A darkened room…

A cat howl…

and, the rising swirl of Mussorgsky’s ‘A Night on the Bare Mountain’…

It’s the early 1980s, and ‘behind the sofa’ doesn’t even begin to describe it.

The combination of sound and imagery, was the cue for my 5 year old self to run out of the room. This advert for Maxell, and the one that preceded it, were my first, long-lasting, televisual memories, and really opened my eyes to the power of the Sony Trinitron in the corner of the living room.

So, I really wouldn’t be typing here if it were not for these two masterpieces of the small screen.

But before we talk about Maxell, let’s cast a net over some other grown up television commercials that made an impression on me during my childhood, when I wasn’t hooked on anything toy-related that ended with the logo ‘Action GT’. I have a feeling that there are common themes to be discovered.

The 1980s – from comfort to confrontation.

I’m increasingly drawn to the conclusion that there was, in television advertising, a steer from the comfortable in the 1970s, towards the confrontational in the 1980s.

The adverts I remember most, often juxtaposed familiar imagery with a sometimes arresting tone.

Take this advert for Andrex – ‘Feathers’ (Dir: David Thorpe, for JWT/Scott, 1981.)

On the surface, this is a series of playful and soothing images involving the famous puppy. However, it is flipped completely on its head through the inclusion of the David Vorhaus composition ‘Sea of Tranquility‘ (Kpm 1000 Series, 1980.) The cascading electronic sounds create a serious, technological edge, and the pink space becomes an immersive, enclosed, and almost suffocating environment. This child remembers feeling mildly disorientated every time I saw it. Probably not what the advertisers were aiming for.

Clinical, synthesised, sombre. These are words that also describe Richard Myhill’s soundtrack for the ‘Thoughts’ campaign (Dir: Bernard Spencer, for Norman Craig And Kummel/Shulton, 1982.) This relaunched ‘Mandate Aftershave’ in the 1980s, moving away from the ‘likeable’ (featuring Sacha Distel’s own brand of crooner-appeal) towards a more ‘powerful’ representation of masculinity. On the surface, the premise is simple: man walks out of a shower in the background, and woman erotically caresses the ‘Mandate’ packaging in the foreground, while describing her attraction to him through a voiceover. Pucker up, he walks towards her…

(Note: this video is a very truncated version.)

Yet, the soundtrack is anything but seductive, and creates an entirely different feel from Distel’s more accessible brand. The minor key score and clinical arrangement nods more towards Ken Freeman’s theme tune for the BBC1’s Casualty, which premiered a few years later. Combined with a modern and charmless bathroom, the vibe is ‘status’ rather than decorative, with the setting suggesting more hospital than home. So, when the man in question bears down towards the camera, it becomes more threatening than fanciful, and the staccato jump cuts between him and the product (presumably, a technique borrowed from the famous ‘Old Spice’ commercial) create an intensity that was disarming when watching as a child.

Some people seem to remember the man looming towards our faces. Once again, I was sent running out of the living room. And frankly, who can blame me?

This more uncompromising approach mirrored the times. Suddenly, it was fashionable to break the fourth wall and directly confront the viewer, with sneers, glares, or moody glances, or occasionally smiles – as is the case of ‘blessed relief’ for the man who surfaces in the ‘Mu-Cron’ advert of the mid-1980s.

Or, the unique ‘two-in’one’ advert for 1985’s ‘Supersoft Set Two’ hairspray (Dir: Willie Patterson for Boase Massimi Pollitt) where we are ordered to buy it through direct instruction by Ian Holm, and a smidge of persuasion by the actress, whose name I can’t recall.

Based on the youtube comments, the effect seems to send people running out of the room.

The other mechanism is to portray the central character in a moody and atmospheric way – confronting the audience with a strong visual. A good example of this is the near-legendary campaign for ‘Quatro’ – the short lived (in the UK) soft drink of the 1980s. One of the common themes of this campaign, and the follow up a year or two later, is the inclusion of an atmospheric noir style gobo shot (also used in ‘Supersoft Set Two’) that portrays the tough cookie who features in the ‘Alien’-esque surroundings of whatever dystopian surroundings he is in.

The first campaign is of particular note. ‘The Machine’ (Dir: Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel, for Kirkwood & Partners/CC Soft Drinks) just screams 1980s, with a mix of moody live-action and computerised imagery. Considering the directors – who founded Cucumber Studios – were responsible for everything from Max Headroom, to the famed bursting-out-of-the-TV titles of Channel 4’s The Tube, it’s hardly a surprise.

The follow up ‘Special Delivery’ (1985) riffed on the same themes of man v machine. The styled waves of hair give way towards a more Bon Jovi-esque perm, with the character ‘starkicking’ (in The Old Grey Whistle Test tradition) a malfunctioning machine until he gains his precious can of fizz. At least when Zammo needed something in Grange Hill, he always said please.

In both campaigns, it was the person, rather than the product, that stood out in my young mind. And it reminded me of perhaps my ultimate, formative, television memory, that premiered a couple of years earlier.

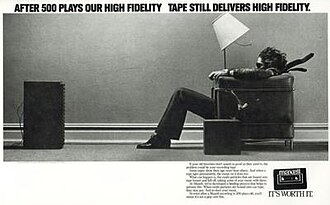

Maxell was a Japanese electronic company founded in the early 1960s. It was noted for it’s audio products, including cassette tapes. As the 1970s gave way to the 1980s, the company had a modest foothold in America. Previous adverts had targeted the audiophile. Scali, McCabe, Sloves, were the agency awarded the contract to broaden Maxell’s appeal. The result, in 1979 was a distinctive print ad, followed in 1980 by a TV spot. The image of man clinging onto a LC2 chair while the Maxell sound buffeted him became a celebrated image. Of course, ‘The Simpsons’ referenced it. (5)

The campaign – ‘Blown Away Guy’ travelled across the pond, and by 1982, Downton Advertising were awarded the contract to remake the campaign for UK audiences. And, the creative team made it something completely unique, and culturally removed from its American counterpart.

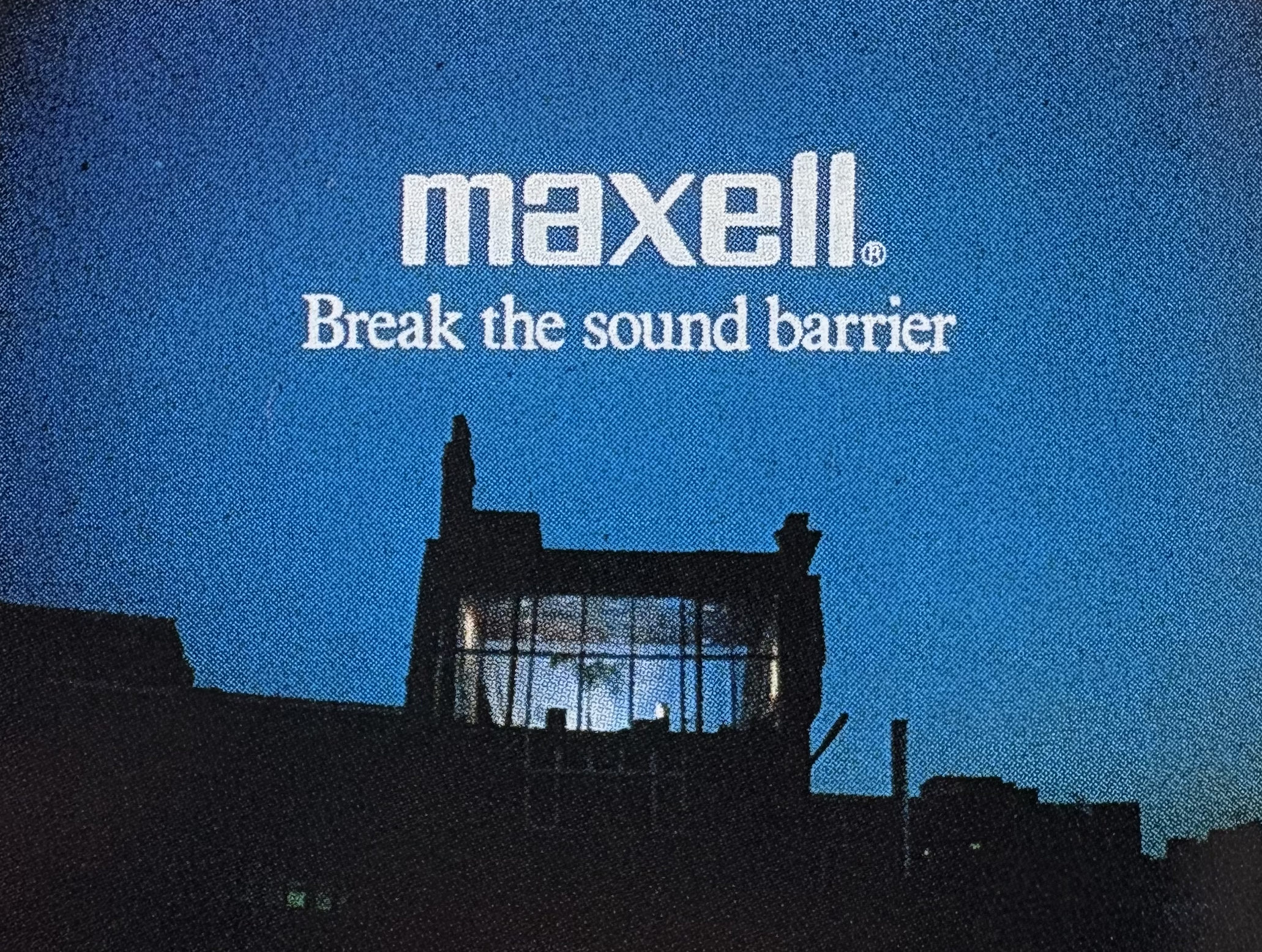

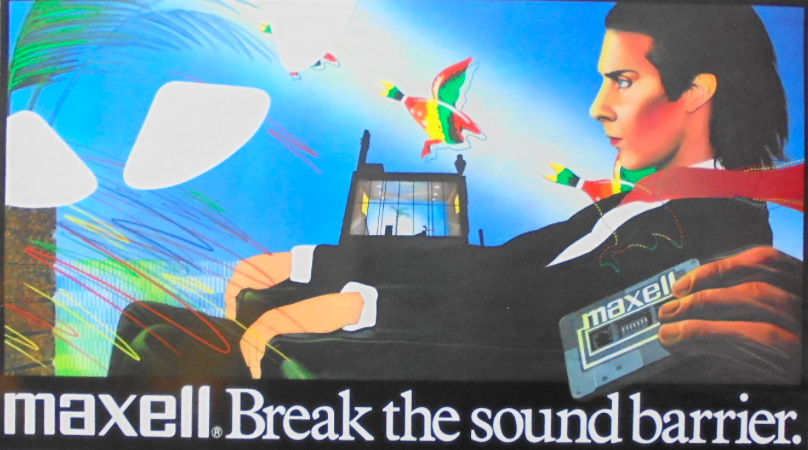

Advert 1 – ‘Break the Sound Barrier’.

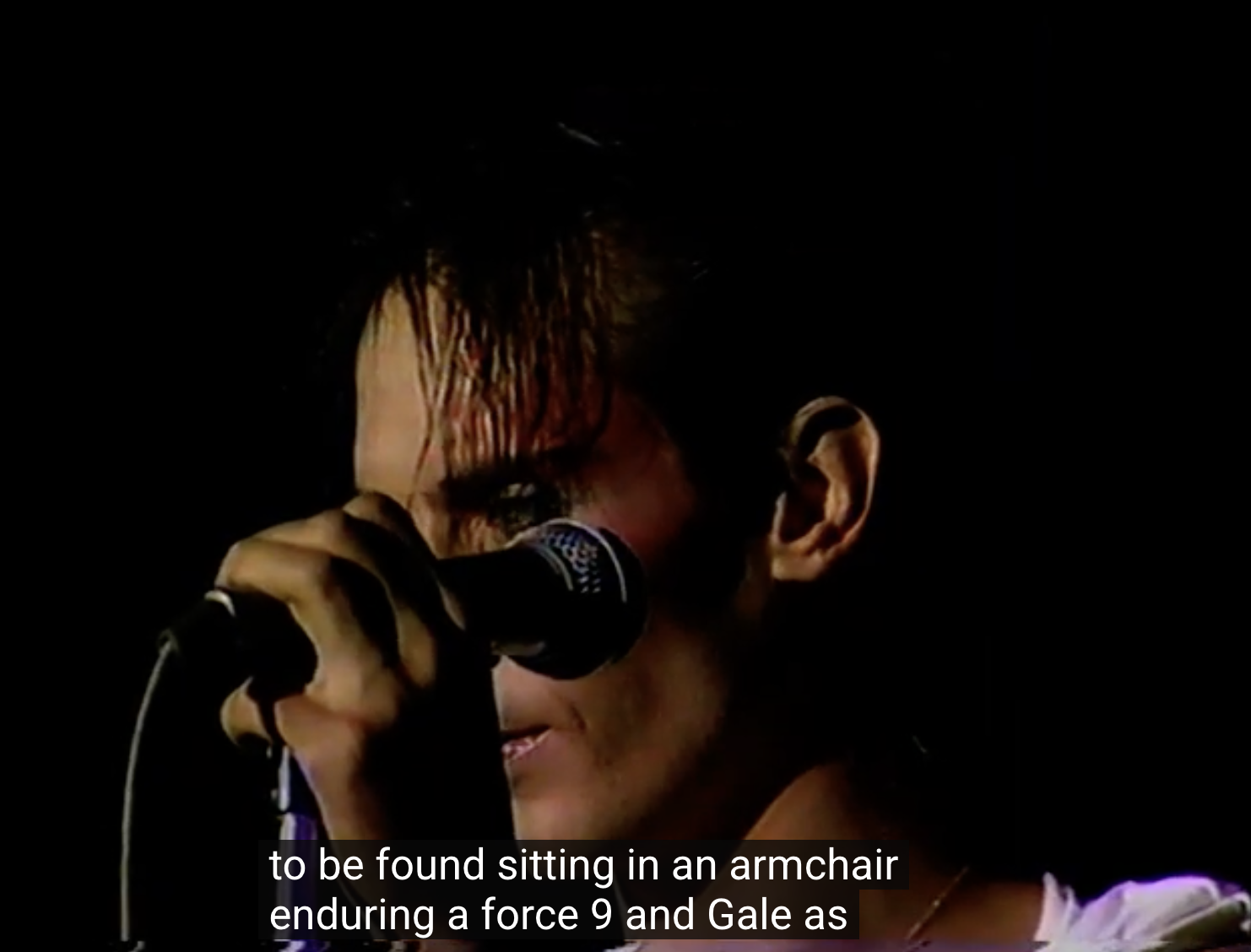

The first advert was called ‘Storm’ and produced by Downton Advertising. The setting is a living room. A man (played by Peter Murphy) places a cassette tape into a hi-fi, and the quality of the sound is expressed as a storm.

All hell breaks loose, and like the American campaign, the central character is left clutching his LC2 armchair.

Murphy shoots the audience a very unnerving glance – reinforcing the sense of confrontation that distinguished the 1980s from the decade before.

The advert ends with a exterior shot of a silhouetted house, with the storm raging on inside. The final tagline ‘Break the sound barrier‘ appears as both a caption, and a whispered voice (presumably Murphy himself.)

It’s easy to see why this Maxell advert is memorable to so many; the eerie, silhouetted house, arresting imagery, the infrequent electronic noises and cat howls that punctuate the sequence give this an unsettling edge. The choice of music – Mussorgsky’s ‘Night on the Bare Mountain’, already famous for its inclusion in Disney’s ‘Fantasia’, creates a suitably stormy feel. And let’s not forget Peter Murphy (yes, the lead singer of ‘Bauhaus’) as his steely glares towards the camera, alongside other impassive facial expressions, give added spook value.

The making of.

I sought to track down anyone who might be able to shed a bit more light on these terrifying memories. I was lucky enough to make contact with director Howard Guard, who has enjoyed a successful career on both sides of the Atlantic. He was kind enough to shed some light on the making of the advert.

Guard suggests that the Ride of the Valkyries scene in Apocalypse Now was an influence, but unlike that film, the advert was a low-budget commercial, resulting in all kinds of smart thinking to achieve the footage required.

The ducks were on wires pulled by a man hanging over the top of the set.

The low angle tracking shot onto Pete’s shoes was by putting the Arri on a sheet of hardboard (shiny side down) and me pulling it, and the focus puller running alongside. I had an industry phone call about it at the time asking where we got the rig.

The coffee vibrating was created by a small compressor next to it.

The lightning was open fronted Brutes and a man arcing the carbon” (3)

In basic terms this a technique for activating the huge lights you might see on a large-scale film shoot.

The visual ingredients needed to be strong. The coffee cup is postmodern, the patent shoes, sharp. Guard recalled that the footwear was sourced from Robot on the Kings Road.

They quickly sold out! (3)

The toy robot is a design classic – manufactured by Yonezawa, Japan, 1970-1975.

Although the actual ducks featured in the advert are hard to identify, the flying duck design originated from Stoke On Trent – no surprise there. The Beswick figurines were first produced in 1938, and became a popular – and affordable – interior artifact.

The audio set up is a Nakamichi 1000ZXL.

And the chair is a classic. The LC2 – Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Charlotte Perriand, 1928.

This is an advert that relies on the skill of filmic technique, rather than any kind of special effects work. At the time of transmission, Guard noted:

It was never intended to be a slick piece of optical trickery. It was simplicity itself; all in the shot material and the editing.” (2)

Ironically, for an advert that places such a strong emphasis on sound, sometimes it’s fun to turn the volume right down and think about the studio floor. The sheer effort and coordination that Guard mentioned. Marc Hill was the art director on the shoot:

Half the construction crew were behind the wall moving the ducks and various props with Howard shouting “more, more” like an old-time silent movie director.” (1).

It’s this image that I’m drawn to frequently, as I think of Guard directing the crew to make the magic happen; the music replaced with the sounds of shouting, orders and commands, industrial wind machines, crackles of lights being ignited, and assorted creaks and whooshes of various objects swaying in the storm of the living room.

Usually we only got a few days notice on these commercials so it was full on getting the set designed and built and anything not concerned with it was blanked out. Howard’s shoots were always full on as well – no peace for the wicked or general chat. (1)

But what we did hear in the end was a classic piece of music. Guard recollects that the advert was edited to two different sound tracks.

“I cut the film with Simon Laurie to Mussorgsky’s ‘Night on a Bare Mountain’ and a second version to Tchaikovsky’s ‘Romeo and Juliet.’ I loved both versions but we went with Mussorgsky in the end.” (3)

And it’s an inspired choice allowing the score to fade down naturally and let the very sinister whispering voice deliver the “Break the Sound Barrier” tagline at the end.

This accompanied a shot that many will have taken into the next advert. Gaurd recalled that it was filmed during the ‘magic hour’ – aka sunset.

The cameraman on the exterior shot was Hughie Johnson and was his first job.

Johnson had a number of credits before Maxell, but Guard’s recollection suggests this was his debut as first, rather than assistant, camera operator. He would later work with Ridley and Tony Scott.

Thanks to Guard, I was delighted to discover the location of the sinister house that features in silhouette at the end of the advert. This was the top floor of Yugin’s – a former mannequin studio in London, just off West Cromwell Road, and it still stands today. It was one of those moments where, after all this time, I’m still amazed at the power of the internet, allowing me to find an obscure house that featured in a television commercial from the early 1980’s – pure television archeology.

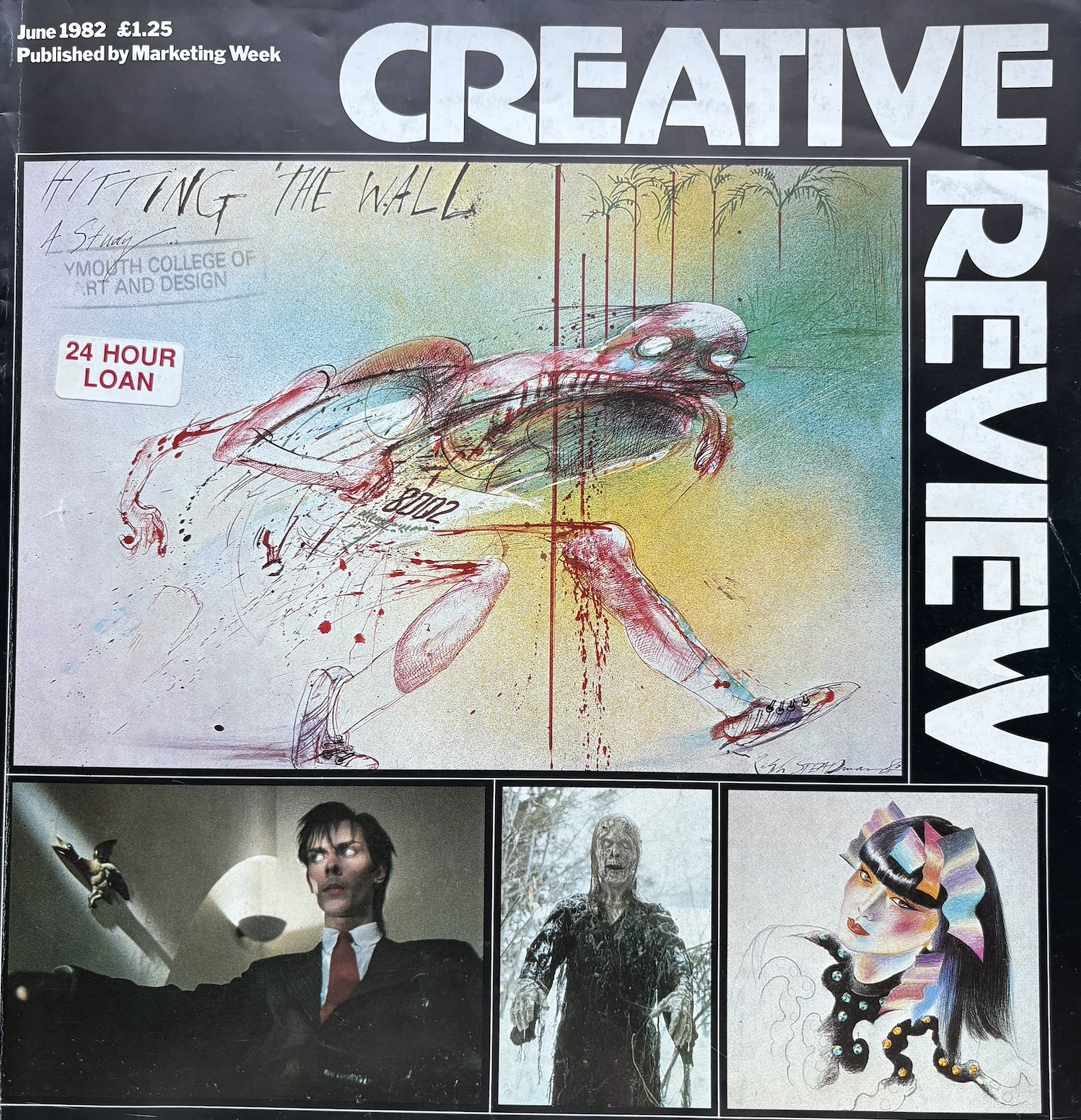

The advert immediately had an impact, as noted by the Creative Review article ‘The Sound and the Fury’ (June, 1982)

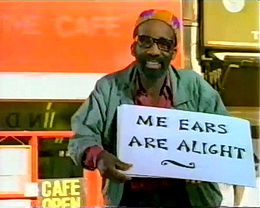

“From the time of the first transmission, Downtons received sacks full of mail and numerous phone calls about the commercial. Many were simply congratulatory; others demanded to know where they could buy the man’s shoes or even where they could find the man. And Peter Murphy of Bauhaus, the man in question, has found his subsequent TV appearences and concerts interspersed with references to Maxell, thrown in by the audience.” (2)

An oft-quoted rumour was that Japan’s David Sylvian was originally in the frame to appear in the advert. This was disputed by both Marc Hill, who recalled a delay in casting, and Howard Guard, who stressed that Murphy was first choice.

David Sylvian was never considered – Pete was in pole position from the outset.

The legacy of the first advert was that Bauhaus (or rather Peter Murphy) ended up in the film ‘The Hunger’ (Dir. Tony Scott, 1983), as Howard Guard explains.

Maxell led to Pete and Bauhaus featuring in Tony Scott’s first film, The Hunger. I was in business with the Scotts when we shot Maxell. Tony was in pre-production on the film and we used to meet some evenings. It was on one of those evenings he saw Maxell and cast Pete. (3)

Peter Murphy corroborates:

“Howard Guard is the director – he was part of Ridley Scott Associates – a part of their team. He was one of their in-house directors. He had this commission to do Maxell Tapes, and he was looking for a model, and it was a ground-breaking ad. At that time it received awards it was so modern, the idea of this Bauhaus-Peter-black-homoerotic-scary-black-spider-thing.

Howard Guard himself, the director, was obviously speaking to Tony (Scott). He went to him and said “You’ve got to see this”. Because he came to our (Bauhaus) shows and he saw “Bela’ (Bela Lugosi’s Dead).

Ding! Eureka! Ran to Tony and said, “Get here!”. Tony came to the show and went “Oh yes”. (4)

The success of the TV spot, soon led to a sequel the following year.

Advert 2 – ‘Let the Colour Break Through’ + ‘Get the Picture’

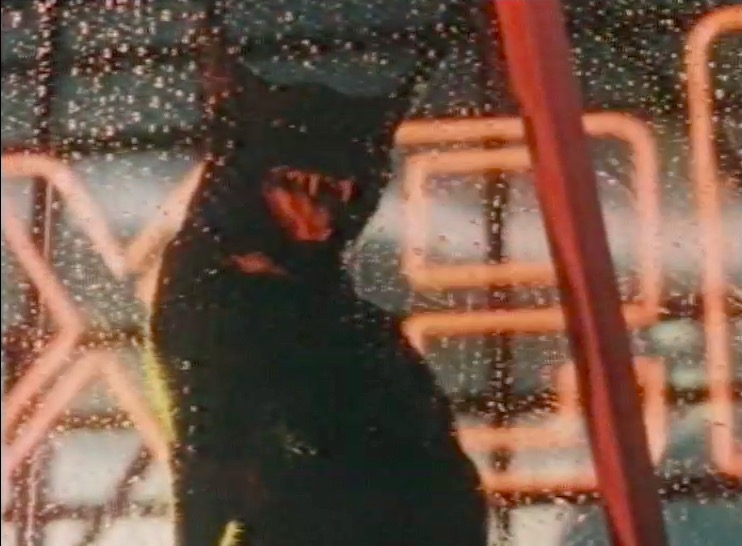

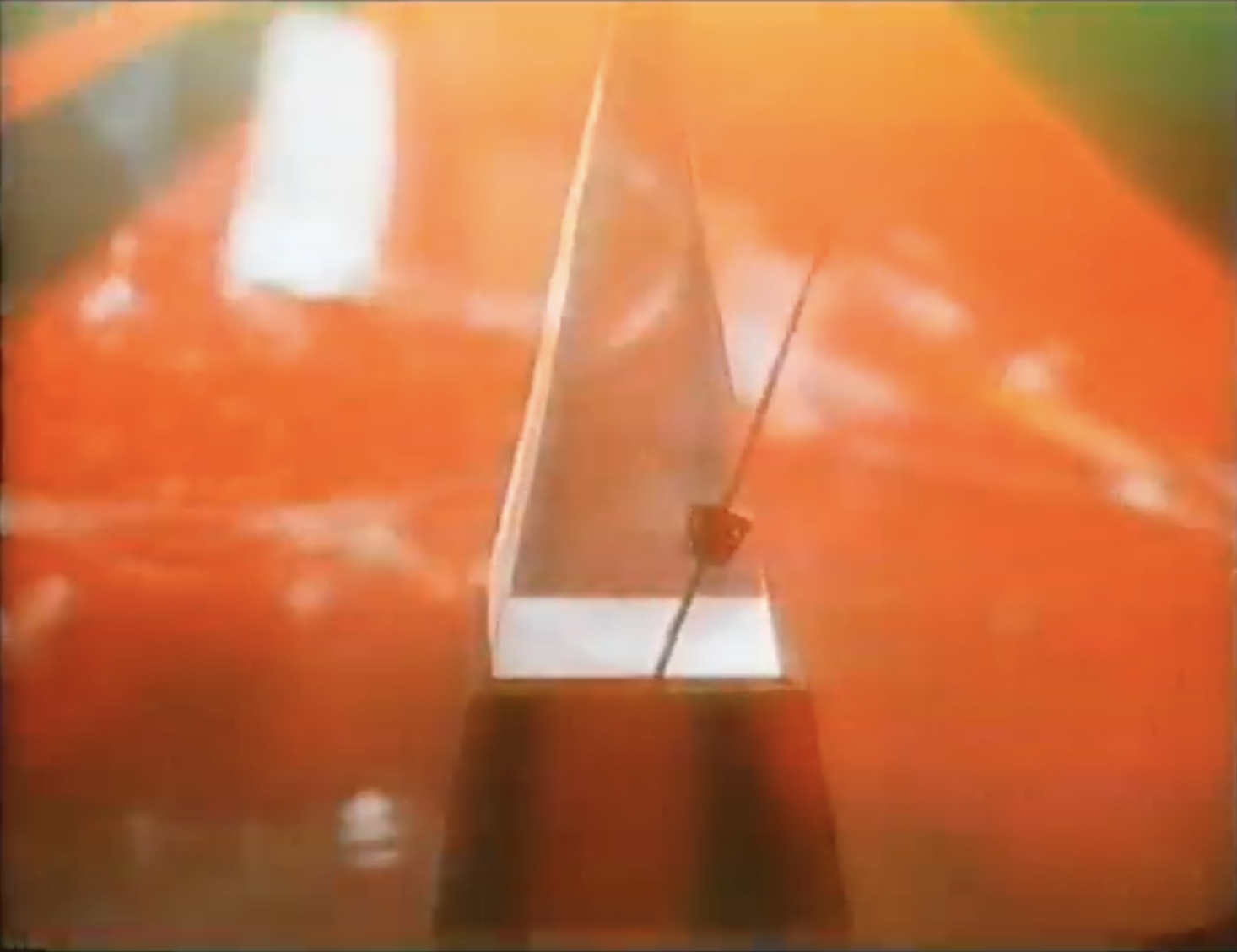

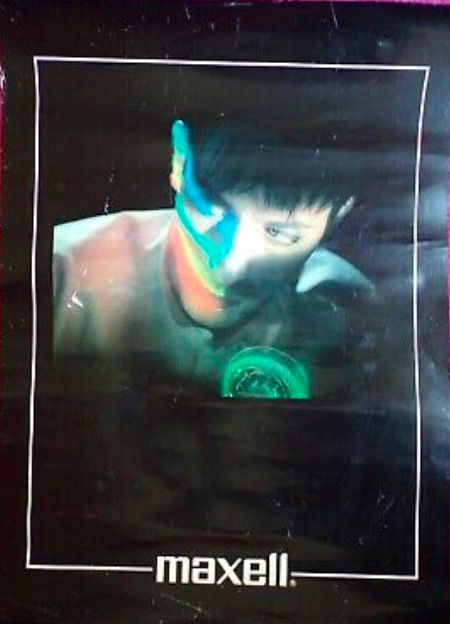

The follow-up commercial for Maxell video tapes, naturally has an even more visual flavour, employing lasers, cats and frogs, whilst retaining the famous Le Corbusier chair, palm tree and Peter Murphy’s glare.

The original advert included the tag line ‘Let the Colour Break Through’, although this was soon replaced by a slightly truncated version, that removed a couple of shots and added a different tagline – ‘Get the Picture’.

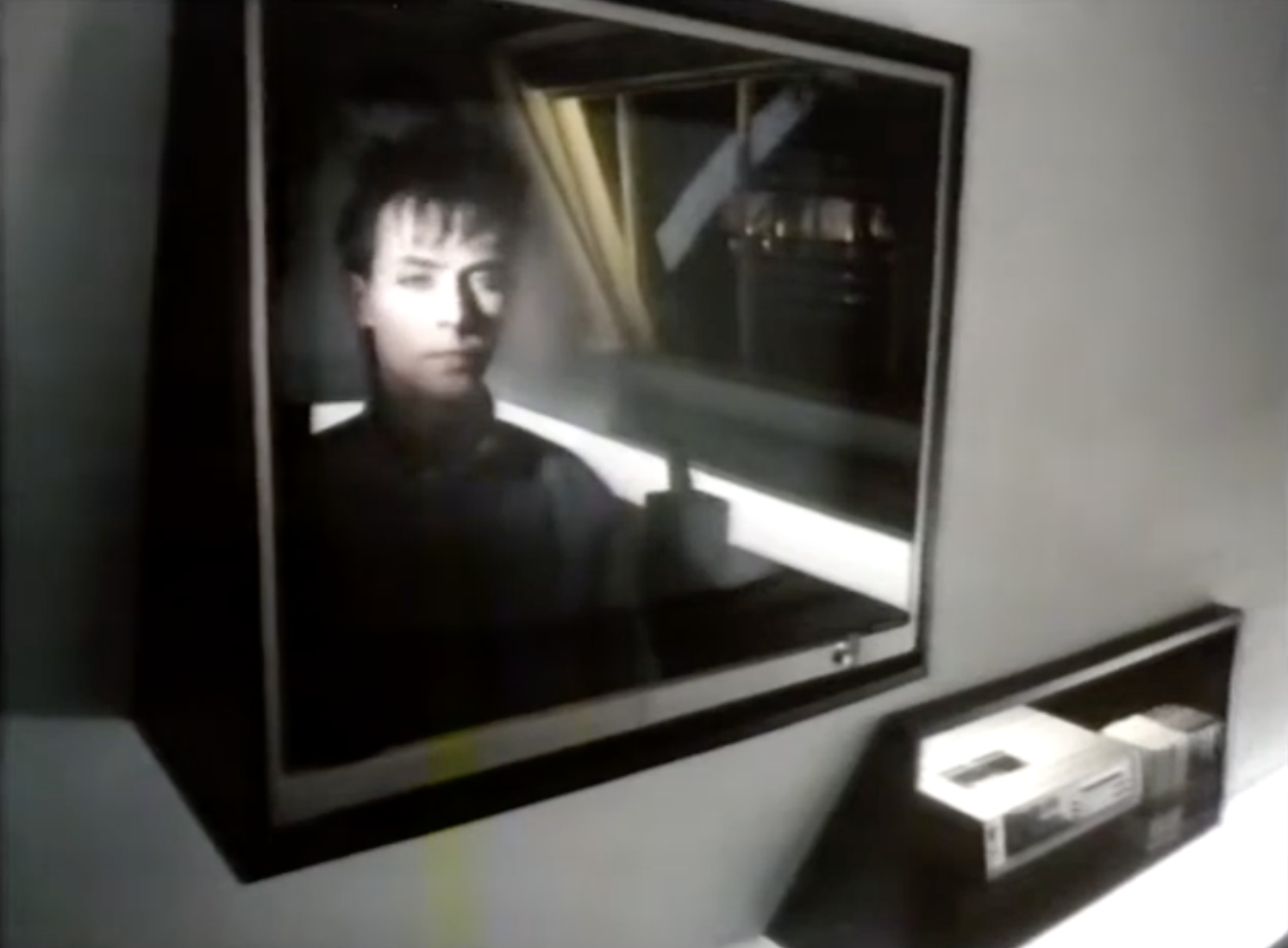

The opening mirrors the 1982 prequel, although a television is now fixed the wall, and a Maxell video cassette illuminated on entry.

This time, the storm is a visual experience, with more than a suggestion of hallucination.

Doctor Who fans will testify that animatronic cats are notoriously difficult to film, but it was a living creature that posed the greatest challenge. Guard noted:

“I shot until 4.00am and 3000 feet of film trying to get the frog to jump with the laser behind.”

Whether the frog jumped or not, the advert had a lasting impact on me. The filmic techniques and physical effects jump out, from the use of colour to the eerie darkness of the very opening shot – a similar darkness that opens another of Guard’s famous works of the early 1980’s – the advert for Fry’s Turkish Delight “Full of Eastern Promise.”

And, as the living room zooms away into the distance, during a rather neat transition to the product reveal and end tagline, Peter Murphy once again cuts the audience another lingering stare.

Guard signed off with:

I remain fond of it.

He’s not the only one. The adverts seemed to be popular with the audience and the younger market that Guard was aiming for. Indeed, Guard felt that this was the best bit of film that he had shot in a couple of years.

It is interesting to note that the was some criticism of the advert from within the industry. This was noted in the contemporary article within Creative Review, which noted how the initial kudos from Campaign magazine shifted to scorn in the letters section, with one insider declaring:

…rarely can so much self indulgence been displayed in 30 seconds.

Guard responded by stating:

It was not an attempt to be arty but to be ballsy.

The article also contained a fascinating take on the lack of award nominations that the Maxell spot generated. It was suggested that its omission from the British Television Advertising Awards was due to its similarities to the American campaign. At the time, Guard defended the accusation that his advert was simply a duplicate.

The [American] SMS film appealed to a sophisticated European-minded, mature audience in a market where Maxell already had a substantial share. We are trying to appeal to a far younger audience and to get Maxell known.

And further to that, there was a cracking quote from Guard, who saw the omission as:

…an extraordinary attempt by the part of the establishment to sink the new wave”.

This culture-clash was something that, even 40 years later, Guard recalled being prevalent at the time.

Guard’s approach was vindicated. The striking imagery served Maxell in the UK well for a number of years, with many a magazine and billboard sporting Peter Murphy, that chair, and the scary house.

And, the adverts served as a springboard to another successful Maxell campaign later in the decade, which was the polar opposite of Guard’s stylisic approach – the confrontational gave way to the comedic.

And in 2009 the advert came third in a top 10 short list for the ‘Greatest Cult Cinema Advert’ ever, compiled by sales house Digital Cinema Media. (6)

Afterword

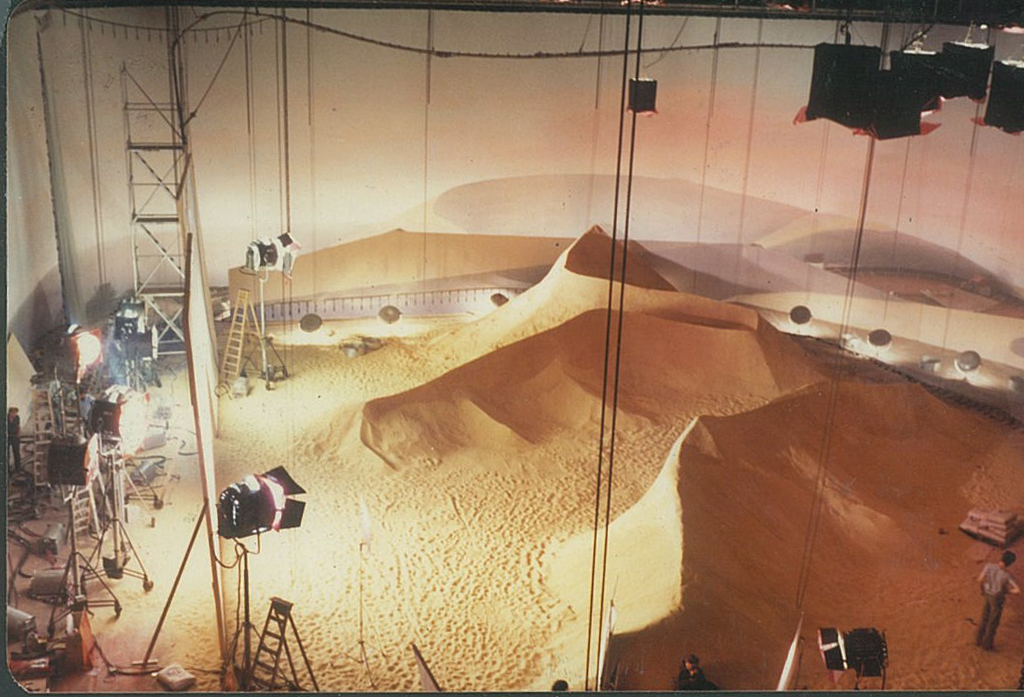

These examples of world-building from Howard Guard are memorable, not only due to the marriage of soundtrack and visuals, but also through how space is realised. His use of light, and carefully controlled camera mask the limitations of the studio boundaries. You can see it in his ‘Maxell’ spots, but also in his ‘Turkish Delight’ advert – ‘Shifting Sands’ for ‘Foot Cone & Belding (FCB, 1981.)

These fascinating photos from Art Director Marc Hill, illustrate the care and attention in which this set was created and lit (on stage A at Shepperton Studios) , and how there was an attention to quality, which coupled with Guard’s determination and skill as a filmmaker, completes the illusion.

Guard would continue to enjoy a successful career – his next steps included videos for Bauhaus – ‘She’s in Parties’ and Roxy Music – ‘Avalon’.

I would suggest that an emphasis on confrontation was a hallmark of the early 1980s. It felt like this gave way to a more elegant and refined approach within television advertising during the midpoint of the decade. Even as a child, I recall the AIDS ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’ public health campaign as feeling less direct or stylised than anything before that point.

Even if any sense of the sharp, style conscious ‘get rich quick’ society continued, it is the first half of the 1980s that I tend to gravitate towards, when I think of the creative explosion that represented this period.

References

(1) https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCyVfhbLNYEj8RT-0zKO82dg

(2) ‘The Sound and the Fury’ – Creative Review, June 1982

(3) Interview with the author. October 2017.

(4) https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/soundcheck/segments/240248-peter-murphy-interview-vampire

(5) https://www.oneclub.org/articles/-view/catching-up-withpeter-levathes/

Leave a reply to The secret story of an iconic TV commercial for cassettes | Alan Cross Cancel reply