This essay is also available on the Watching Blake’s 7 blog, for those who prefer a different text/background colour scheme.

The Man in the White Suit.

The story will be familiar to many. The ‘Acton Hilton’ rehearsal rooms, 1977. George Spenton-Foster, the director of the Doctor Who serial, ‘Image of the Fendahl’, decides to take the company for a liquid lunch. For the purposes of storytelling, let’s assume it is ‘The Castle’.

Chris Boucher, in that halfway house between Doctor Who and Blake’s 7, meets them on their return. It’s the first time he will attend a readthrough. With inhibitions down the drain, some of the cast, notably one ‘all tooth and curls’, start to dismantle Boucher’s final Doctor Who script. The ever aware Louise Jameson, tries to support Boucher’s acute embarrassment, to no avail.

“I went back to my office afterwards, and I just kicked the crap out of my filing cabinet. It’s probably sitting in someone’s office even now, with a bottom drawer that’s still unopenable because I kicked it so hard. I remember bringing down all sorts of curses on Tom Baker’s head, not the least of which that I hoped he would die horribly in a cellar full of rats.”– Chris Boucher 1

While Tom Baker was the focus of Boucher’s ire, I’m sure the director wasn’t exactly flavour of the month either. So, one wonders how the scriptwriter must have felt when he saw the name George Spenton-Foster on the list of directors for Series B of Blake’s 7. Perhaps he returned to his office to add a few more dents to the filing cabinet? Or, maybe he was imagining a scene in a future Blake’s 7 episode, where a strong character ends up in a deserted room full of rats?

And, even if he was, I’m sure Boucher hadn’t anticipated that the scene would be directed by none other than George Spenton-Foster.

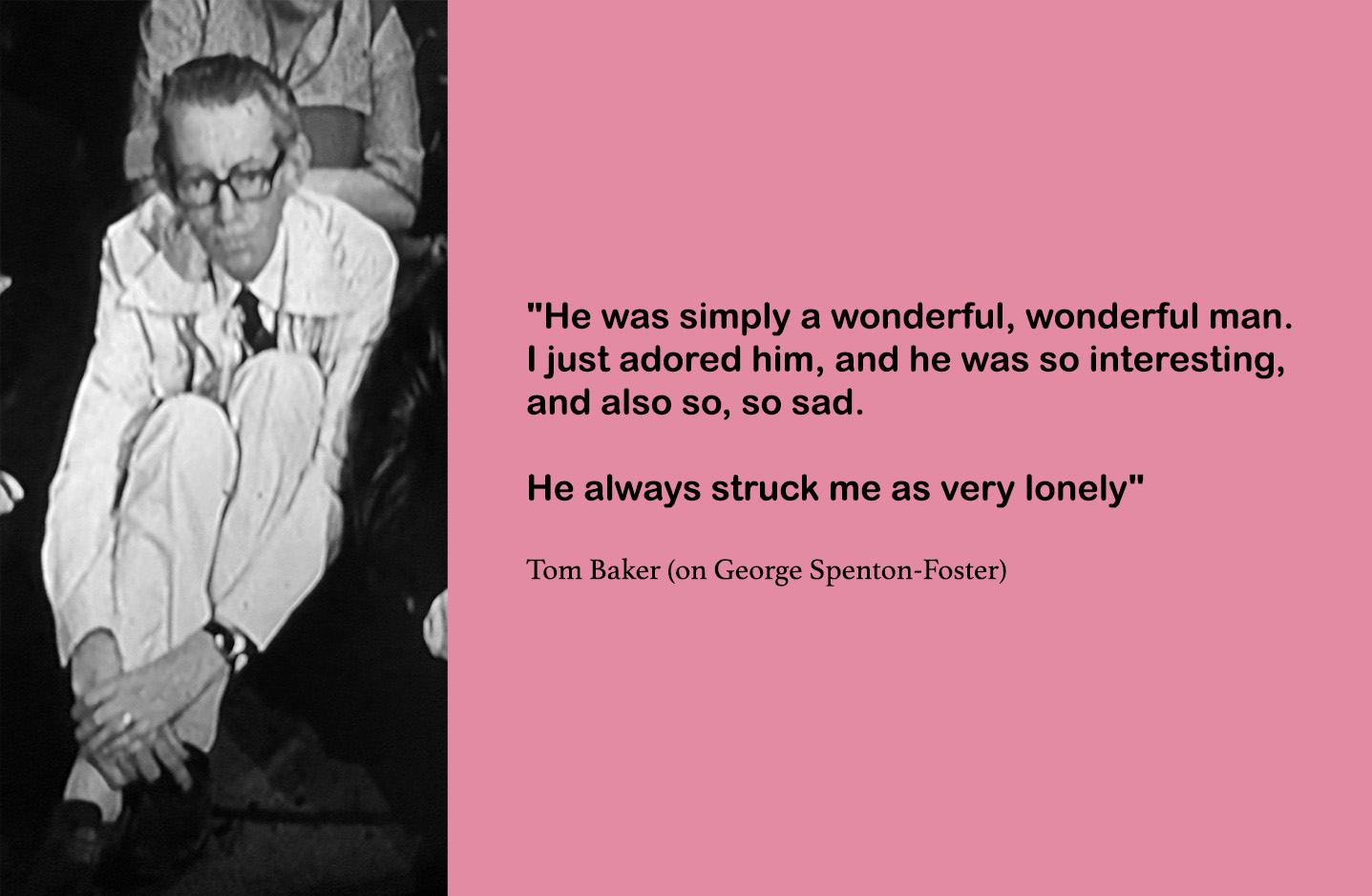

Little is known about Spenton-Foster, beyond the credits. For many decades, trying to find a picture of him defaulted back to the cast/crew photo for ‘Image of the Fendahl’, where it is possible to identify him sitting in the front row. Even then, it’s not easy to see him clearly, as that photo is usually blown up to such a proportion that his features look more like a Francis Bacon painting.

So, what can we glean about the man in the white suit?

There are smatterings of a biography. Thomas George Spenton was born in 1926. He was a cousin of the singer and actress Queenie Watts (Mary Spenton). 2 As George Spenton, he joined the BBC in 1948. The familiar progression followed – call boy, to production assistant, and then, by the early 1960s, he was producer/director. 3

What lore there is surrounding Spenton-Foster, tends to be painted with broad brush strokes, centred as much on his character as his professional work. “A lovely, camp old thing” (Tom Baker), “...camp as a row of tents, and very funny” (Paul Seed), “...a bit like a stick insect” (Wanda Ventham), an “old school” BBC staff director, (Judith Smith), “a very, very experienced director, and very thorough... He gave me a lot of help” (Mary Tamm), “He was a flatterer was George“, “Very popular with the cast and very helpful all the time. And much revered.” (Prentis Hancock.) Lots of affectionate recollections, then. On the flip side, there are also some accounts of actors being seen as puppets or a dislike of certain individuals.

4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

In terms of his career trajectory, there’s everything from an extended period as Associate Producer of Out of the Unknown, to a very short-lived cop series in Australia called The Link Men, which was axed after a 13-episode run. Just like others’ perceptions of him, his credits are a mass of contradictions, never settling.12

Delving a bit deeper, there’s a complexity to him. Tom Baker recalled “He was simply a wonderful, wonderful man. I just adored him, and he was so interesting, and also so, so sad…he always struck me as very lonely“. 13

Nigel Plaskitt (Unstoffe, in ‘The Ribos Operation’) notes how different Spenton-Foster was to other directors, in his openness to the actor being present for the editing and technical processes. 14

On the flipside, there are stories of tensions, both in the rehearsal room and on the studio floor. Jacqueline Pearce remembered the”chemical dislike” towards Brian Croucher and witnessed the “cruelty of the man” as Spenton-Foster apparently marginalised the actor on screen, initially reduced to a headshot on a monitor, and then, in a later episode, bandaged up. 15

John Nathan-Turner wasn’t well disposed to Spenton-Foster either, upon learning that both director and production assistant were giving the assistant floor manager (who was a friend of JN-T) a difficult time. It transpired that the PA was terrified of collaborating with Tom Baker, and the AFM ended up working with Baker very well, therefore not endearing herself towards the director or his assistant. 15b

Alcohol appeared to be a frequent companion. Although this was hardly unique to Spenton-Foster alone. He once told June Hudson that he always had a bottle of whiskey in the house, adding, “I don’t want to drink it, I just like to know it’s there.“16

“In those days, the BBC drama department – and this was a historical thing really, because by all accounts radio drama throughout the ’50s was very much the same – was kind of alcohol driven. Certainly, you hear the stories of when Dylan Thomas was working on radio plays. You know, other illustrious creators and wonderful characters there, who were half-cut most of the time. You’d be horrified now if you saw people doing half the things they did then. People like George were of that generation which everything kind of revolved around when the BBC club opened” – Paul Seed 17

There’s a fascinating, and somewhat sad, account of his involvement in the development of the Channel 4 soap opera Brookside – a senior figure who could ‘shepherd’ the inexperienced production team. Phil Redmond recounts how the production schedule started to unravel with tales of the director falling asleep on set, crew refusing to work with him, and a low turnover of footage. Whatever the truth, it is certain that Spenton-Foster and Brookside parted company, with early episodes not including a director’s credit. Spenton-Foster took his side of the story to the tabloids, with Redmond framing the resulting article in his office. 18

Taking Brookside out of the equation, the historical anecdotes suggest a strong-minded person who had a firm conviction of how things should be. This is amplified by an anecdote from Ian McCulloch, who played Greg Preston in the original version of Survivors (BBC, 1975-77), and who, by the time of the third series, had turned to writing.

“A Little Learning’, I count as a disaster, and I lay the blame wholly at the feet of the director. Apart from asking me who I wanted as the old lady, he didn’t ask me a single question during the rehearsal or filming. He cut and changed dialogue without asking me to explain anything, even though I was in the same room and he kept giving away the surprises.

For example, the audience are not supposed to know it is an episode involving children. As the camera approaches the house you see a big sign saying ‘school’. And when we hear screams from upstairs, you are supposed to think that someone is being tortured, but as the camera gets near, you see a sign saying something like ‘sick-bay’.

I had enjoyed writing it as it was meant to be an episode for Lucy, but when Terry Dudley [Producer] appeared on location while we were shooting ‘The Last Laugh’ he took me to one side and said ‘He’s f****d it up.” – Ian McCulloch 19

Another example of Spenton-Foster’s firm convictions is the ‘war of attrition’ played out during the production of ‘Weapon’ where he apparently refused to bow down to the threat of strikes, demarkation, union rules, etc, and brought in the episode at a reduced time. 20

For me, the more notable example is Gan’s death in ‘Pressure Point’. While the hurried production resulted in uncertainty about how Gan got trapped under the door, the more ignominious moment is David Jackson’s final ever Blake’s 7 camera shot. As the camera moves in, the beam and the debris are pin-sharp, but Gan is out of focus. No time for a retake.

So, there’s a complexity to the director, but what is far more certain to me, after a long time watching Blake’s 7 and Doctor Who, is an ability to bring out the drama through the handling of performance and an emphasis on the face.

Let’s take a good look at his work – close up.

A two-shot and a big close-up.

There is much that can be gleaned from Spenton-Foster’s telefantasy credits.

He produced the first two series of Out of the Unknown, and his occasional contribution as a director shows an ability to embrace the unconventional when depicting mental stress in ‘Lambda 1’ (BBC, 1966). This episode has a mixed critical reception, but I would say the fault is largely beyond the direction and more about the ability to tell a story within this particular 50-minute format. It’s telling that it had been held over from series 1, due to more time being needed to resolve various technical challenges.

Two things stand out from his work on Out of the Unknown. Firstly, Spenton-Foster is not afraid to try out some new approaches, presumably in partnership with effects designer Jack Kine. The twilight desert and all the hallucinatory scenes that make up ‘Lambda 1’ use multiple methods, from rostrum camera animation to reversed film, and liberal use of slow transitions.

Secondly, there’s his use of close-up. There’s a key scene in ‘The Counterfeit Man’, where Westcott realises he isn’t believed. Spenton-Foster goes in big for dramatic intensity. In addition, the framing of Westcott and Crawford is in profile, creating less of a sense of confrontation but more of a separation at this crucial moment between the two characters.

It’s the use of close-up that is the signature of ‘The Counterfeit Man’. It suggests that Spenton-Foster’s natural home was within the sensibilities of naturalism, emphasising dialogue rather than action.

Another series of note, Paul Temple, is where we really start to see his penchant for tasty close-ups. Naturally, I’ve selected some familiar faces that will appear in later Doctor Who and Blake’s 7 episodes.

Also, his two-shots are nicely composed. There’s always a deeper story being conveyed through facial expression, positioning and depth of focus. They’re far more than just being a couple of nicely framed faces.

There’s a special mention for the 1971 episode ‘Cue Murder’ where Paul Temple ends up on a live TV show.

It’s one of those fascinating snapshots of the BBC studio, unique in its mix of fictional and vérité – both up in the production gallery, and down on the studio floor.

Yes, I have watched it through in the hope of a Hitchcockian cameo, but there’s no insurmountable proof of whether he features in disguise.

His first contribution to Doctor Who, ‘Image of the Fendahl’ (1977), might be the ultimate expression of Spenton-Foster’s sensibilities. Again, he frames his shots in a way that emphasises the expression of the actors. This might sound like a common approach to any director, but it’s like there’s an industry standard close-up, and a ‘Spenton-Foster’ close-up. He exceeds it by zooming in an additional 5% of the frame, and 5% more than other directors. Of course, this is figuratively speaking.

As Edward Arthur (Colby) recalled, “...he liked his close-ups“. 21

This serial contains a slew of close-up shots that direct the audience’s gaze towards the eyes. On screen, the Doctor tells Leela and Colby not to look at Thea’s eyes, yet Spenton-Foster has us looking at nothing other than them.

The very first shot is a big close-up (BCU) of the skull, and it sets the template for the rest of the serial – tight, claustrophobic, and moody. Bar a field full of cows, and the faint sound of church bells, there’s no sense of expanse inside or outside Fetch Priory and its environs, and there doesn’t need to be.

I’d like to say that Spenton-Foster is most at home with the big close-up. However, as mentioned before, there is something about his use of the two-shot that ensures we not only focus on the eyes of whoever is talking, but are also conscious of what the interactions mean for the other character in the shot. When Dr Fendelman holds up the X-ray in wonderment, we look for clues in Colby’s expression – a hidden malevolence, or questioning? Also, when Moss makes reference to “the old ways”, we study Stael’s face in the foreground for clues about what it all means.

The framing between two characters can switch the tension, such as the concern registered by the character in the foreground, and ambivalence in the background.

The two-shot can also be used for different, lighter moments of drama. In one scene, set in Tyler’s cottage, Leela stares blankly into the middle distance, which makes her put-down of Moss ever more unexpected, and therefore extra delicious. And, one of my favourite moments is when we register the delight and dismay in the faces of our time-travellers when it is revealed that Earth is their next destination.

There are moments where Spenton-Foster tinkers with different types of two-shot. These suggest much about the characters. For example, Stael might be Fendelman’s closest and most trusted colleague, yet the shot below suggests a chasm between them that will be exploited later. Even the Wheelback chair (yes, I know, another chair reference) gets a lovely close-up, which importantly sidelines Thea Ransome to the margins. This feels apt, given the fate for the human aspect of her character.

The result of Spenton-Foster’s expressive use of two-shots, and simply going in that 5% closer when it matters, means that I am concentrating more on the motivations of the characters 5% more than I might be with many other directors I can think of. Even the ones who are untouchable in the orthodoxies of fandom.

Spenton-Foster’s second and final Doctor Who offering, ‘The Ribos Operation’, also contains its share of big close-ups, and is awash with effective two-shots. However, these are composed slightly differently, as the script is less psycho-drama and more about both the natural energy between characters and how they interact with the environment they exist within.

Take the two double acts: Unstoffe and Garron, the Graff Vynda-K, and Sholakh. They’re both inextricably linked to each other, and their dialogue is often conversational. Therefore, Spenton-Foster has each duo facing the camera, making us very much privy to their conversations. This is how we, the audience, listen in and are implicated in the ‘operation’ as it unfolds. Even Garron’s “Oh, Unstoffe, is there nobody you can trust these days?” is pretty much directed to the audience – as if we are guilty of eavesdropping. It is this formula that makes ‘The Ribos Operation’ one of my favourite Tom Baker stories.

However, the big close-ups are wheeled out when needed, and again, these are directed in a way that ensures we pay maximum attention to the characters. Take the conversation between Unstoffe and Binro, which is conducted in semi-darkness, with only the faces illuminated. The scene is framed and cut in such a disciplined way that we listen intently, alongside Unstoffe, rather than facing him. The camera starts to move in, as Binro reveals his speculation about the ice crystals being stars. When the time comes for Unstoffe to ratify Binro’s theory, that’s when Spenton-Foster goes in really big. It’s what frames Binro’s subsequent delight, and our sharing of his moment of realisation.

Spenton-Foster is also happy to break the fourth wall (or as near as damnit). These instances are usually reserved for the moments of great revelation, such as pronouncements like “No one messes with the Graff Vynda-K”, or “I invented that death. It’s called IMIPAK”, or “Then you’re going to be disappointed”. Tom Baker famously liked to address the camera and was clearly playing to a sympathetic audience in Spenton-Foster.

The other signature of Spenton-Foster’s work is his handling of pace. Again, ‘Image of the Fendahl’ feels like the ultimate expression of this. Cross-fades mix back and forth when the skull makes an appearance, and some scenes are unashamedly long. We will return to the theme of pacing later on.

At this point, I’m wondering – given this is towards the end of Spenton-Foster’s directorial career at the BBC – if we’re seeing a formula that clearly works for the small-screen, free of the types of innovation, or visual dynamism that fandom often likes to highlight; the sort that is usually singled out for your Greame Harper, Douglas Camfield, David Maloney or Paul Joyce. Then, I remember some moments of flair, evident in his two Doctor Who stories. The aforementioned slow mixing of the skull and Thea’s face in ‘Image of the Fendahl’ is one of the great late-1970s images, and the decision to record the catacombs of ‘The Ribos Operation’ with a soft glow adds much to the world envisaged in Robert Holmes’ script.

So, there is flair, but there is also flamboyance – another word often levelled towards Spenton-Foster. However, I would argue that this isn’t the dominant signature in his Doctor Who work. Sure, he sails close to the wind. For example, the “How dare you touch me” slap-on-the-face scene in ‘The Ribos Operation’ revels in its own outrageousness, not to mention the depiction of the Seeker, as portrayed by Anne Tirard, which is very out there – as it should be!

Yet, there is a line between what might be read as flamboyant (which I see as loud, confident, and bold) vs theatrical (which I see as more generalised, and with an ability to convey a range of themes and emotions). When you look at the rest of the performances and the costumes, they are definitely ‘on display’, but they sit comfortably within the world of the stage. It feels within acceptable parameters for the time, and it is the theatre that I see as the signature within his work, even more than any ‘far out’ results that can be seen whenever he got together with costume designer June Hudson.

“We all had enormous, wonderful, 360-degree cloaks. The whole thing, and I think you get this from watching, is very theatrical, which reflects George Spenton-Foster as a director, I think. His care about costume and the look of it is just terrific.”- Prentis Hancock. 22

There is perhaps the most ‘theatrical’ scene (as in a sense of stagecraft) in the history of all Doctor Who, as the Graff Vinda-K, with accompanying sounds of the big battle clearly audible, marches off to his death. I can’t think of any other director who would have the nous to make that scene work within the overall context of the serial.

Of course, this is a Robert Holmes script, but ‘The Ribos Operation’ feels positively neutered when you compare it to the next time Hudson and Spenton-Foster collaborate on Blake’s 7.

This seems like a perfect opportunity to analyse some of Spenton-Foster’s final credited directorial contributions to BBC television.

George Spenton-Foster and Blake’s 7

On paper, Spenton-Foster was a logical choice for Blake’s 7. He was fresh from Doctor Who and had a proven sci-fi track record, due to his involvement with the BBC2 anthology series Out of the Unknown.

I feel I’ve been a little unkind toward Spenton-Foster in previous iterations of the Watching Blake’s 7 blog, because I was never sure what he brought to the series. The four episodes he directed were, on the surface, so different from each other.

Take ‘Pressure Point’ and ‘Gambit’. Tonally speaking, there’s a chasm between both of them, straddling the ground between uncluttered, moody atmosphere and high opera.

If you take the costumes out of the equation, ‘Weapon’, and especially ‘Pressure Point’ are very economically directed, with some shades of flamboyance, but only a few moments of flourish. While this might also be due to the simplistic, and very white set design by Mike Porter (this is not a criticism), there is little in the performances, editing or sequencing that suggests a crossing of the line into overtly theatrical.

Then compare this to ‘Gambit’…

Some bemoan his direction on some episodes, with ‘Weapon’ criticised by its scriptwriter, ‘Gambit’ being criticised by its producer, and ‘Voice from the Past’ tending to be criticised by just about everyone. (Although I absolutely love it.)

Whatever the historical assessment, there’s always something new or contradictory to be gleaned from a rewatch, and it opens up new lines of enquiry. Perhaps, his strength is the ability to be adaptable in the style of different episodes? Given there’s flamboyance in many a Blake’s 7 episode, is it unfair to suggest this is Spenton-Foster’s calling card? Or, is his great skill how he handles important moments of spoken drama – specifically, pace, timing, and knowing how to make the big close-up really count?

Let’s dive deeper.

Case study #1 – the blocking between Servalan and Coser in ‘Weapon’.

Firstly, it is interesting to consider how Servalan was depicted in Series A. It’s clear that she can use her sexuality as a weapon, but it is more implied. Her softly spoken “Rai…Rai” in ‘Seek-Locate-Destroy’ lends weight to the “I thought we were old friends” line. At that point, it doesn’t matter as much – we barely know her.

At the drop of a fur coat, we reach ‘Deliverance’ where, apart from a hint of a touch when they share a drink together, Travis is expertly toyed with on a psychological level, to soften the blow of Maryatt’s death, and to ensure a degree of complicity in her secret plan to capture Orac.

After the Orac affair, the next time we see Servalan is in ‘Weapon’, and the first thing to notice is how her physicality and powers of seduction have been amplified. She is grabbed by the throat by a volatile Travis, only to caress his torso in a later scene. While the throat-grabbing is referenced in the script, the seductive non-verbal cue is not – beyond a beat. It adds a new dynamic between Servalan and Travis, where sex, violence and death are connected. It’s the first sign that we have a director who is comfortable with the gesture (presumably suggested by Jacqueline Pearce) and going a bit further with it than Series A.

The most interesting element of ‘Weapon’ is the scenes in Servalan’s office on Space Command. Things have changed since Series A. The ‘musak’ is still there, but we now have mood lighting. In the rehearsal script, Servalan simply presses a button on her screen, and then Carnell appears. By the time of the transmission script, the scene has evolved. There is a stage direction which includes the dimmed lighting. It’s a nice directorial touch, as it sets up the psychological mind games that are about to follow.

And then the dance begins…

It starts with a move from Servalan, as she faces away from Carnell – a calculated insult, and one that he deliberately ignores. Some of the best dances tell the story between two disparate characters, and this one begins perfectly.

The choreography is everything, and this is where Boucher’s script is transformed. Carnell invites himself to sit down in the chair, and after a bit of verbal back-and-forth, Servalan gets up, circles behind him and goes in for a seductive caress. If Spenton-Foster understands the power of a big close-up, he also understands what isn’t in the shot. We might be imagining where her hand is travelling towards, but as is often the case with his direction, we are laser-focused on his eyes and his expression.

The fact that she is behind him is important. For the first time, Servalan is depicted as totally dominant and truly dangerous. She doesn’t need to be confrontational to display this. I would say that Spenton-Foster is responsible for how we view Servalan throughout the remainder of Blake’s 7.

In the second scene between the two characters, there are other touches, like Carnell making himself comfortable by removing his outer garments when talking to Servalan. It’s perfect for his character, but it also adds another layer of sexual tension between the two. This stage direction is not present in the script, so the assumption is that this was worked out in the studio and approved by Spenton-Foster.

Reflecting on ‘Weapon’, Scott Fredericks (Carnell) described the director and his approach to the scene.

“[He was] slightly mad and he would go bananas on some things. I was given no instruction on how Carnell should be played, so I suggested to George that, being everyone else in the show was so gung-ho, and were rushing around the place being intense, it would be nice to play Carnell in a Noel Coward fashion – lightly, with a bit of humour, in a knowing sort of way. Bordering on the camp, but not quite camp, but then the costume was camp enough, so I didn’t have to do anything.” – Scott Fredericks 23

The final thing to note is the red floral decoration that Servalan plays with. It is exclusive to Spenton-Foster. In the DVD/Blu-ray commentary for ‘Gambit’, David Maloney returns to the question of famboyance, by describing a shot of Servalan sitting in a chair within her quarters on Freedom City as such a “George shot” 24. The decorative flower also makes an appearance in ‘Weapon’ and ‘Voice from the Past’. It is a small touch, but it suggests much about Spenton-Foster’s approach.

The pace of these scenes is so disciplined and effective. Returning to Michael E. Briant’s ‘Deliverance’, there is careful blocking, and Servalan is confidently lounging around, and the dialogue is delivered in a fairly natural rhythm.

However, in ‘Weapon’, the pauses between words are paramount. There’s the pause as Carnell receives the report that saves his life, and the final silent realisation as he sits in the office. This end-of-sequence long shot is added to the camera script, following a recording break, so it was clearly important to Spenton-Foster to get it right. It really makes the scene.

Even the exchange between Servalan and Travis immediately before Carnell’s first arrival is full of long moments of stillness between each line. The script might make reference to Travis expressing a ‘Cold Smile’ or talking in a ‘Softly-wry’ voice. On the page, though, it only has so much impact, without too much sense of timing or pacing.

That’s all changed by the time of recording. The transmitted scene requires Travis to try to make sense of Servalan’s motivations – “Travis, have you no sense of proportion at all?” The rehearsal script has Travis replying, “Supreme Commander?” in a puzzled way. The final camera script replaces this with a more direct “What!?” On the studio floor, this is delivered like a bark. There are further awkward pauses as the Space Commander tries to rationalise Servalan’s strategy. As already noted earlier, Spenton-Foster appears to understand the pace of a scene and the distance between lines of dialogue.

Of course, the most famous lines in the whole episode are found when Carnell signs off to Servalan – “You are undoubtedly the sexiest officer I have ever known.” While we might focus on Carnell’s eyelashes, the twinkle in his eyes, and his rationalising of what went wrong, the whole scene is all about Servalan, as the pivot shifts from anger to satisfaction – the climax of their brief dalliance.

This is an example of the embellishment that Spenton-Foster brings to the script; the smile is slightly more than ‘slight’, and the floral decoration becomes an important symbol.

However, Chris Boucher lamented the treatment of ‘Weapon’.

“I particularly disliked what happened on an episode of mine called ‘Weapon’. It had some cracking ideas in it. It also had a director who had his own ideas about bringing it in half the normal time. Unfortunately, you don’t get a little caption which says “this was made in half the normal time” because technicians, quite rightly, were working to rule at that time. And he was determined not to bow down. He was also not my favourite director.” – Chris Boucher 25

Production contexts aside, it’s hard to see how the chemistry between Servalan and Carnell could have been handled in any other way. When thinking about the distance between the script as written on the page, and how it can be read when realised on screen, it is interesting to think of the high risks involved in terms of authorship – often one sensibility will win out over another.

Overall, ‘Weapon’ marks the real moment where Series B takes form. The two previous episodes sit differently. ‘Redemption’ is in the mode of Series A, and ‘Shadow’, for all the nods to the political complexities that will distinguish this series from the one before, is so visually distinctive that it stands out on its own terms.

However, ‘Weapon’ is the beginning of an operatic style to Blake’s 7, such as the costumes, the choral music and lighting effects in Clonemaster Fen’s organic room. The distinct sexuality of the Carnell and Servalan scenes preempts another tonal shift – the sexuality that is inherent in Series C.

June Hudson’s take was that the director had seen it all before and wanted something new and outrageous. David Maloney wasn’t keen, considering that they “both fantasised to an incredible degree“. 26

This fantasy becomes ever more apparent by the time we reach the latter part of Series B.

Case study#2 – the discussion between Blake and Avon in ‘Pressure Point’.

This episode stands out as an example of the timing of Spenton-Foster’s big close-ups. The episode is full of them, and most of them surround Servalan, at precisely the right point. We go in big when there is relish at the prospect of capturing Kasabi, the affected expression as the freedom fighter regrets her inability to help her, and the rare moment of apprehension as she dials into the High Council.

On the Liberator, Terry Nation is going for the big-hitting statements during the first scene on the flight deck. “It’s a challenge”, “While it exists, it is invulnerable”, “I think I can destroy it.” Spenton-Foster channels Gareth Thomas’ energy and Paul Darrow’s ability to be dismissive. They’re both a little bit more animated than normal, particularly Thomas, who has muted his performance of Blake ever so slightly in the second series, giving off a character that is less charismatic and more absorbed in his own thoughts.

The slow hand clap from Avon drives us towards the conclusion of the scene (a long one at just short of three minutes). We finish with an explanation from Blake about how he has enlisted support from Kasabi and her not-so-merry group.

Blake’s line about not being alone – “I’d rather not try” is delivered sharp, abrupt, direct. It’s the point where Spenton-Foster goes in for a big close-up, taking us right into the mind of the lead character and his singular obsession. The timing is impeccable.

However, the most interesting scene in ‘Pressure Point’ is the celebrated moment between Blake and Avon, as they talk about the future. The scene starts off with another distinct pause, as Blake sits down, and eventually says, “The others have decided to go with me.” The pause is important, as it instructs the audience about how they should read the scene as it unfolds – part standoff, part negotiation. The pause is not in the script, so again, it’s something worked out between the actors and the director before the recording.

The second pause is after Blake asks Avon, “Do you want to tell me why?” In the script, there is a ‘hint of admiration’ from Avon towards Blake. On screen, this becomes another pause. Another ‘who will blink first’ moment.

The scene has been shot using medium close-ups (MCU) up until the point where Avon explains his rationale and longer-term goal to gain control of the Liberator. From the moment Avon reveals his hand – “With you running the campaign on Earth, someone has to take charge of all this” – we go in for a deeper close-up of Avon’s face.

We’re in a front row seat, and we’re all ears.

From this point onwards, every facial expression, every word is crucial to the power struggle – Blake’s amusement is met by Avon’s impassivity, Blake’s assured management of expectations is met by Avon’s direct stare.

And, this is where the third pause sits, following Blake’s reply, “There’s no hurry”. It acts as a conclusion to the conversation. The long stare towards Avon, and a moment of stillness before Zen announces an orbit around Earth, is essential to the scene. It’s the first real suggestion – within earshot of Blake – of how the future will play out. In this respect, another seed of Series C is sown here.

This scene reads beautifully on the page, and Chris Boucher’s dialogue is cracking. However, it is the directorial decisions that elevate it. As an aside, there is an acknowledgement of a pause in the script – the gap between Blake asking “And?” and the subsequent “Come on Avon, stop playing games.” However, this is a logical gap between lines. The other pauses are distinct ‘beats’ and enhance the drama. The timing of the close-ups and the distance between lines are essential.

‘Pressure Point’ is not the only example of how the use of pauses develops a scene. The Blu-ray information text for Boucher’s ‘Image of the Fendahl’ makes note of the timed read-through of a 25-minute episode at the beginning of the rehearsal process. By the time the actors are developing certain scenes later on, they are stretching the scene with the actors “playing the pauses” to their full value. 27

Again, it’s interesting that Spenton-Foster wasn’t Boucher’s favourite director, as the director’s approach to pacing emphasises every scripted line and its intent.

Case study#3 – Servalan’s victory over Le Grand in ‘Voice from the Past’.

Apparently, George Spenton-Foster was selected to direct ‘Image of the Fendahl’ due to his expertise in night filming, notably on Z-Cars. 28 This feels slightly ironic given that there were problems with generators, a significant overrun, and an official BBC apology for the disturbance to a member of the public. While this example illustrates the complexities of a night shoot, there is no evidence to blame Spenton-Foster. In fact, the proof of his expertise is all there to see on the screen. The shots are dynamic, in particular the tracking shot of the hiker. Also, the composition is atmospheric, and the lighting is exceptional, working in sync with the use of dry ice. In short, Spenton-Foster makes full use of the location to create a memorable climax to episode 1.

This is worth keeping in mind when analysing a scene in his third Blake’s 7 episode, ‘Voice from the Past’.

This is a story that has a pretty poor reputation. While many bemoan the hurried C.S.O. shots of Blake walking across the barren landscape of Asteroid P-K118, and there are questions arising from the change in actor portraying Ven Glynd, a lot of it is centred on the portrayal of Travis/Shivan, and that accent.

I’m going to stick my neck out and say that – Travis aside – it’s not that badly directed. There was a choice to be made, given the dourness of the script – either go for full realism, which Blake’s 7 demonstrated it could do in ‘The Way Back’, or ask the question of what the show has evolved into.

For me, the answer was a balance between psychological drama and operatic flamboyance. And it worked. Even the viewing figures were good for Series B, given that it was shown in Wales at an uncivilised time.

So, Spenton-Foster shifts from the relatively conventional ‘Pressure Point’ towards something more operatic. And, it is right for ‘Voice from the Past’. The performances are big and egoistic, which totally makes sense for the characters involved – you can’t be reserved if you’re plotting a coup against a dictatorship. Frieda Knorr plays Le Grand perfectly, and is offset by a more measured portrayal of Ven Glynd. Servalan’s office scene, where she spars with Le Grand, is just wonderful.

I’d like to think I’m slightly, but not completely tone-deaf to the criticisms levelled towards the direction of this episode. The regular cast are perhaps too comfortable in their portrayals. It comes across on screen, from the moment where Avon is making sense of Blake’s initial psychological attack, to Jenna’s assessment of the surface of the asteroid. And, of course, Brian Croucher is served very badly by this episode.

Yet, it remains a guilty pleasure, and given how Blake’s 7 continues to evolve in Series C, I think it was right to go for a more ‘fullsome’ direction.

However, there is a scene that is not only the stand-out moment in ‘Voice from the Past’, but also one of the great Blake’s 7 sequences of all time – where Servalan has her sport with Le Grand at the Atlay conference hall.

Firstly, a glance at the rehearsal script reveals the basic scenario, with Le Grand and Ven Glynd walking through a set of double doors into an empty arena. There’s a reference to the P.O.V from the perspective of both characters, and an additional line where Servalan invites them into the space.

By the time of the camera script, things are starting to develop, with reaction shots of Le Grand and Glynd, interspersed with cutaways to the main hall. These react to Servalan, who is projected on a giant screen, rather than using C.S.O., which could not be achieved on location film.

However, it’s Spenton-Foster’s ability to bring out the full potential of the location, and a few other touches, that result in this scene becoming a classic.

We start with something fairly orthodox – two establishing shots of the arena.

Things start to ramp up as the lights fall. Once again, it’s all about the pace. The lights don’t simply switch off in one go, as in an interrogation. The cascade of lights mounted on the walls is turned off one by one, like dominoes. Just imagine how this scene would play out if the lights just fell in one go? One suspects that Spenton-Foster asked a question to those responsible for the Wembley Conference Hall – can the lights be switched off individually?

The answer was yes, and when this is combined with slow, suspenseful notes from Dudley Simpson, there is a sense of assurance – the impression that Servalan has created a trap that can’t fail. She has them where she wants them, and doesn’t have to pull the trigger … just yet.

The next shots remind me of why Spenton-Foster was seen as an expert in night shooting. The spotlight on the condemned – the back light on Le Grand is simple and effective, conveying the trap the characters have walked into.

The slow fading of the lights in the arena paves the way for Servalan to suddenly appear, unannounced. This is where the P.O.V stage direction comes into play. The framing of this shot, and Servalan’s slow, satisfied look up toward Le Grand, is delicious.

Then, in true Spenton-Foster tradition, we see two shots – both big close-ups (BCU) but very different to each other. The first BCU is of Servalan’s eyes. It might be a cliché, but clichés often are what they are, because they are proven to be effective time and time again. Servalan has psychologically ensnared them both, and her eyes are the expression of this.

The second BCU is the reaction shot of Le Grand. Going in for that proverbial extra 5% means we see the defeat etched into Le Grand’s expression, as she stares directly into the eyes of her victorious opponent. We return to the naturalistic elements of Spenton-Foster’s approach to directing – the eyes, the expression, the mouth that wants to say something, but there are no words left.

It would be easy to stop there. But Spenton-Foster – the director who can go that extra mile in terms of flamboyance – elects to shoot two additional shots that he drops in at various points. The eye and the mouth emphasise Servalan’s effortless control of the situation – the assured psychological victory.

There are further flourishes. Servalan glances to the left of the screen, and the skeletal outline of two Federation troupers appears, with an intimidating slide light.

And, same again to the right…

One presumes that Spenton-Foster was thinking about the opportunities afforded by the conference hall during a recce, and then tailored his filming of Servalan to include the additional shots that best utilise the vast space available to him.

As per the script, the volley of shots rings out. Spenton-Foster directs Knorr to make her death operatic, rather than silent. It works for me. The scene has been dreamlike, but with the flash of the Federation blaster, we’re slapped in the face with a dose of reality. We need to hear this most dignified of characters scream.

It’s all there. The pace is calculated. The lighting works for a scene set at night (even if, technically, the script says ‘day’). The utilisation of the location. The impact of a big close-up. The touch of flamboyance and flourish.

George Spenton-Foster, take a bow.

Case study#4 – ‘Gambit’.

‘Gambit’, for all its unique qualities, is oddly the least interesting to analyse. It’s hard to pick out specific scenes to break down, given the episode is tonally and technically undiluted Spenton-Foster.

Yet, for all its bombast, ‘Gambit’ can slip into a gritty, realistic tone. You just have to look for it under all the tinsel.

The opening scene just confronts us, without any kind of establishing shot or fanfare. It might feel like it’s come out of a Western, but it’s played relatively straight. Denis Carey plays Docholli with a mix of aggression and emotion. We learn lots about the characters, and the setting is decorative because that’s exactly what it is, rather than any attempt to be flamboyant. In fact, most of the scenes set in Chenie’s bar are largely free from any flourishes. The same is the case for the final scenes in the docking bay. There are even a few elements in ‘Gambit’ that are toned down from previous episodes. Travis, for instance, is played as low-key as he’s ever been before. Blake is as singular as ever. The orchestrated music is nonexistent, replaced by electronic atmospheres.

Less measured is the location work. It’s a creative mix, with coloured lighting suggesting an exciting time nearby, yet it contrasts with the howling wind and suggested harsh terrain of the planet. There are other touches, such as an interesting/odd/innovative (delete as applicable) shot of Travis’ shadow being clonked, and the resulting wandering camera.

Of course, ‘Gambit’ really comes alive, with the scenes set on the Big Wheel, and anything involving Krantor and Toise. The leading characters are an obvious example of the tone of this episode. However, David Maloney singled out John Leeson, who was cast as an aide to Krantor, yet is somebody who “out-camps, well, everyone.” 29

Even the awkward threesome between Servalan, Jarriere, and Travis is entertaining due to the colliding dynamics of all three characters. All the signature Spenton-Foster ingredients are present: the pace within the longer scenes of exposition, the movement and blocking of characters as they interact with each other, the use of carefully timed close-ups, and the emphasis on emotion and expression.

And, there are flourishes. The angled shot looking up towards the Croupier. The Regency theme. The gesticulations in the performances. Oh! The performances!

“David Maloney wasn’t very happy with ‘Gambit’ because George was outrageous and stirred things up, you know, he was a bit of an outsider, he wanted to do things that were different and daring, so I suspect that’s one of the reasons why he wasn’t invited back to direct for season three”. – Jacqueline Pearce. 30

Back to reality. There are moments where Docholli can’t get his coat on, or a shot of Jenna on film, taken from an earlier scene, and placed in a way that doesn’t make any sense. Both remind me of the anecdotes that surround the hurried production of ‘Weapon’. In these instances, retakes and additional cutaways are necessary. But then again, the world would be a lot duller place without the fur coat.

‘Gambit’ is a million different chess matches all squeezed into 50 minutes, some played with the eyes, some with booze, some private, and some with an audience. I think it’s Spenton-Foster’s final directing credit for the BBC. As such, this episode is the raucous farewell party.

And, it’s just as well. Fuck, can you imagine if George Spenton-Foster got his hands on ‘The Harvest of Kairos’?

In conclusion

Like his personal reputation, Spenton-Foster’s contributions to Blake’s 7 are a myrass of contrasts, moving from gritty or resolute, to operatic and flamboyant. He has a strong grasp of framing and visual language, and is not afraid to use music economically (‘Pressure Point’ and ‘Image of the Fendahl’ are very sparse.) At times, his style is at odds with the intensity of the episode, and other times, he is spot on. More broadly, he brings something new to the second run of episodes. With more flamboyance and flourish, he is an important part of Blake’s 7’s distinctiveness – the ability to be operatic. Therefore, he is the bridge between the gritty Series A and the melodrama of Series C.

All in all, if you compare the tone of his Blake’s 7 work to the tone of his two Doctor Who stories, there is a breadth of approaches that might be expected from an experienced director.

Perhaps, there is more to it than that? While all have various sensibilities, I’m often reminded of the type of anecdote where a director prefers to work on one type of story rather than the other. A good example is Paddy Russell’s insistence that she directs stories that are big on character and plot, and free from monsters and endless technologies.

Spenton-Foster is of the same era. He advanced to director at a similar time to Russell. Therefore, if the 1950s belonged to the school of Rudolph Cartier, the 1960s were the time when production assistants would start to blossom as producers and directors. Both Russell and Spenton-Foster made their final contributions to Doctor Who around the same time. From this point onwards, there is a sea-change on the show. There are occasional appearances from contemporaries of Russell and Spenton-Foster (Christopher Barry, Terrance Dudley, Peter Moffatt), but largely the directors are now those who came up the ranks in the latter 1960s and 70s, and had a different perspective on how television drama could tell stories. So, when the critical assessment states that a particular director avoided certain approaches to storytelling or technological processes, that might be the case. However, in the case of George Spenton-Foster, I think he just didn’t need to use those techniques in the first place.

This also suggests different approaches to innovation. Sometimes, a director who brings something fresh, new, and dynamic is measured by a comparison to film and cinema. In Doctor Who, Lovett Bickford and Paul Joyce all brought a new sensibility, drawn from the single-camera technique of film. Peter Grimwade’s direction of ‘Earthshock’ saw the cinematic approaches of framing, lighting, and pace being all for the benefit of the final edit. Greame Harper tested the limits of multi-camera technique, not just through the composition or shot selection, but in pushing the conventions of how one directs when in the electronic television studio.

I would argue that Spenton-Foster was an innovator, too. The difficulty here is that these innovations are not often seen as such, as they were not about moving from one paradigm to another (from multi-camera theatre to single-camera cinema). His innovations were about emphasising what already exists – the naturalism of multi-camera, the contexts of the theatre. This explains the ‘5%’ extra in a close-up, the extra textures on a costume, or the amplified performance.

With this in mind, I return to somewhere near the beginning of this article – the comment made by Tom Baker about George Spenton-Foster having a ‘lonely’ quality about him. I know little of his life, so I can only speculate on what this meant to his connections with people, or the output on screen. The loneliness, for me, is in how he sticks out in terms of how he is critically assessed. It’s more difficult to contextualise his work, given that he is one of the very few directors across Doctor Who, and certainly the only director in Blake’s 7 who has never (to my knowledge) given any account of his time behind the camera. For us telefantasy fans (yes, I still enjoy using that word), our reading of Spenton-Foster’s direction across the late 1970s is often focused on a short period of time, at the end of a long career, so our judgments do not take into account his career or personal approaches more broadly.

That he is regarded both affectionately and with disdain suggests a reputation that is unlikely to be truly understood, unless there is a ‘Looking For’ documentary on a future Blu-ray. (That isn’t a suggestion that there is one being made, by the way). The latter years, like much of his life, are vague. Reports say he died of alcoholism. 31 The actor Derek Martin mentioned how Spenton-Foster ran away to Australia with a BBC barman. 32

But, we can’t be sure. For a man who liked his close-ups, our understanding of George Spenton-Foster is, like the photo of him in the white suit, very far away.

Thank you for reading.

I always put a lot of effort into these ramblings, so if you enjoyed what you have read, do feel free to buy me a coffee.

Americano, no milk or sugar. I’m grateful if you do. 🙂 https://buymeacoffee.com/thetimdickinson

(1) In-Vision. Issue 26, August 1990, CMS.

(2) islandhistory.wordpress.com/2014/03/03/the-quest-for-queenie-the-voice-of-the-island/ – accessed 1/12/25

(3) (12) (31) http://www.shannonsullivan.com/drwho/bio/george-spenton-foster.html – accessed 1/12/25

(4) (16) Doctor Who Magazine – The Impeccible Tom Baker (with June Hudson) Issue 501 – July 2016.

(5) (14) (17) (22) The Ribos File. Dir: Ed Stradling. 2007. 2-entertain.

(6) (8) (9) (13) (21) DVD Audio commentary – Image of the Fendahl. 2009. 2-entertain.

(7) (10) (11) (20) (25) Liberation: Blake’s 7. Year 2. Dir: Chris Chapman. 2025. BBC Studios.

(15) Deliverance 1998 panel with Sally Knyvette and Jacqueline Pearce. Blake’s 7: The Collection – Series 2. 2025. BBC Studios

(15b) Richard Marson. The Life and Scandalous Times of John Nathan-Turner. Miwk. 2013.

(18) Phil Redmond. ‘Mid Term Report’. Random House, 2012.

(19) http://www.survivorstvseries.com/Ian_Interview.htm – accessed 30/11/25

(23) https://www.kaldorcity.com/people/sfinterview.html = accessed 30/11/25

(24) (29) Audio commentary – ‘Gambit’.. Blake’s 7: The Collection – Series 2. 2025. BBC Studios

(26) Jonathan Helm, (Designed by G. Robertson) 2024. Blake’s 7 Production Diary. Series B. CultEdge.

(27) Information Text for ‘Image of the Fendahl’ 2024. Doctor Who: The Collection – Season 15

(28) Doctor Who Magazine. Archive feature. Image of the Fendahl. Issue 193. Andrew Pixley. 1993.

(30) https://www.kaldorcity.com/people/B7jpinterview.html – accessed 30/11/25

(32) https://www.bigfinish.com/releases/v/toby-hadoke-s-who-s-round-115-the-stuntmen-1245 – Toby Hadoke’s Who’s Round. 2015. Big Finish.

And thanks to Tragical History Tour for the caps.

Leave a comment