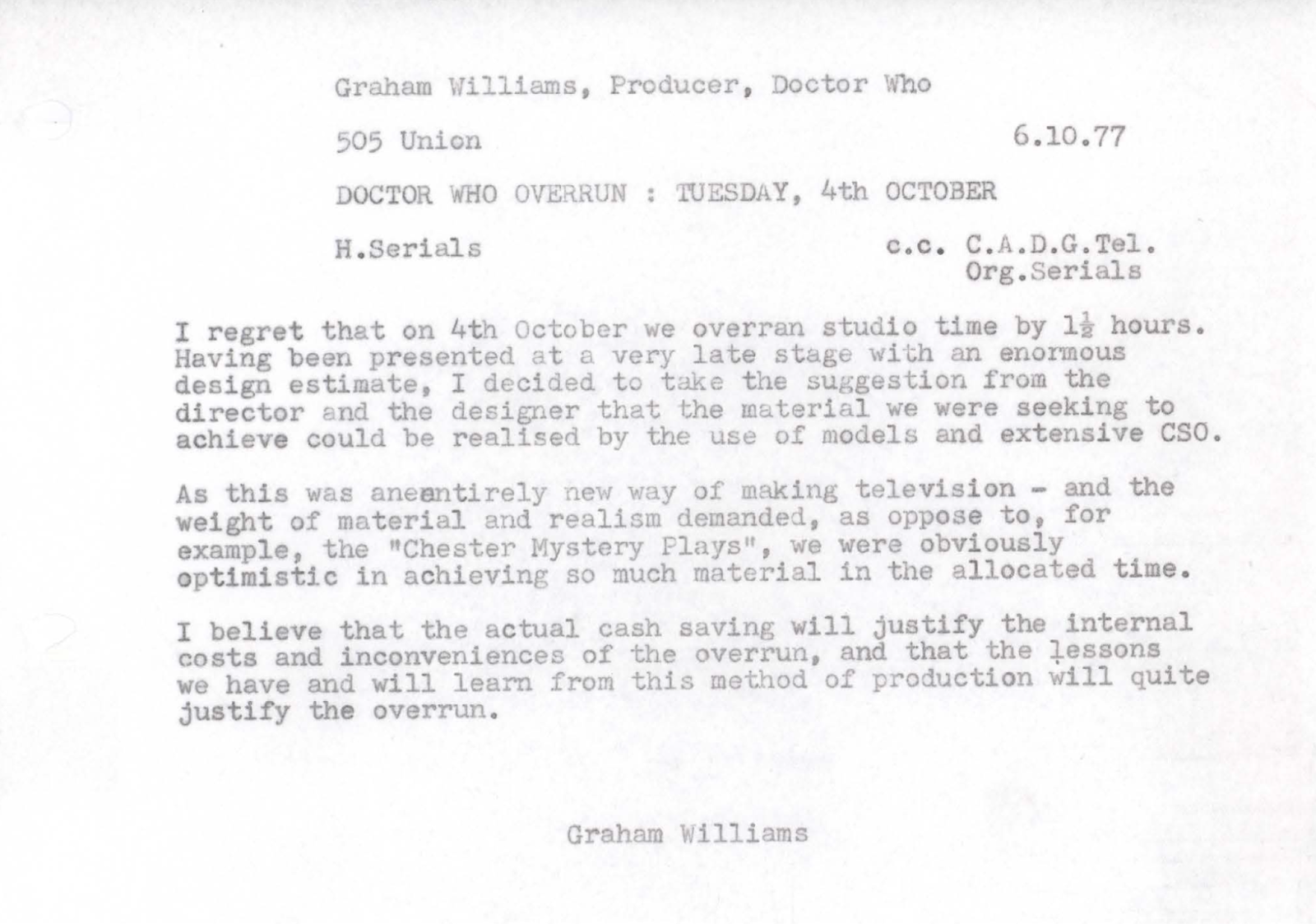

Budgetary contexts shaped the development of ‘Underworld’ (Stewart, 1978), the fifth story of Williams’ first season. A financial shortfall resulted in no money for all the set designs required. An alternative was to use the blue screen technique – Colour Separation Overlay (C.S.O).

Fig 15. Norman Stewart/BBC (1978). Comparative shots from Doctor Who – Underworld.

Using C.S.O. to this extent required collaboration that far exceeded typical departmental knowledge and practice. The director Norman Stewart (alongside Graham Williams) placed faith in electronic effects designer A.J. Mitchell to deliver the results, far beyond the traditional hierarchy between the director and their production team.

Personal testimonies recall the all-night set-ups and meetings between various Heads of Department (Mitchell, 2010) and how the upheavals involved split BBC personnel along the lines of traditionalists and boundary-pushers (Read, 2010). This references the diffusion of innovation theory (Rogers, 1963) and the battle to embed new cultures. The risks were mitigated and assurances achieved through highly detailed storyboards that allowed a clear understanding of what was required. And once ‘bedded in,’ the C.S.O. process became easier to achieve during the remainder of the production, resulting in the extraordinary becoming culturally accepted.

Fig 16. A.J Mitchell/Norman Stewart/BBC (1978). Storyboard and frame from Doctor Who – ‘Underworld’.

Panos (2013, p14) notes that C.S.O. was a counterpoint to the traditions of naturalistic drama. A number of dramas used the technique to create visually distinctive outputs and different modes of realism. It appears particularly suited to fantasy. Doctor Who already incorporated the fantastical, so the use of C.S.O. was largely to enhance expressive modes of storytelling or expand the opportunities for world-building.

Fig 17. Norman Stewart/BBC (1978). C.S.O as storytelling device. Doctor Who – ‘Underworld’.

However, given the contexts that surrounded ‘Underworld’, this serial might be the ultimate expression of C.S.O. in Doctor Who; offering fantastical world-building, but also using the technique pragmatically to depict environments and enhance action.

Fig 18. Norman Stewart/BBC (1978). Pragmatic use of C.S.O. Doctor Who – ‘Underworld’.

This is another illustration of how innovation can be conceived from a series of limitations, with the resulting output being both economical and artistic.

‘Underworld’ underran, albeit within acceptable parameters for transmission. Production scripts identify fewer shots than a typical Doctor Who episode, with C.S.O reducing the amount of footage recorded on a given day from 20-25 minutes per day (Williams, 1984) to one minute of footage per hour (Mitchell, 2010). This results in a slower pace, with scenes constructed by using longer or repeated camera shots. Scenes used elsewhere attempt to disguise repetition by using the same setup with minor modifications (Cooray-Smith, 2024).

Although placing great demands on cast and crew, ‘Underworld’ is a prime example of breakthrough innovation, bringing together different departments and fields of knowledge to achieve something new. The electronic video effects team not only benefited from Williams’ proactive approach, but also were able to demonstrate their strengths and ambition within a culture that eschewed hierarchy, in favour of collaborative cooperation and mutual trust.

Indeed, the rapid promotion of technically-minded Norman Stewart from production assistant to director can be viewed as an example of reactive innovation, as Williams was forced to find new directors, writers, and designers, due to many key crew members working on the BBC’s other ongoing science-fiction series, Blake’s 7 (Duckworth, 2021, p51-59).

Fig 19. Graham Williams/BBC (1977) – BBC memo from Graham Williams to his Head of Department.

In a production memo, Williams argued that the lessons learnt justified a financial overrun. Given the number of studio days and the minutes of material required to complete a story, it is remarkable that this breakthrough innovation between different disciplines resulted in the sheer amount of footage that allowed ‘Underworld’ to come in on time and on budget, even if Williams lamented its quality (Williams, 1990).

And it is this perception of quality that is the hallmark of the serial’s critical reception within fandom, suggesting ‘dull’ (Traynier, 2019) or ‘leaden’ (Martin, 1990). This is at odds with personal determination, sizable viewing figures, and the value of the innovations, which as a side note, also introduced a new policy, instigated by Williams and adopted by the BBC, known as a ‘gallery-only day’, allowing electronic effects teams to achieve a better result by utilising the studio production gallery when not in use. This resulted in more sophisticated and accurate results. (Mitchell, 1990).

Fig 20. Norman Stewart/BBC (1977) – accurate effects in Doctor Who – ‘Underworld’.

Even though Doctor Who did not use C.S.O. on this scale again, there were numerous values to innovating in this way. For example, experimental equipment was used to reduce the ‘fringing’ seen around the edges of superimposed actors – a common consequence of this process (Mitchell, 2010). Also, ‘Underworld’ tested synchronous foreground and background movement, foreshadowing the ‘scene-synch’ technological development used three years later in ‘Meglos’ (Dudley, 1980).

Fig 21. Terrance Dudley/Renny Rye/Norman Stewart/BBC. Evolution of C.S.O capabilities in Doctor Who – ‘Underworld’ (1977), Doctor Who – ‘Meglos’ (1980) and The Box of Delights (1984.)

Given widespread C.S.O. use across BBC television programmes, these innovations benefited BBC dramas in the future. Therefore, ‘Underworld’ is an exemplar of an innovative creative ecosystem surrounding the production of Doctor Who, to support its longevity.

Reactive innovations characterise the following serial ‘The Invasion of Time’ (Blake, 1978.) An industrial dispute reduced the normal studio allocation required for a six-part Doctor Who story. This was usually broken down into six days of location on film, and six days of video recording in the studio (Wiggins, 2023). In addition, the script that arrived (from a writer with no previous Doctor Who experience) was too ambitious for the resources and the production techniques that the series utilised.

Instead of abandoning the serial, Graham Williams and Anthony Read (script editor) rapidly crafted a new tale. Use was made of a BBC ‘strike fund’ (Pixley, in Ainsworth, 2017), allowing the use of a multi-camera outside broadcast (OB) video unit. A disused asylum in Redhill, therefore, acted as a proxy television studio, with space for the performer, lighting, sound, and set elements. The multiple cameras were fed into a vision mixer – a device allowing a director to select the shots (and therefore edit ‘on the fly’), and to integrate electronic effects appropriately. Although more footage per minute could be recorded using the multi-camera process than single-camera film, location work was more time-consuming than the BBC electronic studio. Therefore, Doctor Who was granted 18 production days, instead of the traditional 12 (Wiggins, 2023).

One of the first instances of extensive OB in drama is Hamlet at Elsinore (Saville, 1964) – recorded in Denmark – where it was noted that director Philip Saville achieved an aesthetic closer to the naturalistic studio drama than the ‘realism’ of film (Cooke, 2005, p87). This is also evidenced in ‘The Invasion of Time’, where the grammar of continuous action and use of video to suggest an interior setting, mimics traditional studio language.

Fig 22. Gerald Blake/Philip Saville. Naturalistic grammar on videotape. Hamlet at Elsinore (1964) and Doctor Who – ‘The Invasion of Time’ (1978)

This benefited an ongoing series like Doctor Who, where OB was used largely proactively, and as a mode of enhancement, acting as a viable way of making full use of an otherwise unviable location. This resulted in the show’s first ever all-location shoot, on Dartmoor, for ‘The Sontaran Experiment’ (Bennett, 1975) and the use of a Victorian Theatre in Northampton, for ‘The Talons of Weng-Chiang’ (Maloney, 1977) both enhancing the dramatic potential of exterior locations.

Fig 23. Rodney Bennett/David Maloney/BBC. Videotape as a means of enhancing location possibilities. Doctor Who – ‘The Sontaran Experiment’ (1975) and Doctor Who – ‘The Talons of Weng-Chiang’ (1977).

While the allocation of OB in ‘The Invasion of Time’ was not an innovation per se, it was part of a production process used innovatively to overcome an institutional demand. However, the use of it can be seen as an example of incremental or sustained innovation, tapping into an increasing trend of television dramas being shot on video, (the apocalyptic 1970s BBC drama Survivors is a case in point). The improved shooting ratio reduces the dependency on the television studio, (Hinchcliffe, 2024, p51). Also, the capabilities of the OB unit are pushed beyond traditional use. Electronic and visual effects, C.S.O., and the opportunities of the location (extending the scale of the traditional Doctor Who corridor) are different requirements from the conventional use of OB for live events, or sporting coverage.

The use of videotape in ‘The Invasion of Time’ paves the way for a more stylish use of OB in Doctor Who the following year, with ‘The Stones of Blood’ (Blake, 1978) using filters, and inventive directorial touches, predating the opportunities Doctor Who will exploit towards the end of its life-span in the mid-late 1980s.

Fig 24. Darrol Blake/BBC. (1978). Stylistic use of videotape. Doctor Who – ‘The Stones of Blood’

Reviewing the transmitted material from ‘The Invasion of Time’, it is interesting to consider that while it was made under reactive and challenging circumstances, it does not compromise on the vision of Doctor Who as set out by Graham Williams, who was concerned by the previous depiction of Time Lord society on Gallifrey.

Stylistically speaking, in Hinchcliffe’s ‘The Deadly Assassin’, Gallifrey is depicted as dark and shadowy, with gothic, feudal, or mediaeval sensibilities, whereas ‘The Invasion of Time’ is somewhat ‘G-plan’ (Pegg, 1990), being more illuminated, and containing an array of modernist and postmodernist artifacts. This is a conscious decision, and as Pegg notes, one that not only characterises Williams’ eclecticism and intellectualism but also debunks the vision established during the Hinchcliffe era, in turn, debunking what had gone before. Interestingly, the ‘G-plan’ aesthetic is influential, also shaping future depictions of Gallifrey during the 1980s.

There are differences in the sequencing of the two serials. Whereas ‘The Deadly Assassin’ plays with visual effects and transitions, ‘The Invasion of Time’ uses dialogue to juxtapose consecutive scenes, such as different characters saying the same lines with different emphases. The amplification of witty dialogue is a hallmark of the Williams era.

VARDANS: He understands discipline. Cut to. BORUSA: ‘No discipline, that’s always been the trouble’

Fig 25. Gerald Blake/BBC (1978). Doctor Who – ‘The Invasion of Time’.

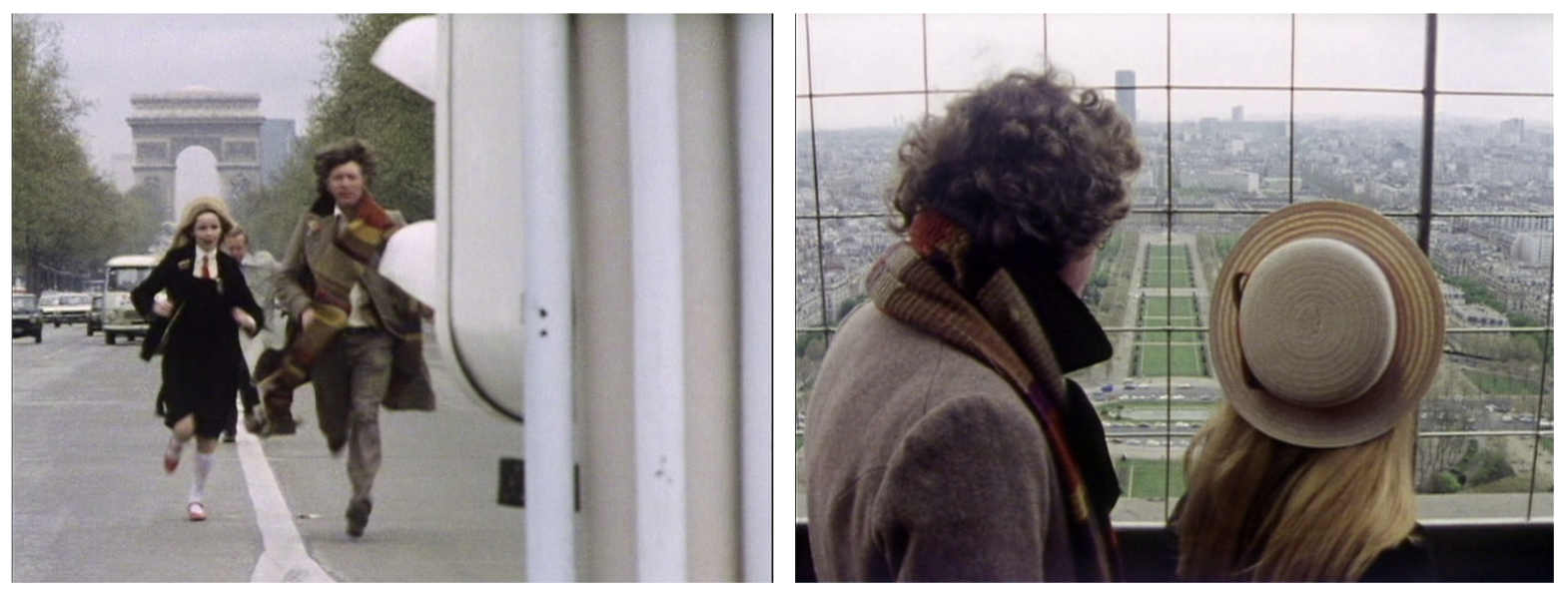

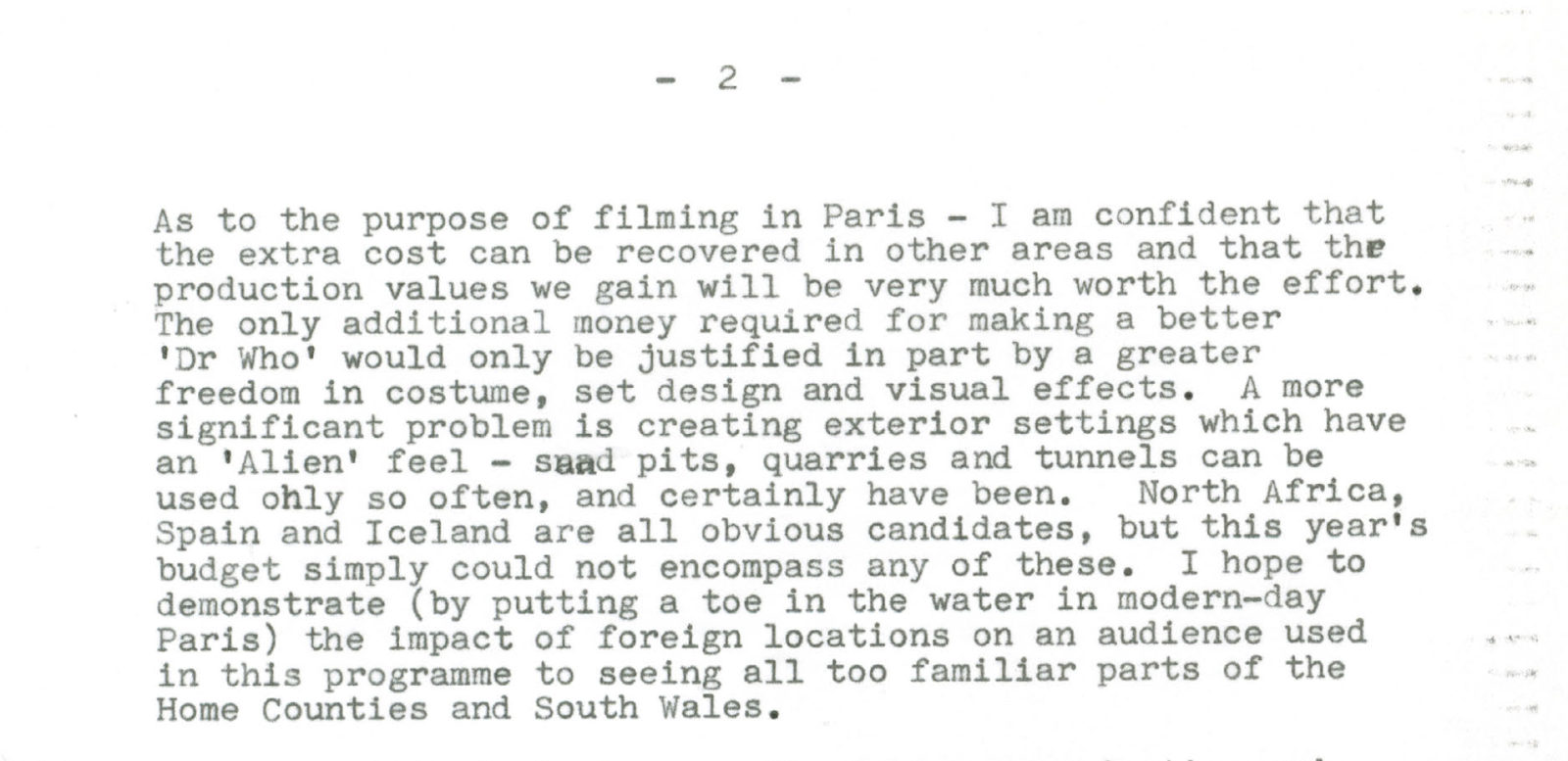

In terms of breaking through budgetary limitations, Williams was responsible for Doctor Who’s first overseas trip (Wiggins, 2021). The common narrative centers around how Williams worked with his finance-conscious Production Unit Manager to explore how budgets and resources could be shifted to accommodate a modest film shoot in Paris.

Fig 26. Michael Hayes/BBC (1979). On location in Paris. Doctor Who – City of Death.

It is interesting to note Williams’ proactive approach and the resistance of his line-manager, the Head of Series and Serials, Graeme MacDonald. The impact of Star Wars is felt, with a concern that overseas filming was an extravagance and could lead to difficulty in justifiably asking the BBC for ‘more money for better sci-fi effects’. Williams argued that international filming was a ‘toe in the water’ and could lead to further, more expensive location forays (Bignell, 2021). This suggests disruptive innovation, where allocating funds differently leads to developments in sustainably shooting Doctor Who. It is also maverick, with Williams challenging the status quo, and once again accentuating the strengths of Doctor Who when the production values of Star Wars heightened audience expectations (Wiggins, 2021).

The exchange is also a hallmark of the difference between the relationship between the producer and head of department, who is increasingly aware of ‘value for money’, tipping the scales from the freedoms of the Pilkington committee, towards the economies of the Peacock committee.

Fig 27. Graham Williams/BBC (1979) – BBC memo from Graham Williams to his Head of Department.

The evidence in this chapter points towards the importance of producer vision. If, in cinema, a film director might be accorded auteur status, with an emphasis on the ability to translate script to image, it is the scriptwriter who is seen as bringing prestige to the screen within television (Caughie, 2000, p128). The writer writes, the script editor shapes and codes, and the director interprets. However, it is the producer who oversees the entirety of this process, becoming the architect of the series (Tunstall, 1993, p119) and by doing so, expresses a style and vision.

Both producers had a clear vision that embraced ‘catalysts’ – the adaptation of existing sources from literature and cinema (Wollen, 1969, p576). These became ‘agents’ that reacted with the themes and characteristics of the producer’s vision and style, resulting in radically new work. Therefore, Williams’ broad eclecticism and architectural frameworks, and Hinchcliffe’s focus on atmosphere and quest for enhancement, react with Hinchliffe’s use of gothic and psychological horror, and Williams’ eclectic flights of fantasy. This becomes more than the retreading of old influences, but inherently innovative modes of articulating their own producer vision, elevating them into the producer equivalent of the auteur.

Conclusions

Firstly, the handover from Hinchcliffe to Williams is not simply a Mary Whitehouse-influenced turning point in Doctor Who, but can be read as a marker of an evolving industry, notably the intersection of two governmental papers of the early-1960s and the mid-1980s. There is a connection between the Hinchcliffe era and the Pilkington report of 1962, positioning the viewer as a citizen, giving producers freedom to take risks. The other connection is between the Williams era and the Peacock Committee of 1986, positioning the viewer as a consumer, reflecting a shift in the industry away from the anti-theatrical and contemporary, towards a business ethos with increased emphasis on ratings. The economies of the era, an increasing emphasis on value for money, and a producer increasingly scrutinised and regulated by departmental heads, all reflect a slow sea-change from the mid-late 1970s onwards.

Secondly, by analysing evidence through the lens of innovation theory, it is apparent that neither producer was more proactive or reactive than the other. Both innovated throughout their era, and always to emphasise their own producer vision. This is especially true within ‘Underworld’, where the restrictions imposed resulted in innovations that ensured that Williams’ broader vision of Doctor Who was not diluted. What did change was the contexts that these innovations sat within, with both producers equally and actively responding to the conditions in which Doctor Who was made.

This connects to a third conclusion – that the impact resulting from proactive or reactive innovations does not necessarily amount to different levels of ‘quality’. Both producers identified a need for change and evolution to the long-running format. Hinchliffe’s desire to nudge the formula, and Williams’ 15% refinement season by season, reflect an understanding of the television industry and audiences, but also acknowledge authorship and distinctiveness – often categorised as a producer ‘era’. Williams favoured character, situation and plot over hardware, production values, and set-piece (Cull, 2006, p61), indicating an awareness of the system, and calculating what difference it can handle at any given time (Caughie, 2000, p131). Indeed, Doctor Who remained popular in terms of viewing and audience appreciation index figures, through both producers’ eras (Sandifer, 2014, p135).

This allows us to consider the critical orthodoxies of Doctor Who – in particular, the reputation between Hinchcliffe and Williams, which is often competitive, favouring one over another, and largely in favour of Hinchcliffe. If this is based on an established mode of screen-based criticism, where the pleasure of the critic when reading a text is more important than the value it offers, it demotes important explorations about how Doctor Who was produced and assessed. By exploring both producers through an industrial ‘value’ based perspective, and reflecting the very different contexts behind their producership, it is possible to question the hierarchical comparisons (i.e, one was more successful than the other).

It can be concluded that Williams’s reputation is determined by fan pleasure, at the cost of his own evolving defense, and that of the value he offered. He needed to demonstrate proactivity within a reactive context – inheriting a series under increased scrutiny, requiring tonal change, an unsettled cast, and a need to recruit new directors, designers, and writers. While Williams’ concern over the content of ‘The Deadly Assassin’ aligned with his own vision of the show, his reputation as a weaker producer is amplified by BBC interventions to not only edit out violence, but to clean it up entirely (Williams, 1990). This reflects the sensitivity of the BBC from that point onwards, rather than Williams’ own lack of experience.

This is important in that it returns to an earlier point – the circumstances that Williams faced are often acknowledged within critical commentary, but are rarely accounted for in the overall assessment, due to pleasure being the dominant voice in critical discussion.

It can be concluded that Williams was as determined and ambitious a figure as Hinchcliffe. Williams sought novel innovations and solutions, at odds with the challenging industrial contexts he faced. He had a firm philosophy about breaking new ground, arguing that Doctor Who cannot sit still otherwise it will ‘die on its feet’ (Williams, 2006, p182), and held as distinct a vision for the show as Hinchcliffe. However, critical orthodoxies can be shaped by perspectives from Williams’ own production team, who offer a more defensive commentary on innovation, centred on crisis or misguided aspiration, such as ‘flying by the seat of our pants’ (Read, 2010) or ‘we always wanted to fly before the industry could walk’ (Read, 1991). This positions innovative practice apologetically, rather than as a positive evolutionary concept, and may partially account for how these views are critically interpreted.

By viewing producership through an innovative lens, there are opportunities to question Doctor Who as ‘neutered’ following ‘The Deadly Assassin’ (Sandifer, 2013, p201), and criticism of Williams. Hinchcliffe’s reputation is based on enhancement – a strong personal vision combined with the inheritance of a stable and popular series. While critical assessment is based on the appreciation of his work, accounts suggest there were consequences arising from his innovative approaches, both small-scale and long-term.

This supports the conclusion that Williams and Hinchcliffe – BBC producers, for whom ‘the buck stops here’ – were equally responsible for a range of dynamic innovations, or examples of innovative practice, that far belie the difference in critical reputation within fandom.

Overall, I would argue that innovative practice sits within the tension between the artistry (the subverted grammar of television drama, drawn from theatrical language) and the economic demands of the electronic medium. Pushing the envelope suggests the need for boundaries to support ongoing evolution (Hanchett, 2015, p371). It’s apparent that the economic methods of producing television – the ‘studio factory’ model – became the opportunity to push innovation, with proactive and reactive innovations equally required to sustain the series.

Doctor Who falls in the middle of these two perspectives, being both a serial recorded using economical methods due to the risk that its fantastical remit runs the risk of perpetually exceeding its budget, and being artistic due to the eclecticism of its own format. The boundary-pushing and artistry become the means of survival as a continuing series. This suggests that the demise of Doctor Who as an ongoing ‘in-house’ videotaped BBC drama is connected to the redundant multi-camera drama form, alongside the artistry/innovation connected to it, in the early 1990s.

However, the value and impact of these innovations are felt far beyond the era in which they were made. What is often quoted by many contributors who worked with both producers is that their work on Doctor Who acted as a training ground, allowing them to refine and develop their practice. That many people furthered their careers in the screen industry, or were awarded BAFTA and OSCAR nominations for their work, can be traced back to their innovative practices and the producers’ permission to innovate. And those who derived pleasure (or otherwise) from the ‘old favourites’ – a series that continually innovated – grew up to be more than what Hills (2010, p102-103) notes as the audience identity known as ‘fandom’, but as industry professionals responsible for modern-day Doctor Who.

Fig.28. Nick Hurran/BBC (2013) – The Day of the Doctor. But just… the old favourites, eh?

List of illustrations

Fig 1. Lodge, B., (1974) Doctor Who (Title Sequence) [online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00vd4t5/doctor-who-19631996-season-12-robot-part-1 [Accessed on 04/05/2017]

Fig 2. Maloney, M., (1976) Doctor Who – The Deadly Assassin [online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00vf7qz/doctor-who-19631996-season-14-the-deadly-assassin-part-3?seriesId=p0ggwr8l-structural-14-b0117993 [Accessed on 08/06/2025]

Fig 3. Cash, T., (1976) Whose Doctor Who? [online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episodes/p0gm238z/whose-doctor-who [Accessed on 08/06/2025]

Fig 4. Chapman, C., (2024) Introduction to ‘Darkness and Light – The Life of Graham Williams’ British Film Institute. February 8, 2024 [online] Available at https://x.com/ChrisChapman81/status/1754167157955412199 [Accessed on 08/06/2025]

Fig 5. Maloney, M., (1975) Doctor Who – Planet of Evil [online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00vf1w2/doctor-who-19631996-season-13-planet-of-evil-part-1 [Accessed on 08/06/2025]

Fig 6. Maloney, M., (1976) Doctor Who – The Deadly Assassin [online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00vf7gj/doctor-who-19631996-season-14-the-deadly-assassin-part-1 [Accessed on 08/06/2025]

Fig 7. Maloney, M., (1976) Doctor Who – The Deadly Assassin [online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00vf7gj/doctor-who-19631996-season-14-the-deadly-assassin-part-1 Bennett, R., (1975) Doctor Who – The Ark in Space [online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00vd56f/doctor-who-19631996-season-12-the-ark-in-space-part-1 [Accessed on 08/06/2025]

Fig 8. Maloney, M., (1976) Doctor Who – The Deadly Assassin [online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00vf7qz/doctor-who-19631996-season-14-the-deadly-assassin-part-3 [Accessed on 08/06/2025]

Fig 9. Maloney, M., (1976) Doctor Who – The Deadly Assassin [online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00vf7qz/doctor-who-19631996-season-14-the-deadly-assassin-part-3 [Accessed on 08/06/2025]

Fig 10. Maloney, M., (1976) Doctor Who – The Talons on Weng-Chiang [online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00vf9f1/doctor-who-19631996-season-14-the-talons-of-wengchiang-part-1 and https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00vf9kx/doctor-who-19631996-season-14-the-talons-of-wengchiang-part-3 [Accessed on 08/06/2025]

Fig 11. Bignell, R., (2024). Screenshot of design concept for K9, by Tony Harding. “Doctor Who – The Collection. Season 15 – Production Documentation” BBC Studios. Blu-ray.

Fig 12. Bignell, R., (2024). Screenshot of memo from Graham Williams to Head of Department. “Doctor Who – The Collection. Season 15 – Production Documentation” BBC Studios. Blu-ray.

Fig 13. Roberts, P., (1977) Doctor Who – The Sun Makers [online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00vfdsb/doctor-who-19631996-season-15-the-sun-makers-part-1 [Accessed on 08/06/2025]

Fig 14. Clarke, A., (1981). Psy-Warriors [online] Available at https://web.archive.org/web/20240713175902/https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/spaces-of-television/2014/02/24/the-stripped-down-studio-space-play-for-today-psy-warriors-bbc-12581-centre-play-the-saliva-milkshake-bbc-6175/ [Accessed on 08/06/2025]

Fig 15. Stewart, N., (1978) Doctor Who – Underworld [online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00vfhbd/doctor-who-19631996-season-15-underworld-part-4 and Stradling, E., (2010) Into the Unknown: The Making of Underworld Available at “Doctor Who – The Collection. Season 15. BBC Studios. Blu-ray. [Accessed on 08/06/2025]