Before we talk about anything ‘Old’ and ‘Grey’, let us consider the ‘new look’ – two words that always feel like a mainstay in the book of television terminology. This is the moment when a continuing series sheds its stylistic skin, often heralding a new studio set design, theme music, title sequence, graphic design, and format.

Thinking back to my childhood, when I developed an interest in the mechanics of television production, the anticipation of a new look was a moment of excitement. What would have changed? What would the title sequence look like? Would there be a new theme tune? Why was I unnaturally over-excited, and needing to get out more?

As I got older, more jaded, and less imaginative, I came to the conclusion that a new look – sometimes described as the revamp – was usually only of interest to those who studied television production, or devotees of the show itself.

Briefly, let’s look at a handful of revamps.

A change in a decade is always the perfect opportunity for a refresh. On the 27th December 1979, Michael Rodd said farewell to the 1970s with the annual ‘Review of the Year’ edition of Tomorrow’s World, acknowledging the “familiar but still mystifying collection of titles and the now vintage theme music of John Dankworth.”

It was more than familiar. That theme tune was the true signature of the series, being instantly recognisable and a perfect accompaniment to various fondly-remembered title sequences that moved from pop art sensibilities to time-lapsed lettering. The late-70s title sequence itself was a neat approach, using a series of objects and substances, created by BBC visual effects designer Ian Scoones, and applying them to a simple idea of transformation, by designers Pauline Talbot (Carter) and Richard Loncraine.

As 1980 arrived, Tomorrow’s World was refreshed, with new graphics visible within the sparse studio set, and on overlayed captions. This used a rounded typeface – Isonorm, (a font we will encounter later in this article) that communicated a ‘high-tech’ sensibility.

Most notably, the theme tune and title sequence was all-new. The music, by Richard Denton and Martin Cook, moved away from upbeat brass and woodwind, towards a somewhat eerie and undulating electronic atmosphere. The title sequence, by Haydon Young, was cutting-edge, creating a sense of mystery as the viewer is taken through a series of canyons, eventually revealed to be a brain in the form of a planet. This was achieved through a fibre-optic camera lens and a state-of-the-art motion-control rig supplied by Oxford Scientific Films.

Another long-running BBC series, Top of the Pops, eventually gave any lingering trace of the 1970s the elbow, thanks to a radical overhaul on Thursday 9th July 1981. Although memory suggests the orchestral rendition of Whole Lotta Love was the previous signature tune, recent years had, in fact, ditched a distinct title sequence completely, in favour of a tune from the Top 30 chart, and a rundown from 30 to number one.

The new sequence retained Bob Blagden’s iconic circular logo, but now featured a rapidly edited series of flying records wooshing past the camera in a smoky atmosphere. Created by dropping coloured vinyl discs from height and filmed at a high frame rate, Marc Ortmans’ concept was dynamic, fast-paced, and coincided with an updated presentational style, featuring a new set design, carnival atmosphere in the studio, and a new theme tune – an adaptation of Yellow Pearl by Phil Lynott and Midge Ure.

Sometimes, a new look meant much more than a change in branding and appearance. It heralded a complete overhaul in format, tone, style, and approach.

A good example of this is from 1980, when new producer John Nathan-Turner took Doctor Who into the new decade. He updated the title sequence and commissioned a new arrangement of the theme tune that, in different iterations, had served the series faithfully for 16 years. The tone of the show changed too, with less humour, harder science, a shift in production values, and a more brooding portrayal of The Doctor.

Fast-forward to the second half of the 1980s, and another intriguing rebrand took place in late 1986. BBC Breakfast Time shifted dramatically, following almost four years of leather ‘De Sede’ sofas, woolly cardigans, and steaming filter coffee machines.

This original ‘relaxed and informal’ mix, was a winning format that not only wrong-footed the bookies’ favourite TV-AM in the ratings during the 1983 breakfast war, but remained respectable once the independent channel got its house in order. Within months, TV-AM had ditched its hard-nosed ‘mission to inform’ with a format very similar to the one Breakfast Time adopted in the first place, with Roland Rat, Nick Owen and Anne Diamond steadying its sinking ship.

By the mid-1980s, it was TV-AM that led the ratings battle. With change afoot, one of Breakfast Time’s key anchors, Selina Scott, departed in the early Summer of 1986. With the benefit of hindsight, Scott added the glamour that simply would not have fitted in with the revamp that was to follow.

And so, in November 1986, Breakfast Time was revamped. George Fenton’s gentle theme music, the Sun/Clock face logo, the living room studio, Russell Grant’s horoscopes, the Green Goddess keeping Britain fit, separate newsreaders, occasional music, cookery, and celebrity guests, all disappeared.

In its place, was a stripped-down show, with a new ‘hard news’ driven approach, complete with formal-wear, authoritative (and therefore brassy) theme music, shiny computer-generated title sequence, and a “splendid” wooden desk. There were fewer presenters, a shorter duration, and less variety. The show had moved from one extreme to another. Frank Bough remained for roughly another year, until late 1987, but it was clear to see that his heart wasn’t in the new format of the show, Following Breakfast Time, Bough helmed the Holiday programme, and then…well, I’m sure you know the rest.

Bough’s dissatisfaction was understandable. The title might have remained, but Breakfast Time was now a completely different show. The middle market was lost to TV-AM, and the rebooted show attracted a much smaller, and narrow audience. But what could have prompted this change? Could it have been budget squeezing following a recent license fee settlement with the government? Could it be a desire from the BBC top brass to shift the tone of its programming? Could it be due to a new daytime schedule introduced in 1986? Or could it be the need for a new direction in light of the competition?

Whatever the reason, loyal viewers complained to the BBC’s viewer forum Open Air, but it would appear that the decision and the understanding of the consequences were made very consciously. It set in motion the inevitable change in title to Breakfast News a couple of years later, which was an example of a rebrand in reverse, where the title changed, but the show remained largely the same!

A little detail of the new Breakfast Time format was a seemingly obligatory nod to the format of old, where the hard news would give way to a feature or interview about something softer – a book, a stage play, or a musician touring the UK. This tiny sliver of the show, often acted as the “and finally” item. This sometimes felt like an inconvenience, either being truncated if the running order overran, or a vehicle for Jeremy Paxman’s attempts to hide his disinterest in the subject matter.

Often, this would take place in a corner of the studio, and was a more relaxed affair, with familiar soft furnishings and Venetian blinds – perhaps the ultimate symbol of informality in television set design? This space could be described as a ‘Comfy Area’, but I’m sure no one would have dared use that term in a current affairs show. Yet the impression of informality and comfort in the corner of a studio will be significant, as we will discover later.

The story of Breakfast Time‘s transformation spans the years 1983 – 87. Coincidentally, this was the life span of another dramatically rebranded series – the trials and tribulations of which straddle the line between brave decision making on the part of the production team, and a sense that the odds were stacked against the series continuing, due to budgeting, scheduling, institutional change, and the pressure of trying to compete against another supposedly similar series, on another channel that, stylistically speaking, wasn’t similar at all.

This is the story of the removal of two integral words. ‘Old’ and ‘Grey’.

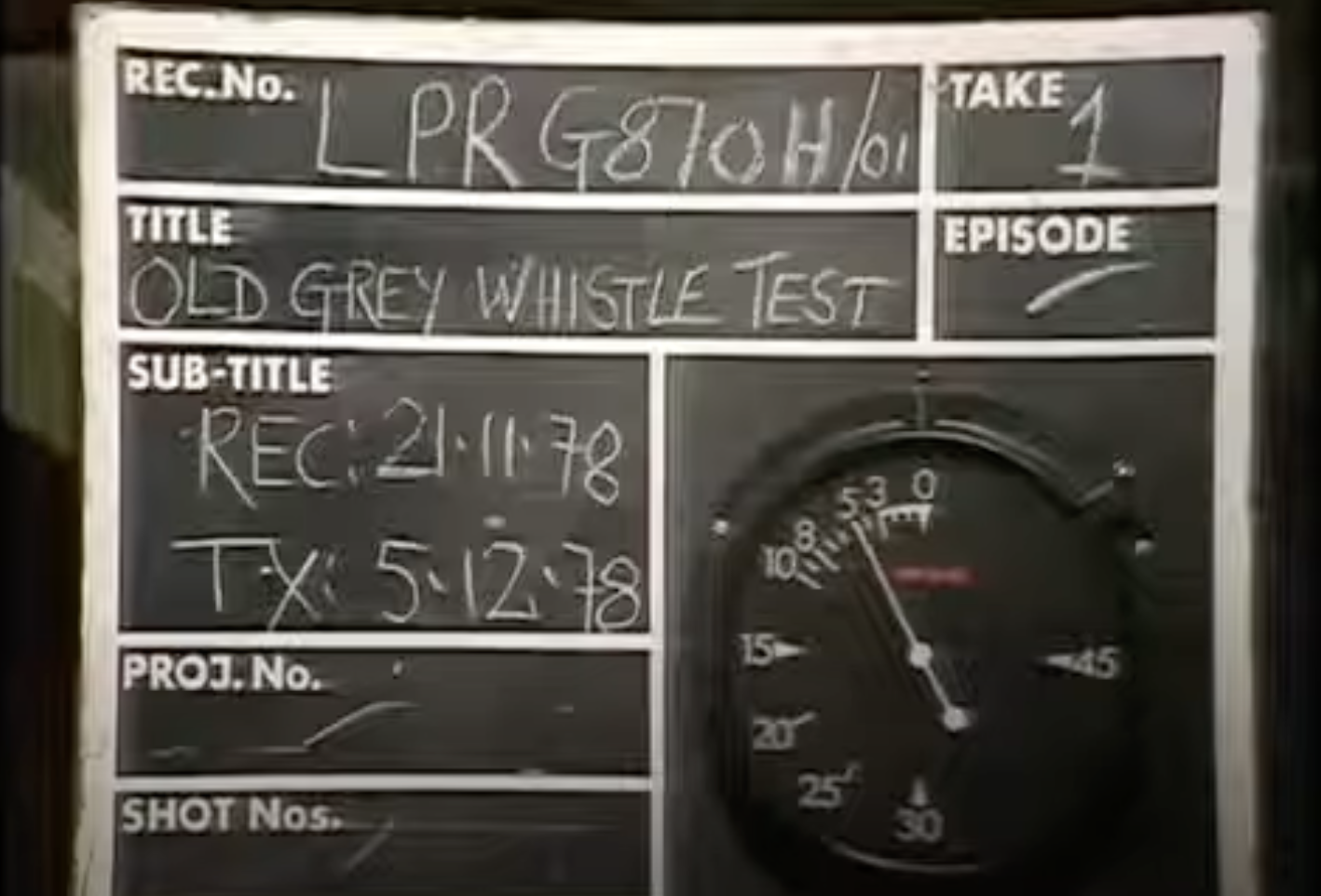

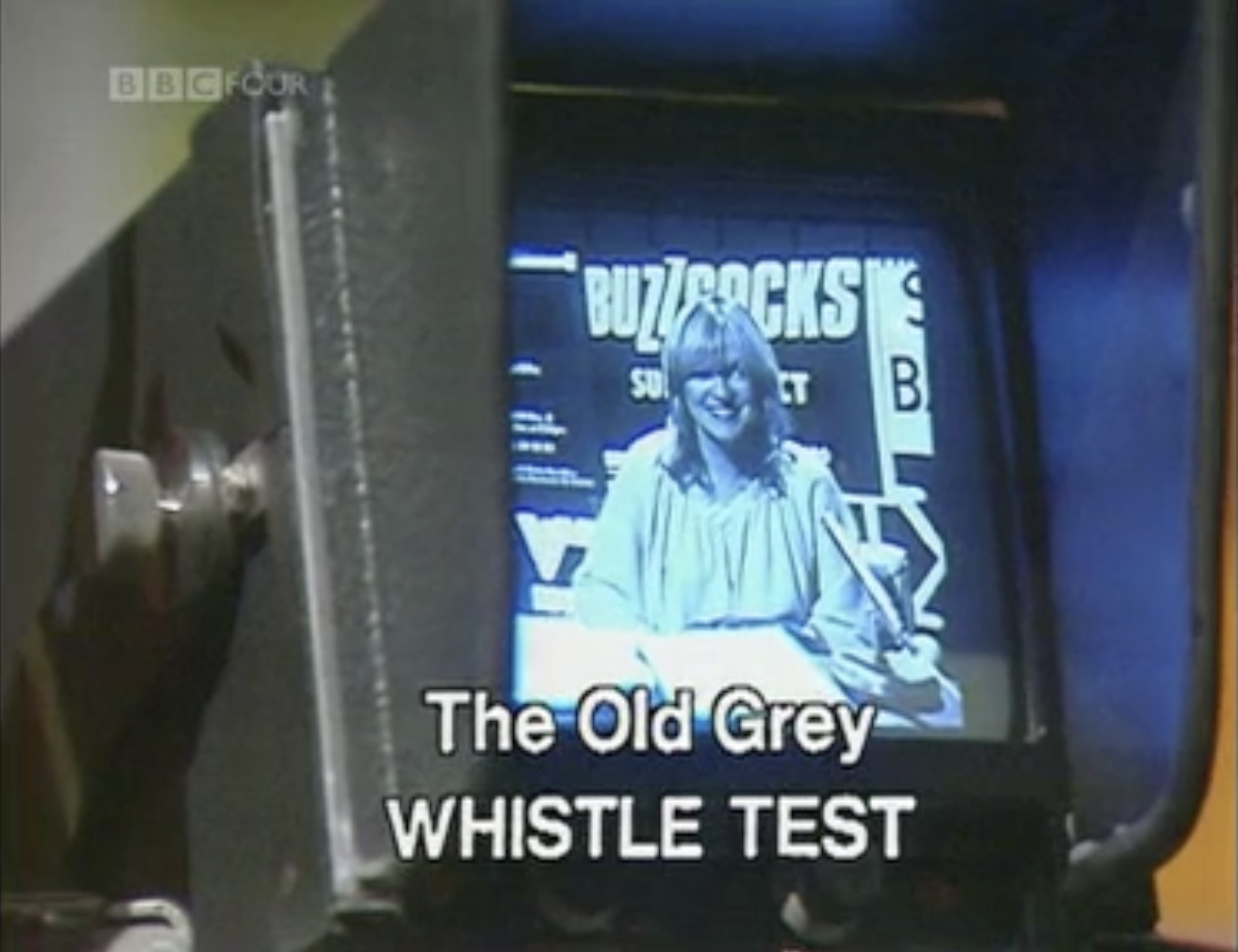

Those familiar with The Old Grey Whistle Test (BBC, 1971-88) will need little reminding of its celebrated history, but a little bit of context is important. You can google the meaning of the title if you want – it’s been explained a million times.

Commissioned by BBC2 controller David Attenborough, OGWT was first broadcast in 1971.

Following on from a series of musical spin-offs from the Late Night Line-Up arts strand, it offered an alternative to the chart-based Top of the Pops, positioning itself as a ‘serious’ music show, helmed by knowledgeable presenters who were drawn from a journalistic background. It often featured musicians and acts that didn’t get much in the way of exposure, and used a narrow magazine format, often consisting of promotional films/video, interviews, filmed reports, forthcoming gig dates, and two live acts performing in the studio.

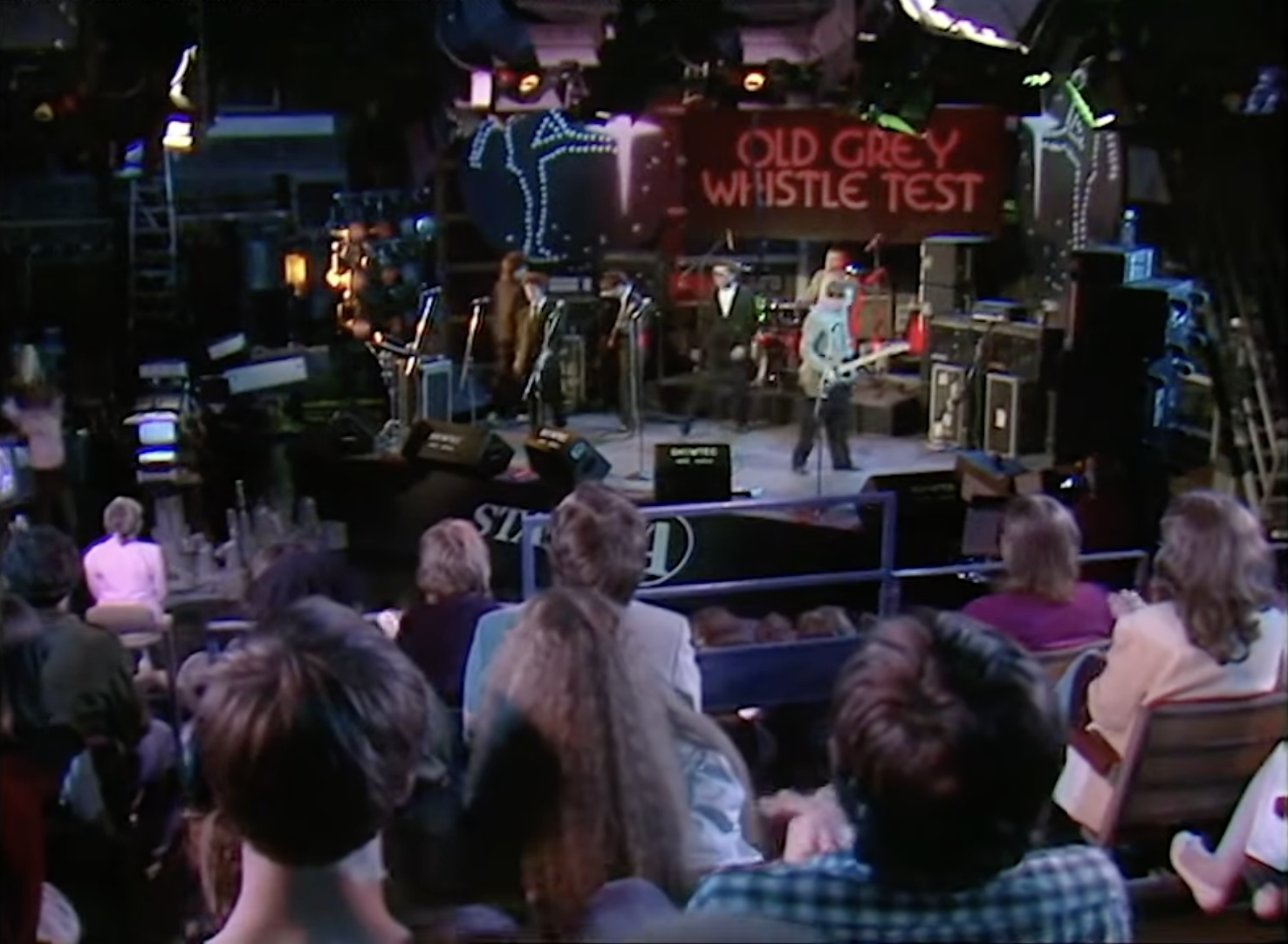

Oh, and the OGWT studio was also famous, featuring minimal set dressing – to say the least. The bare studio wall was the set. Being the last thing broadcast on BBC2 for the day of transmission, it enjoyed a degree of editorial freedom at the ‘cost’ of a minimal budget.

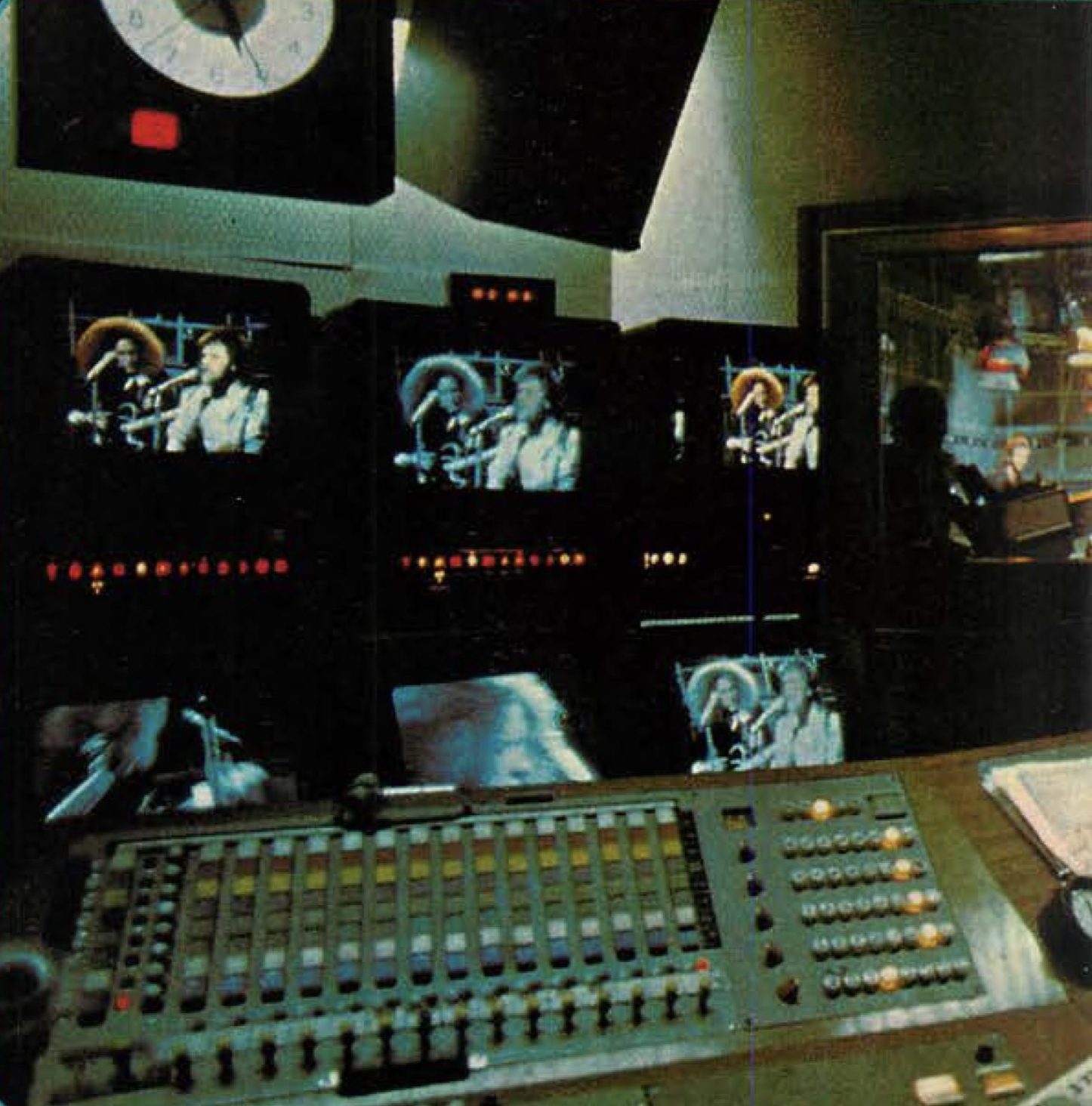

OGWT‘s first home, a tiny studio known as ‘Presentation B’, (or ‘Pres B’) was little bigger than a living room (10m x 7m – OK, maybe a lot bigger), and was used for interviews, continuity links, and the weather. It had eight faders on the soundboard. Somehow, they managed to fit a rock group in there.

Miming to pre-recorded backing tracks soon gave way to live performances, and eventually, the studios got bigger.

Even with more space to play with, OGWT retained its other distinctive characteristic – a lack of a studio audience. This appeared to be a challenge to many performers, who fed off the energy of a crowd. It certainly added to the sense of intimacy, and gave the cold shoulder to any degree of razzmatazz.

Functional, sparse, and utilitarian, OGWT felt anti-style, yet it was often imitated.

The show was initially produced by the ‘Presentation’ department of the BBC, which by the late 1960s, had two distinct areas. Presentation (Production) focused on trailers, continuity announcements, telephone calls for programming etc, while Presentation (Programmes) made programmes, from Late Night Line Up, to Barry Norman’s Film series.

By 1980, Presentation (Programmes) merged with documentary features, into a new ‘Network Features’ department, which was responsible for a range of series, but particularly focussed on cultural programming, from opera performances to long-running television review series Did You See…?

BBC One used to be a network which commissioned programmes from the departments who made the shows, like drama or news or documentary features or musical arts. They were the people who made the shows, and scheduled by the network.

When BBC 2 came along it was argued that they needed a slightly different model, because they wanted to be quicker and more reactive.

…‘Network Features’ was in effect a production department owned by, or at least reporting to the network itself.

Trevor Dann (Producer – Whistle Test 1984 – 87)

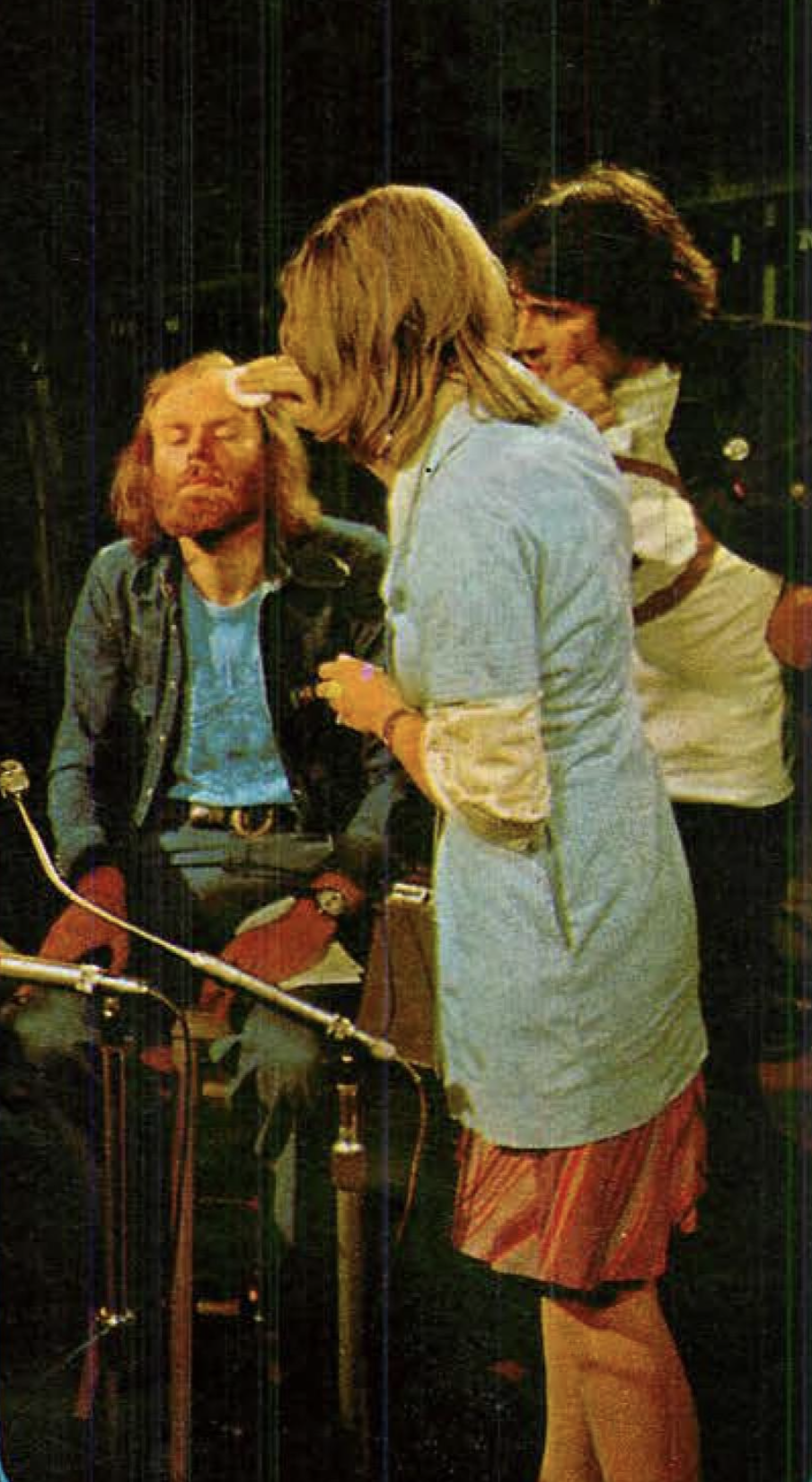

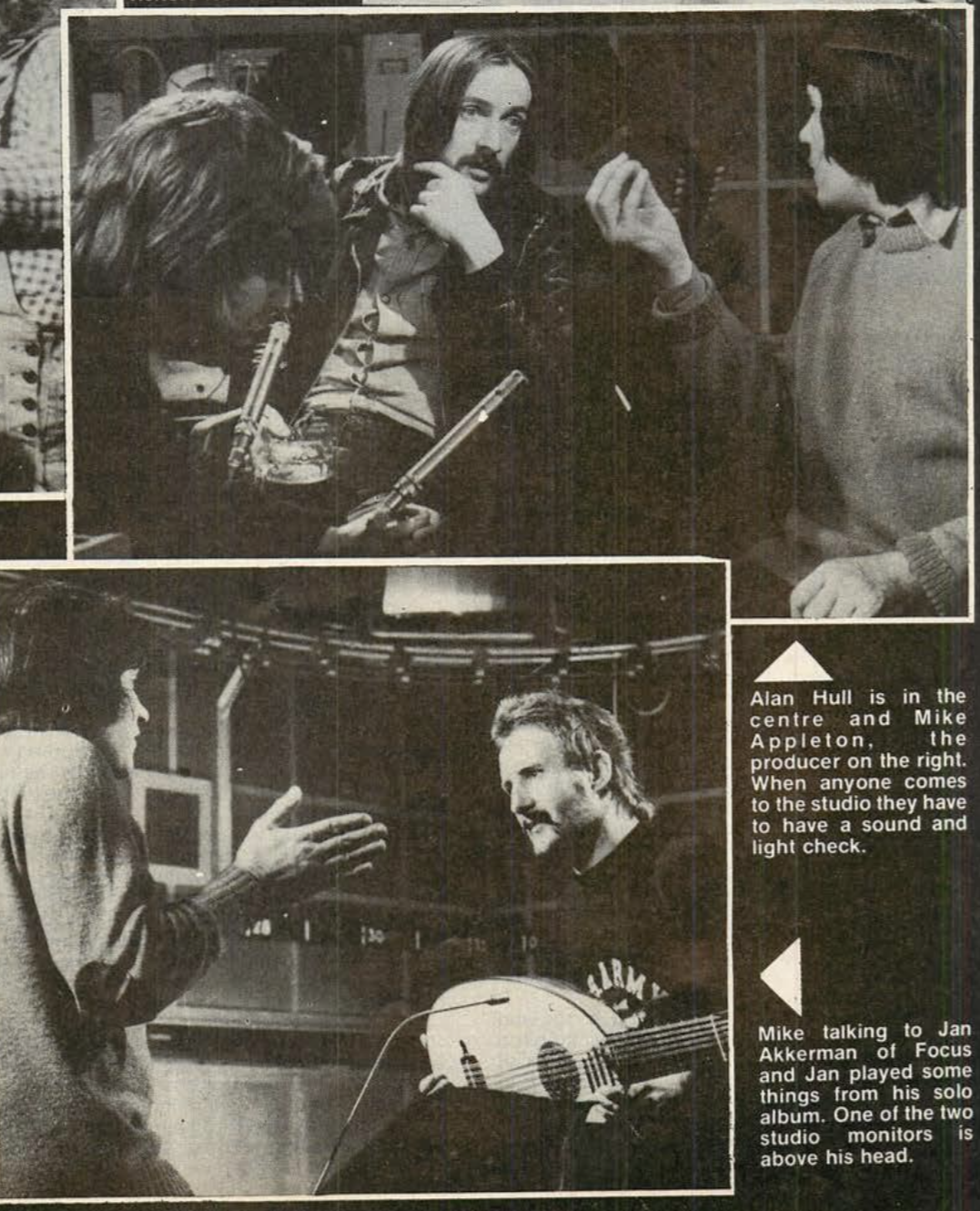

Throughout its entire lifespan OGWT was produced and (later) edited by former Late Night Line-Up production assistant, Mike Appleton, who gave the show a distinct identity, and was the gatekeeper to the show throughout its 16-year run.

Although it was frequently batted around the schedules, the late-night spot was its natural home. Being the last show to be transmitted on BBC2 before closedown, it quickly built a loyal audience.

The choice of presenter was important, all of whom had broadcasting experience, but also journalistic clout. Richard Williams and Bob Harris saw the show through the 1970s. The more introverted Williams lasted one series, before returning to the written page, feeling that his presenting and on-screen interviewing ability wasn’t his natural home. A glance through archival material, suggests this wasn’t the case, as he allowed interviewees space to work around his questions, whether a thoughtful Curtis Mayfield, or an intimidating and volatile Jerry Lee Lewis.

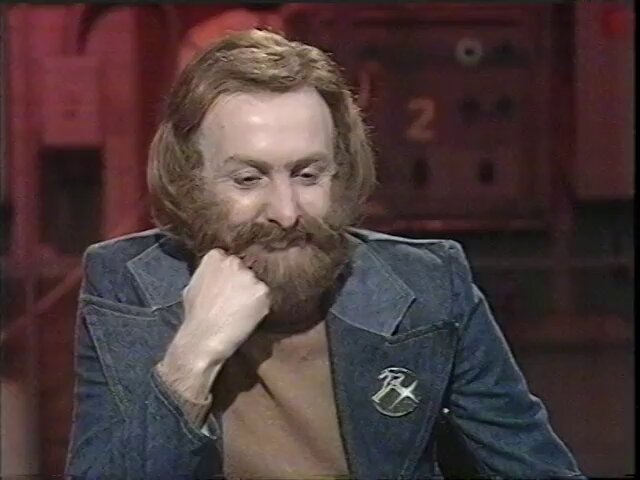

Former Time Out co-editor, Bob Harris, took over in 1972, and became the face of OGWT, finding a natural home in the laid-back surroundings of the show. Often imitated, notably by Eric Idle, Harris could be quite outspoken, with occasional dismissive comments for bands including Roxy Music and proto-punk The New York Dolls.

By the mid-late 1970’s the show had expanded both in terms of bigger studios and off-shoots.

OGWT specials, Rock Goes to College, and Sight and Sound in Concert were a part of the OGWT family. It would appear that the challenges of synchronising both sight and sound, – the live visual broadcast, and the fidelity of radio – required a simple and labour intensive solution.

The sound engineer sat in Broadcasting House, wearing headphones, with a feed of the television sound in one ear, and the stereo radio in the other, and kept things in synch with a vari-speed control.

John Burrowes – Producer and Director of OGWT/Whistle Test.

OGWT clocked up some road miles too. A lack of scenery – and therefore a lightweight traveling set – resulted in frequent editions coming from BBC Bristol (think Stackridge), BBC Glasgow (think The Sensational Alex Harvey Band), BBC Manchester (think John Cooper Clarke) and BBC Pebble Mill (think Judas Priest, or the first punk band to appear on OGWT – The Adverts).

And it was punk that offered the first challenge to OGWT‘s ongoing relevance. In February 1978, The Adverts finally broke the mould, with T.V. Smith taking the microphone and announcing “At last, the 1978 show” in recognition of the show’s perception in some quarters. So, while history might tell us that OGWT was slow to embrace the new music scene, it did move with the times once the 12-inch albums were released (the show eschewed 7-inch singles).

That particular edition was also notable, as it was the debut of Annie Nightingale as a one-off host. This was due to a late change in transmission dates, meaning Bob Harris was unavailable.

At the beginning of the 1978-79 series, Bob Harris’ role was reduced, mainly offering pre-filmed inserts, while Annie Nightingale took on permanent presenting duties, offering a playful banter with a new wave of acts.

The show remained largely unchanged in format, apart from an increase in music discussion, cinema, and literature. And there appeared to be a very slight increase in irreverence, possibly down to Nightingale’s wry sense of humour.

I thought I might be sounding too flippant. I write all my scripts, and tried a slightly different approach.

Annie Nightingale (unknown archival interview – 1981)

When the host welcomes you to another edition of OGWT, wrapped in layers, claiming to be broadcasting from Siberia rather than Shepperton, you know the music is everything, and the style plays second fiddle.

NIGHTINGALE: (TO CAMERA)

Hello, welcome to Whistle Test, coming to you from Siberia.

Well, Shepperton actually, but it’s close.

Or…

NIGHTINGALE: (TO CAMERA)

Tonight, The Beatles, who have decided to reform and are with us in the studio…

…which is a complete lie, but I’ve always wanted to say it.

The minimal style (or scenery) OGWT had was very distinctive. A review of any archival footage from the mid-1970s onwards will rightfully showcase the performance, but our eyes will glance upon a very familiar and simple set design – a rectangular board with the words ‘OLD GREY WHISTLE TEST’ and to the fringes, two circular hangings featuring the show’s emblem, the ‘Starkicker’ – a feature of the title sequence from the very beginning, and a symbol that was enigmatic enough to not suggest one thing nor another.

By the early 1980s, OGWT was cemented as a mainstay in the music television landscape, both in the public consciousness and in the scheduling of the show. Bar a few months in the summer, OGWT was broadcast weekly for around nine months of the year, building up a substantial archive that is enjoyed by many today.

But of course, we’re not here to wallow in a show that is secure, constant, and sure of itself.

In 1981, OGWT celebrated its 10th anniversary. However, times they were a changing…

Here is a little article about the BBC’s annual report covering the 1982-83 financial year. It’s from The Daily Telegraph, so naturally it’s going to use the BBC’s own reflections as a stick to beat it with.

It’s quite amusing in many ways. It claims “well-tried formulae are no longer good enough“. Yet, in the same breath, it faults a new approach to The Hound of the Baskervilles as “not quite reflecting the generally preconceived ideas of the two characters“.

Elsewhere, it notes the need to keep schedules fresh, the competition from Channel 4, and the emergence of the video cassette. We’ll be paying attention to all three of these factors during this article.

I imagine it would take a brave team to radically disrupt a “well tried formulae“, without justifying a need to do so. Yet, around this time, the OGWT production team would no doubt be looking over the shoulder of a significant increase in music television competition. There were also changes within the BBC itself, following a recent license fee settlement and charter renewal.

Although the really big change wouldn’t happen until 1984, the preceding years clearly demonstrate that OGWT didn’t shed its skin overnight. Let’s dive into the gradual changes over three series in the early 1980s.

The first notable change occurred during the 1981-82 series, broadcast on Thursday late at night, and the last to feature Annie Nightingale. For the first time, OGWT incorporated a studio audience. Prior to this series, the lack of audience (bar the occasional special, often filmed at the BBC Television Theatre in Shepherds Bush) was part of the distinct flavour of OGWT, showcasing musicianship over audience appreciation.

However, the days of the one-off live performance special were numbered. Or rather they were migrating into the sister show Sight and Sound In Concert. A 1981 concert from Stanley Clarke and George Duke appears to be the last one from BBC theatre, with further one-offs, such as Todd Rundgren and The Teardrop Explodes, coming from Television Centre and Riverside, both in 1982.

I had a degree of reservation about introducing an audience. I could see that it was a major improvement for the interaction of the bands that were playing live, but I thought from the audience’s point of view in the studio, there were long periods where there were sequences going on in interviews, and filmed reports that really were not enormously entertaining to be sitting in a studio for.

I think it was worth it in the long run because it did make the bands feel more at home. They had something to play to, rather than the cold studio, and although some people might have thought this detracted for the bands playing for the audience at home, I think what would happen in the long run is you’ll get a better performance out of the band, and that benefited everybody.

Mike Appleton (BBC DVD Commentry)

Appleton also noted how uncomfortable it would be for the audience to look up at the TV monitors high up in the lighting grid, in order to see the inserts and features that made up the show. There was also another challenge that stemmed from standard BBC procedure of the time.

One of the pitfalls of introducing an audience was that they got their tickets via applications to the BBC ticket unit, and the applications were issued on a first-come first-served basis, and not really related to the content of the programme.

To come and see a television programme being made in principle works out quite well, but it doesn’t always work out. We had one occasion where a coach load of elderly matrons from the Midlands suddenly appeared in the Whistle Test audience and everybody was sort of whispering “What’s happening?” “Who’s that?” In fact, they probably had applied to go and see Val Doonican but they got tickets for Whistle Test.

I always remember the horror on their faces when the first band started playing. As soon as the session finished and we’d gone into the first pre-recording – it was a film interview – they all got up and trooped out as quickly as possible.

As a result of that, we developed a close relationship with the ticket unit and had some influence into exactly who was given the tickets. In fact, we asked people to only apply if they wanted to come and see the programme, and we never had that mix up again.

Mike Appleton

A good example of this is from an edition in April 1982, where Clint Eastwood & General Saint performed ‘Another One Bites the Dust’ to the full spectrum of the populace – from those at one with the music at ground level, to those in the upper rows who seemingly hadn’t much of an idea – notably a disapproving looking woman and a baffled looking security guard.

Nonetheless, a studio audience finally gave the musicians something to respond to, and added a little extra atmosphere to the freezing cold Riverside Studios, or wherever in Siberia the show was recorded during that particular week.

This period of the show saw some new faces within the production team. An important addition was production assistant Karen Rosie, who would be a mainstay until the very last edition

I was on the TV Production Panel as a PA (Production Assistant). The studio and filming part of the role is nowadays called Script Supervisor. Being on the panel meant you were allocated to different departments for a period of time. I worked on Tomorrow’s World, The Risk Business, Jackanory.

I asked to go to the Whistle Test when a place was available, and eventually became permanent in the Network Features department which made the programme.

PA in those days in Network Features meant organising logistics – booking studios, crew, presenters, contracts for bands, breaking down the music for bands appearing, typing script, assisting Director and Vision Mixer in the studio gallery/OB by bar counting and timing programme, organising and going on filming trips where required, outside broadcasts, budgets, post production paperwork, and any other admin.

Karen Rosie

Another significant addition to OGWT was in front of the camera – namely, the introduction of David Hepworth, a record plugger and editor of Smash Hits. Hepworth made his debut in early 1981, having convinced Mike Appleton that he would make a good addition to the OGWT team during a chance meeting at a Bruce Springsteen party in New York in December 1980.

I had drunk enough to suggest that he really should hire me on the “Whistle Test”. A couple of weeks later he rang and asked me to come and review some music books.

David Hepworth (a tribute to Mike Appleton, 2020)

By the 1981-82 series Hepworth was co-presenting with Nightingale. Hepworth had the essential attributes of an OGWT presenter – journalistic experience, and the confidence to be opinionated. His rise up the ranks to become the youngest ‘elder statesman’ presenter ever, was complete within 18 months.

OGWT had never used two co-presenters, and their on-screen personalities complemented each other. Off-screen too, the working relationship was harmonious. In an edition of the Word in Your Ear podcast, Hepworth recalled how welcoming Nightingale was.

(Annie) could not have been kinder to me, she could not have been nicer. You know people ordinarily in those kind of positions, you know TV presenters or radio presenters, as a breed they they’re paranoid because their fame always hangs by a thread, …they’re all paranoid for good reason.

But Annie wasn’t at all. She could not have been nicer and more accommodating.

David Hepworth (‘Word in Your Ear’ podcast, 2024)

As a woman in the music industry at the time, Annie Nightingale was an inspiration and a great presenter. She knew all the bands old and new and encouraged new talent. David Hepworth was already there when I arrived. He was editor of Smash Hits at the time, knew his stuff, had encyclopedic knowledge of music, and a good sense of humour.

Karen Rosie

Indeed, Nightingale also received the same treatment as Bob Harris, as OGWT was parodied by Not the Nine O’clock News.

Annie Nightingale left OGWT as a regular presenter at the end of the then-current series, in June 1982. History doesn’t record the reason for her departure. Contemporary press clippings suggest that it was a decision made by the production team to replace the presenter. Yet, Nightingale suggests it was time for a change, a view that lends weight, given that Nightingale contributed to a film insert in the next series, reunited with the OGWT team to host a live rock marathon, and maintained a strong appreciation for Mike Appleton in the years that followed.

Perhaps mutual benefit is the headline; a decision that allowed the show to move into its next era.

1982 was a significant year for OGWT. The show took its regular summer break following Annie Nightingale’s final show in June. Upon its return to the schedules in September, it boasted several new ingredients that suggested evolution, rather than reinvention.

Firstly, there was another new timeslot – this time late on a Friday. This would be the slot that the show would occupy for the next three series, perhaps hoping to catch a more lubricated audience who had saddled out of the drinking holes. An early evening Saturday repeat would be available for those who had not staggered home in time.

Next, there was a new presenter. Journalist and fellow Smash Hits editor, Mark Ellen, joined his friend and colleague David Hepworth. Ellen had recently stepped in as holiday cover at Radio 1, when Mike Appleton dropped in to see if a switch to television was on the cards. A bank holiday rock special on BBC2 – hosted alongside Hepworth – was his televisual presenting debut, and a regular gig on OGWT followed.

Together, Hepworth and Ellen quickly became something of a double act – a first for the series. Their ease with each other can be seen in the opening show together, where Hepworth describes Ellen as “a long leggy person“, and within minutes makes reference to a frequently commented resemblance to Paul McCartney.

Another change was in the title sequence and theme arrangement. As noted earlier in this article, both can become synonymous with the show. In this case, Stone Fox Chase by Area Code 615, had accompanied the OGWT title sequence since the very beginning.

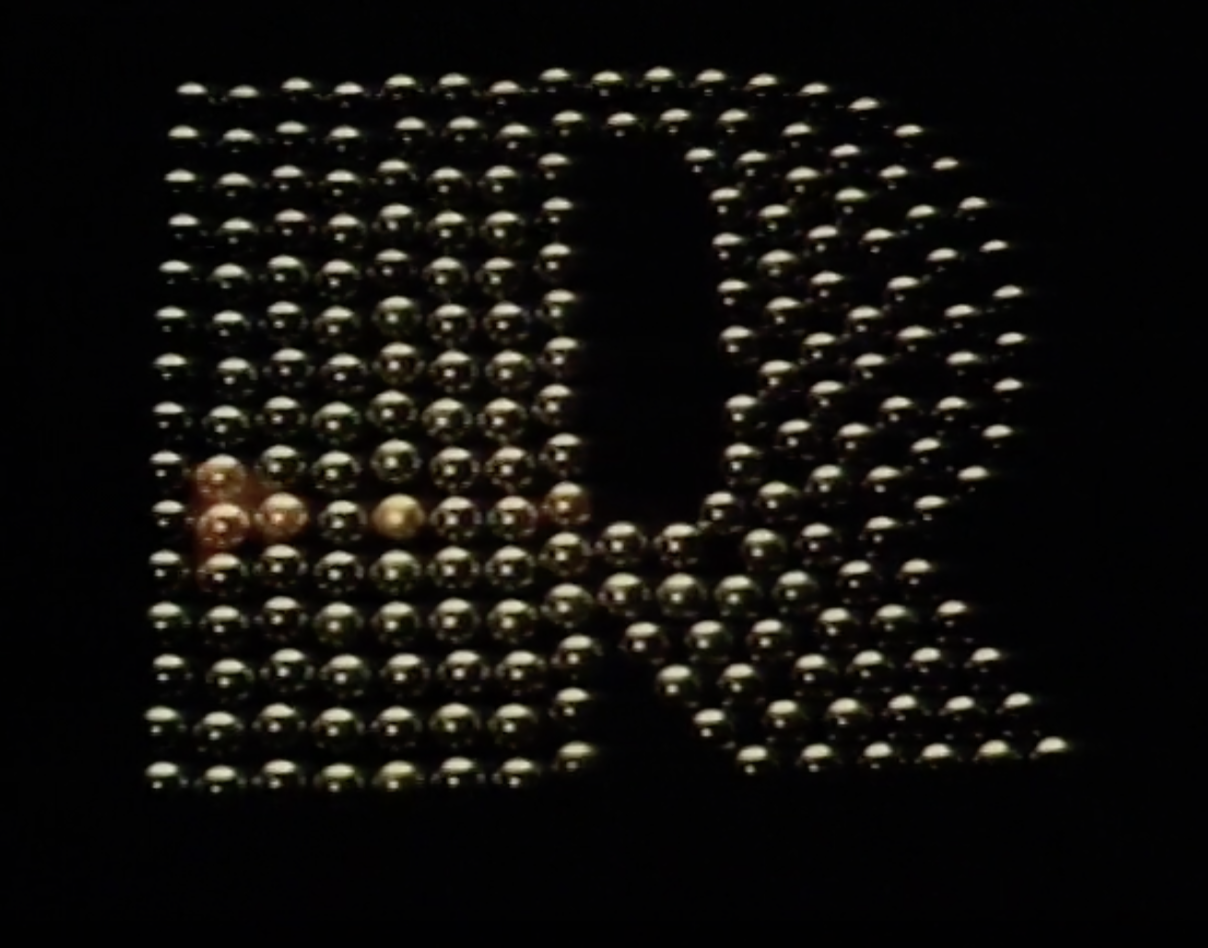

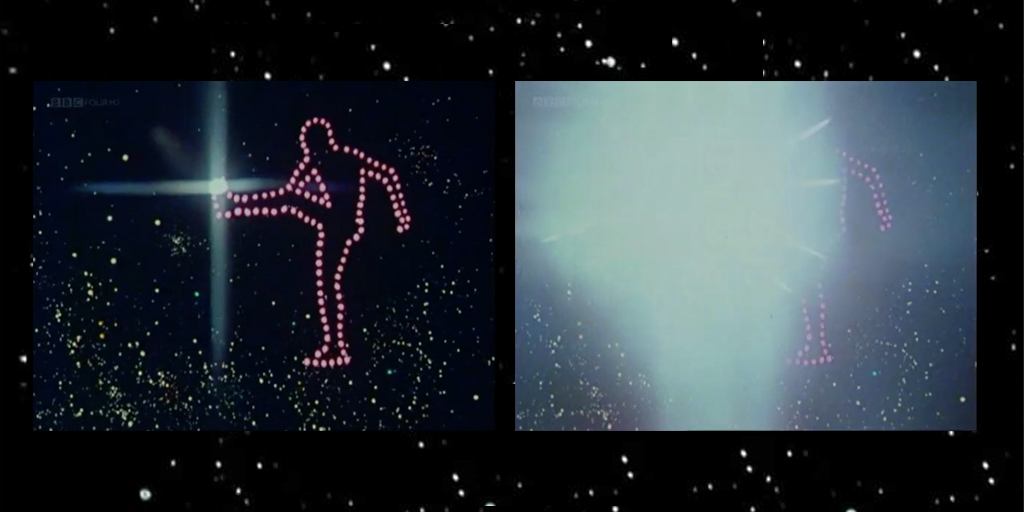

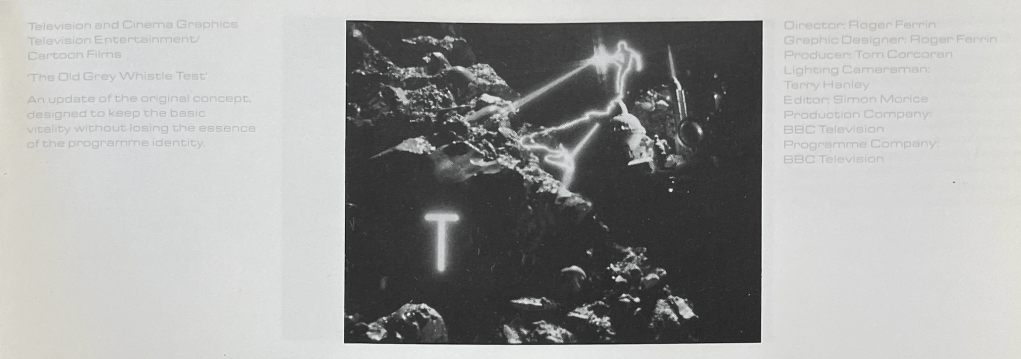

The original decade-long, award-winning sequence was created by BBC designer Roger Ferrin, and removed direct references to music, in favour of a symbolic representation of what OGWT could possibly be about. Most famously, a figure that emerged from space – the ‘Starkicker’ – became the ultimate visual motif of the show, and featured everywhere, such as album covers, badges worn by the hosts and guests on the show. Of course, it featured prominently in the sparse set design in studio.

The new title sequence, also designed by Ferrin, once again favoured a symbolic representation of the show, referencing space-age futures, crackling energy, and arcade-game details. It featured what appeared to be craggy rocky surfaces being ‘zapped’ by what looks to be a speaker-like setup, embedded within the mountainous terrain.

The logo was also given a new twist. The original ITC Busorama Bold title, released on the commercial market the year before OGWT was first broadcast, was replaced by a suitably 1980s rounded typeface – Isonorm. With the benefit of hindsight, it was not as memorable.

We changed our opening title sequence. So, the Starkicker – who was like our signature and so associated with the programme – virtually disappeared. It was kept on just slightly but it certainly didn’t have the predominance that it had at that time.

Mike Appleton

To be honest, I haven’t the foggiest idea what is going on in the sequence, although I do know that it is intriguing, in that it acts as an update to OGWT, rather than a fresh start. It references the history of the show, (including the ‘Starkicker’) while also nodding to the present day. This is supported by the fact that the Stone Fox Chase theme is retained, but now synthesised (cheaply, in my opinion).

Nonetheless, the sequence was shortlisted for a D&AD award, and maintained OGWT‘s enigmatic traditions.

And, the show’s title was the focal point of another noteworthy change. This could be found within the set design of the new series – the removal of the rectangular banner at the rear of the stage, with the words ‘OLD GREY WHISTLE TEST’.

The disappearance of this title banner, while retaining the two circular ‘Starkicker’ logos, could be down to the change in logo seen in the new titles, or it could suggest that the production team might have become slightly self-conscious of the words ‘Old’ and ‘Grey’ within the programme’s title. Perhaps there was an eye on a new programme, that could conceivably give OGWT a run for its money?

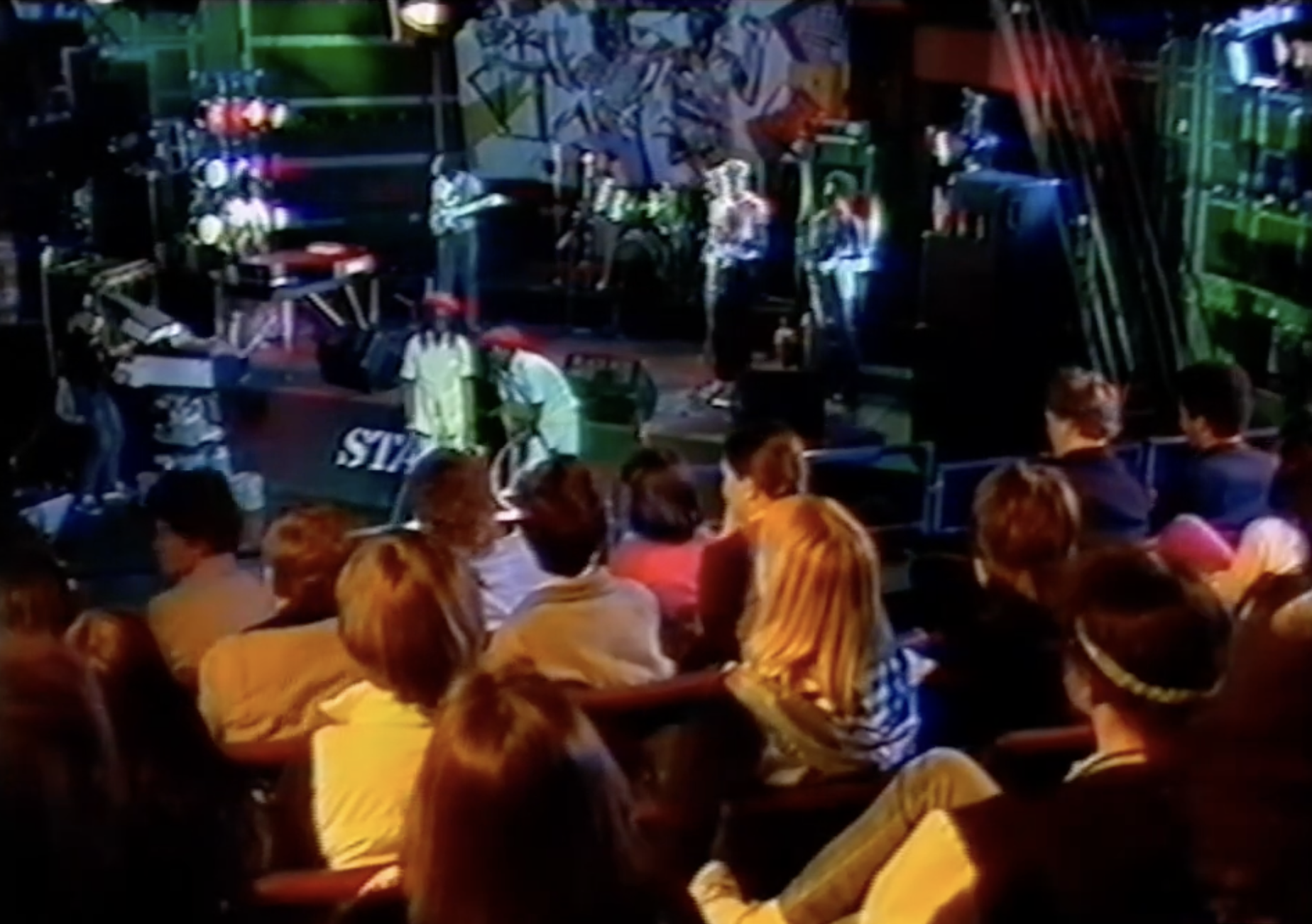

When the history of OGWT is discussed, the introduction of The Tube (Channel 4, 1982 – 87) is often referenced as the main reason for the challenges faced in those final years. This is supported by the viewpoints of the key members of the production team, alongside the regular hosts.

It’s certainly a point where the course of ‘feature’ rock music television (i.e BBC vs commercial television) splits into two. The Channel 4 series, with its high octane, high production values, and a sense of things spiraling out of control, was everything counter to OGWT‘s sensibilities.

It’s interesting to watch the early episodes of The Tube, where technical glitches and ad-hoc delivery were celebrated – a whiff of televisual revolution could be smelt in the air. Meanwhile, OGWT maintained a degree of control and formality, with the presenters seated in front of the stage, and reckless abandon confined to a darting Peter Murphy, and malfunctioning guitar belonging to Daniel Ash, during a Bauhaus performance of Ziggy Stardust.

Yet, it was the scale of the two shows that was most noticeable. The Tube had an increased timeslot, approximately double that of OGWT, and with that, more live bands. Bigger apparently meant better.

Although MTV launched in 1981, The Tube commenced its run mid-way through OGWT‘s Autumn 1982 series, so it is possible to conclude that the subtle changes seen in the first Hepworth and Ellen series, and the following run between April – June 1983 was not a direct reaction to the increasing competition. However, the downplaying of the ‘Old’ and ‘Grey’ might have been considered if Mike Appleton and the production team were keeping an eye on the mid-teen to early 30s market favoured by MTV and The Tube.

Perhaps the changes seen in 1981-83 were more a case of a long overdue evolution of the OGWT format, alongside an emerging reallocation of budgets and scheduling that could be reflected in the decision – for the first time in OGWT‘s history – to truncate the series. The result was that both Autumn 1982, and Spring 1983 series didn’t run for the traditional nine months, but now ran for less than a quarter of a year.

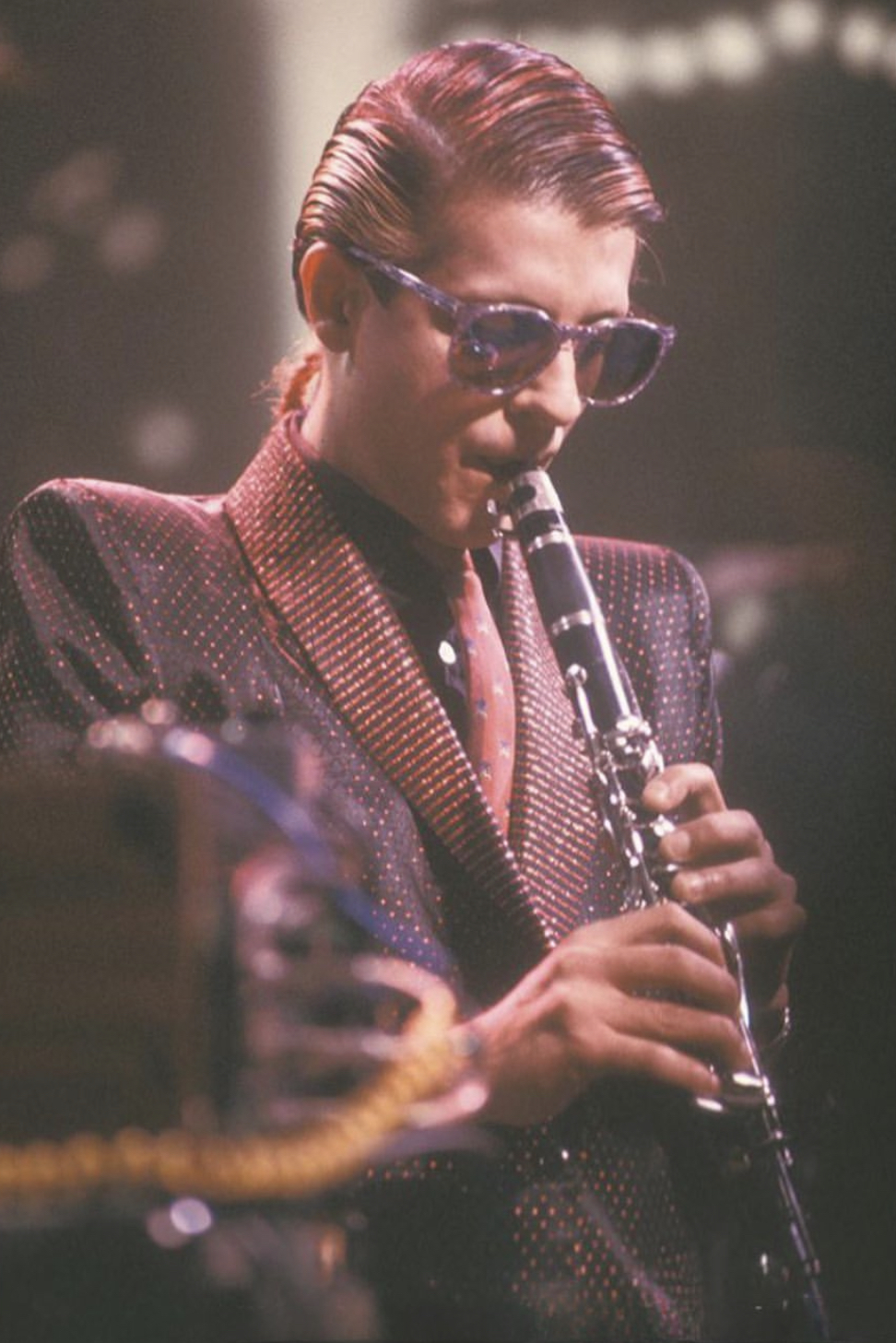

For the casual viewer, there probably wasn’t much of a noticeable change. The studio was still dark. The ‘Starkicker’ set design still hung over the proceedings, and the emphasis was still on live performances, which maintained OGWT‘s eclectic traditions, with some stellar performances including: Bauhaus, Eurythmics, Robert Wyatt, and Japan.

Although 1982 and 1983 might have seen a reduction of the series, there were several OGWT ‘strands’ transmitted – the new regular three-month run, spin-off series Sight and Sound In Concert (no doubt keeping the Regal Theatre, Hitchen afloat), one-off special editions and concert specials, and towards the end of the year there was Whistle Test On the Road – a series of six concerts recorded at venues around the country. It’s interesting to note the title of this short series – there is no reference to ‘The Old Grey’.

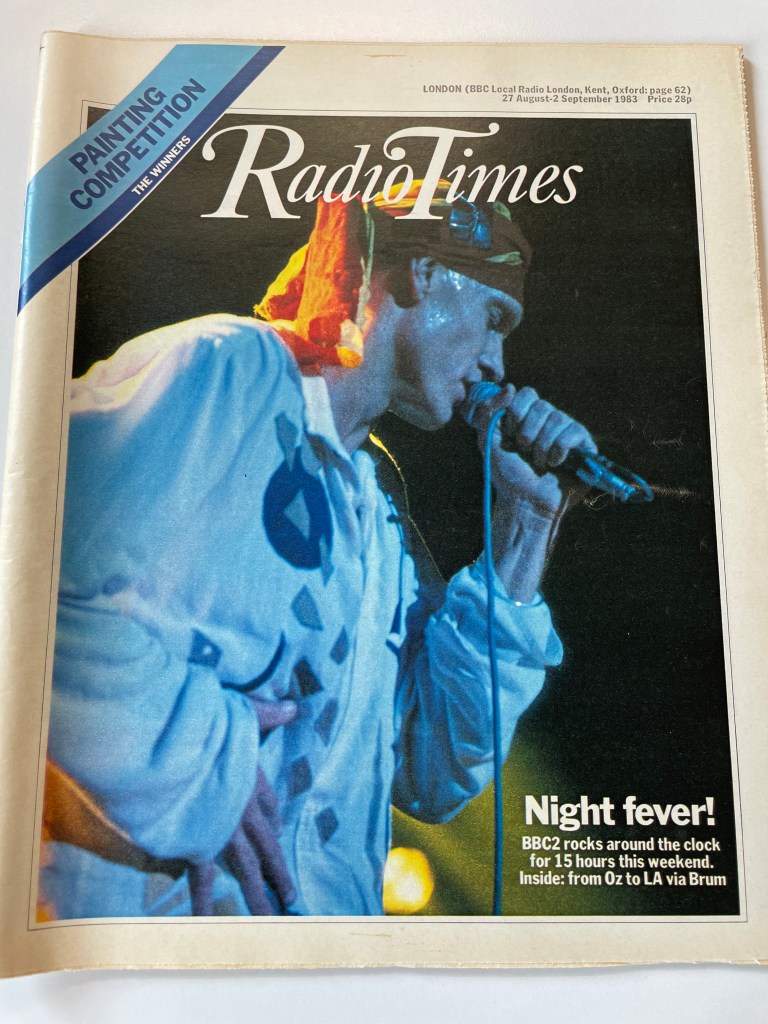

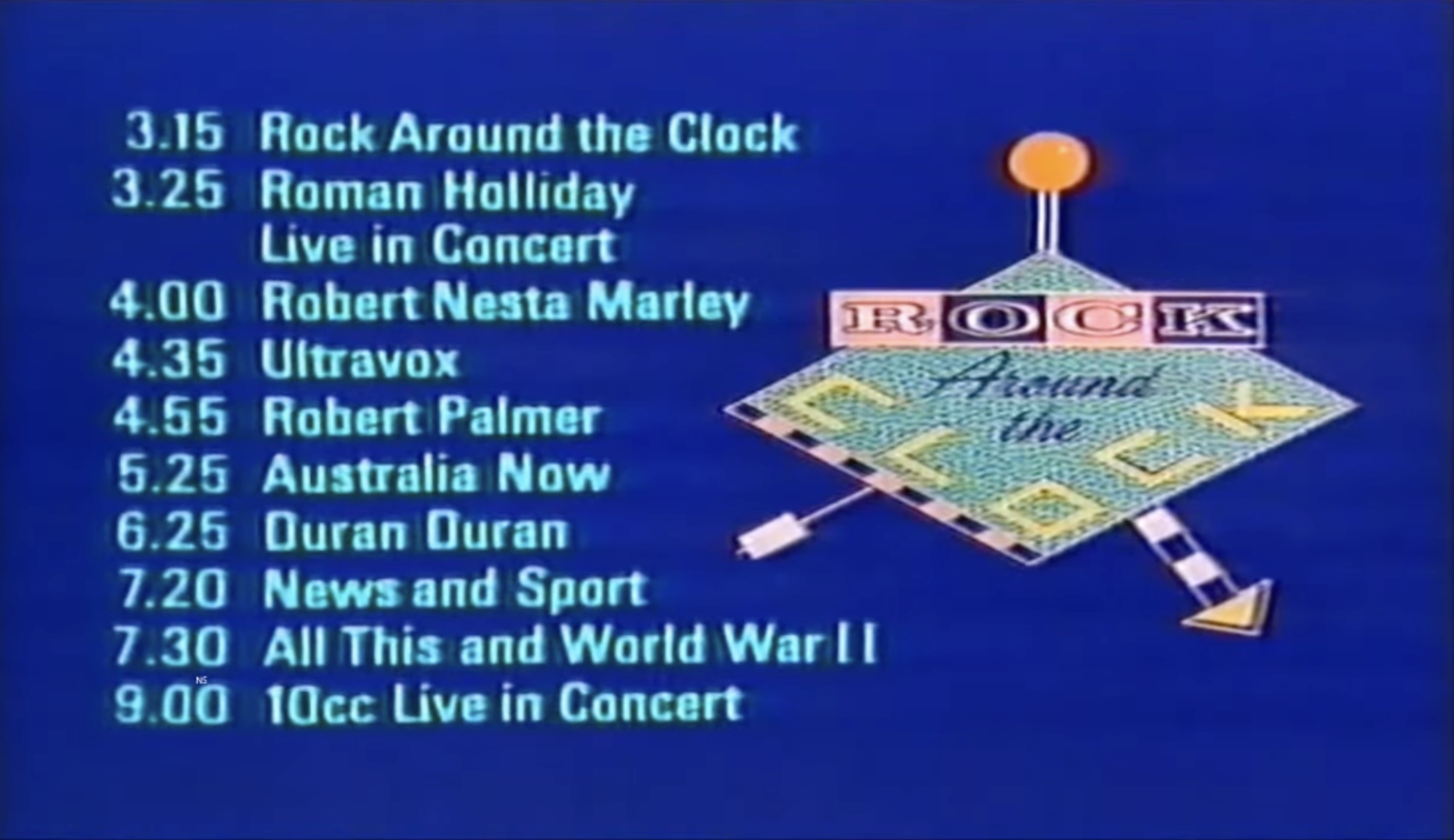

There was also the first of three all-night events, entitled Rock Around the Clock. Broadcast in 1983, 1984 and 1986, this was a cross between a telethon, and (as Radio Times described it) a rock music channel.

(Courtesy David G. Croft)

Probably quite exciting at the time, this was very much of the era, with music celebs all manning the telephone. These included Fish, Meatloaf, and Tony Butler from Big Country. Joining the regular OGWT teams of the time, was Annie Nightingale who returned for one night only for the 1983 edition, replaced in 1984 by Josephine Buchan – presumably poached from Pebble Mill at One, and Janice Long in 1986.

(Courtesy David G. Croft.)

Rock Around the Clock is great for archivists across the land. The marathon featured some interesting acts, some really quite amazing and curious set design (1984’s video line-up looked like the lovechild of Deep Thought and a Blue Peter totaliser) a healthy dose of incredulity with several presenters convinced no one was actually watching them at 3am, and some cringeworthy moments, such as an embarrassed David Hepworth reading out a request on behalf of a viewer who wanted to ask Josephine Buchan out for dinner – she said no.

Meanwhile, the format of the regular OGWT series had remained fairly consistent, with two live acts on stage, interviews, promos and some occasional features connected to the world of pop and rock. Sure, there was a bit of banter between the two hosts, but the presentational style was still very much no-thrills. Perhaps this was a measure that the show still felt comfortable with its audience, and had noted its competition, deciding that it could happily co-exist with other shows that were not interested in straying into OGWT‘s late-night territory. Indeed, Radio Times listed OGWT as the show that took its ‘own view’ of the rock scene.

However, change was on the horizon – the result of inter-departmental manoeuvrings within ‘Network Features’, new blood, new production teams, and some BBC2 controller influence.

The first manifestation of this was a momentous announcement made by Hepworth and Ellen at the beginning of the annual Pick of the Year edition of OGWT in December 1983.

I’ve always felt that Blue Peter was the leader in solemn announcements – you know, the death of beloved pets, vandalism of Italian sunken gardens – that kind of thing. However, OGWT added extra gravitas to its own big news by delivering it from the ‘Penthouse’ BBC production office.

Following one last segment of the original theme music, Hepworth revealed that the Stone Fox Chase theme music was to be no more.

The other revelation, was that the ‘Old’ and the ‘Grey’ were to be consigned to history, an indication that times were changing, and that the fizzy, flashy, modern 1980s had no place for anything ‘Old’, ‘Grey’ or vaguely mystical, such as a figure kicking stars.

Indeed, the end of Roger Ferrin’s title sequence was re-animated, at great expense (by low-budget Whistle Test standards) for what would become a one-off occasion. A new logo would be unveiled a couple of weeks later. The argument about whether the two words actually needed to be dropped would rear its head over the next few years.

It’s a classic Whistle Test moment. Slightly irreverent, and completely understated. Yet, it wasn’t just the name and the theme music that was to bite the dust. At the very end of the edition, the credits rolled over a close-up still of the ‘Starkicker’, the emblem of OGWT since the beginning, which span off into the forever, to the sounds of David Bowie’s China Girl.

If you look at the first (Old Grey) Whistle Test compared to the last (Old Grey) Whistle Test, before it changed its title, it wasn’t very radically different. It was an evolutionary situation. People didn’t really notice particularly and sometimes I suspect they would say it hadn’t changed at all. But it’s like all evolutionary things – the change is so gradual, you don’t notice it until you actually compare chunks that are distant from each other.

Mike Appleton (BBC DVD commentry)

Mike Appleton’s comment is interesting. Because OGWT ran so continuously until the early 1980s, it was unlikely that audiences would have noticed any stylistic shifts. Other long-running series, such as Doctor Who can easily be divided into eras, often determined by the vision and stylistic decision-making of the BBC producer in charge, so the changes are more obvious – particularly in hindsight.

OGWT is the opposite of that – with one ‘showrunner’ who, in effect, founded the show. But even then, there were subtle changes, notably a broadening of the type of features it included. The discussion of film and literature coincided with the arrival of Annie Nightingale, and the departure of longstanding Bob Harris. Appleton felt OGWT had a small audience, but the production team knew who that audience was and ensured the programme catered to them.

However, audiences grow up, as do tastes. So, while the early 1980s saw more frequent modifications that were mostly stylistic in nature, a changing broadcasting and cultural landscape necessitated a clear decision—either carry on as before or revamp.

A new era, accompanied by significant changes, was around the corner.

Next Time – A tale of two producers. No Longer Old, No Longer Grey – Part Two.

References and acknowledgements at the end of the final chapter.

Leave a reply to Tim Dickinson Cancel reply