A decision was made to try Whistle Test in the early evening, in an attempt to catch a young audience.

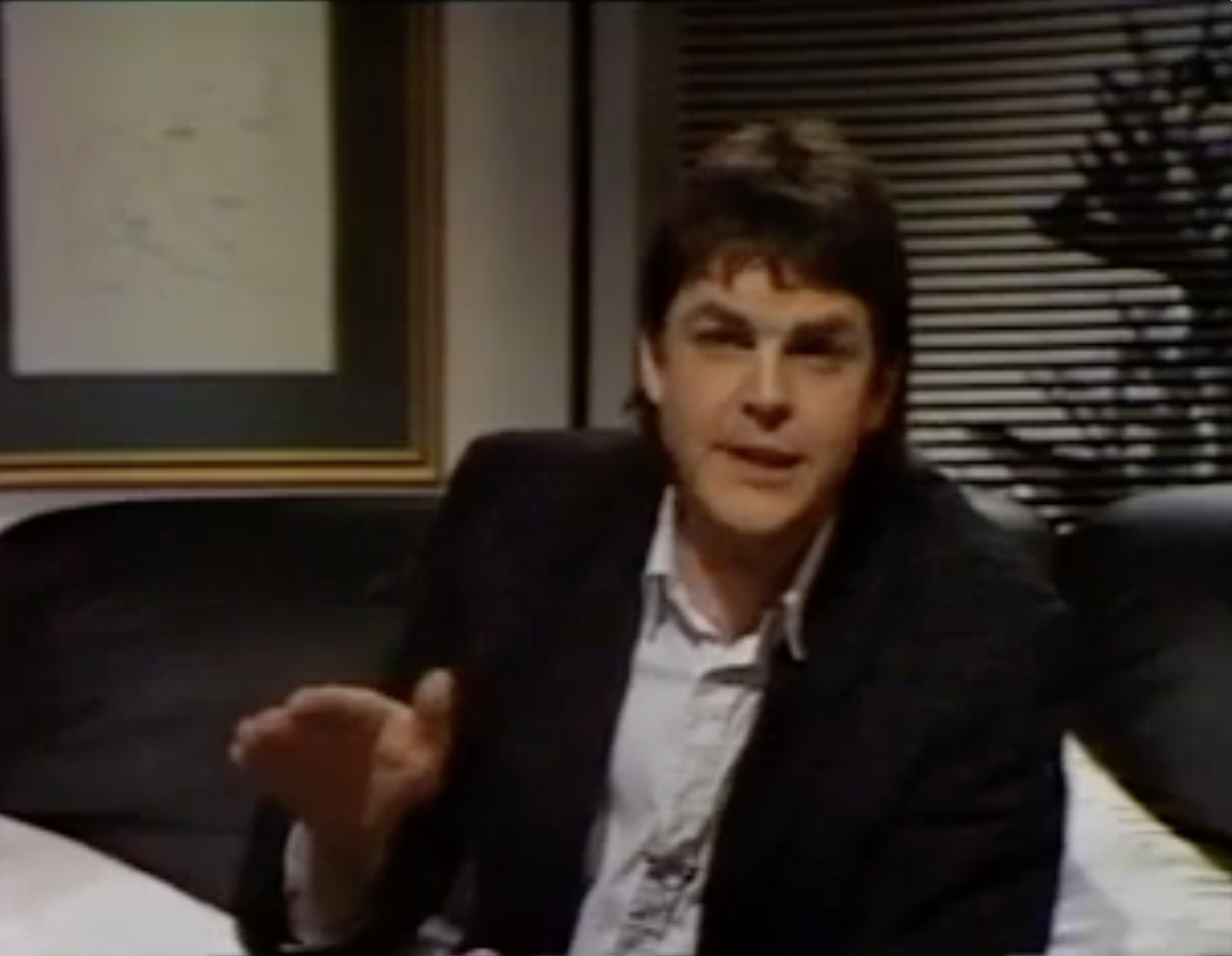

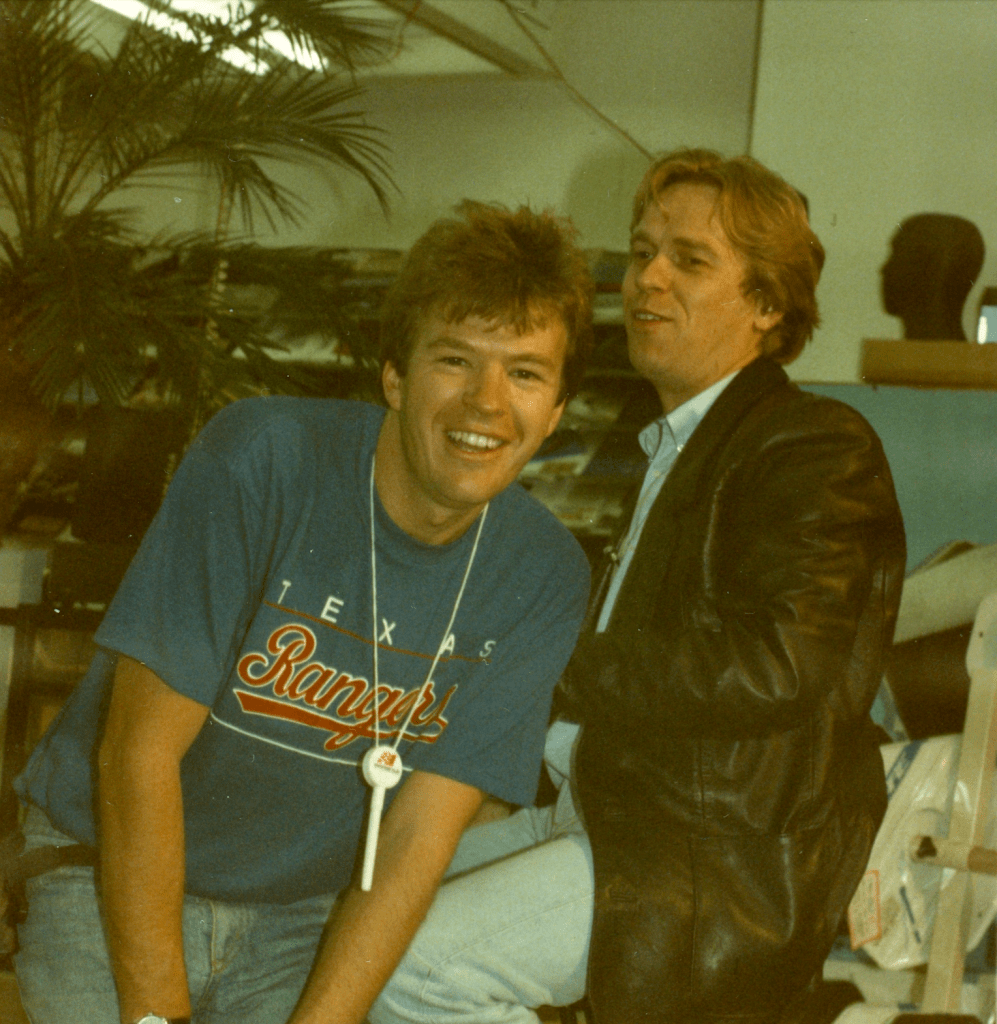

John Burrowes.

By 1984, The Tube was firmly established as a successful new approach to music television in the UK, and the pressure on the BBC was felt at a senior level. Feeling the need to bring Whistle Test up to date, BBC2 controller Graeme MacDonald made three significant decisions. Firstly, the show would air during an earlier ‘prime time’ evening slot at 7.30pm, in the hope of grabbing new audiences. Secondly, the series would be given a modest (by its own standards) budgetary increase. Thirdly, the series would be transmitted live.

These were significant decisions, and as we will discover, they would have a profound impact on the longevity of the show.

So, what did this revamp look like, and what did it do?

The bands were going to be different, and of course, we had this thing lurking in the distance called The Tube. No longer was Whistle Test on a Tuesday night at 11 o’clock when everybody gone to bed, and you were sat with Whispering Bob. We now needed to be live, and a bit more in people’s faces, and a bit brasher.

David G. Croft

The publicity machine (for once, there actually was one) was cranked up, and lines like “No Longer Old and Grey” and “Trans-generational appeal” were fed to the press by the BBC.

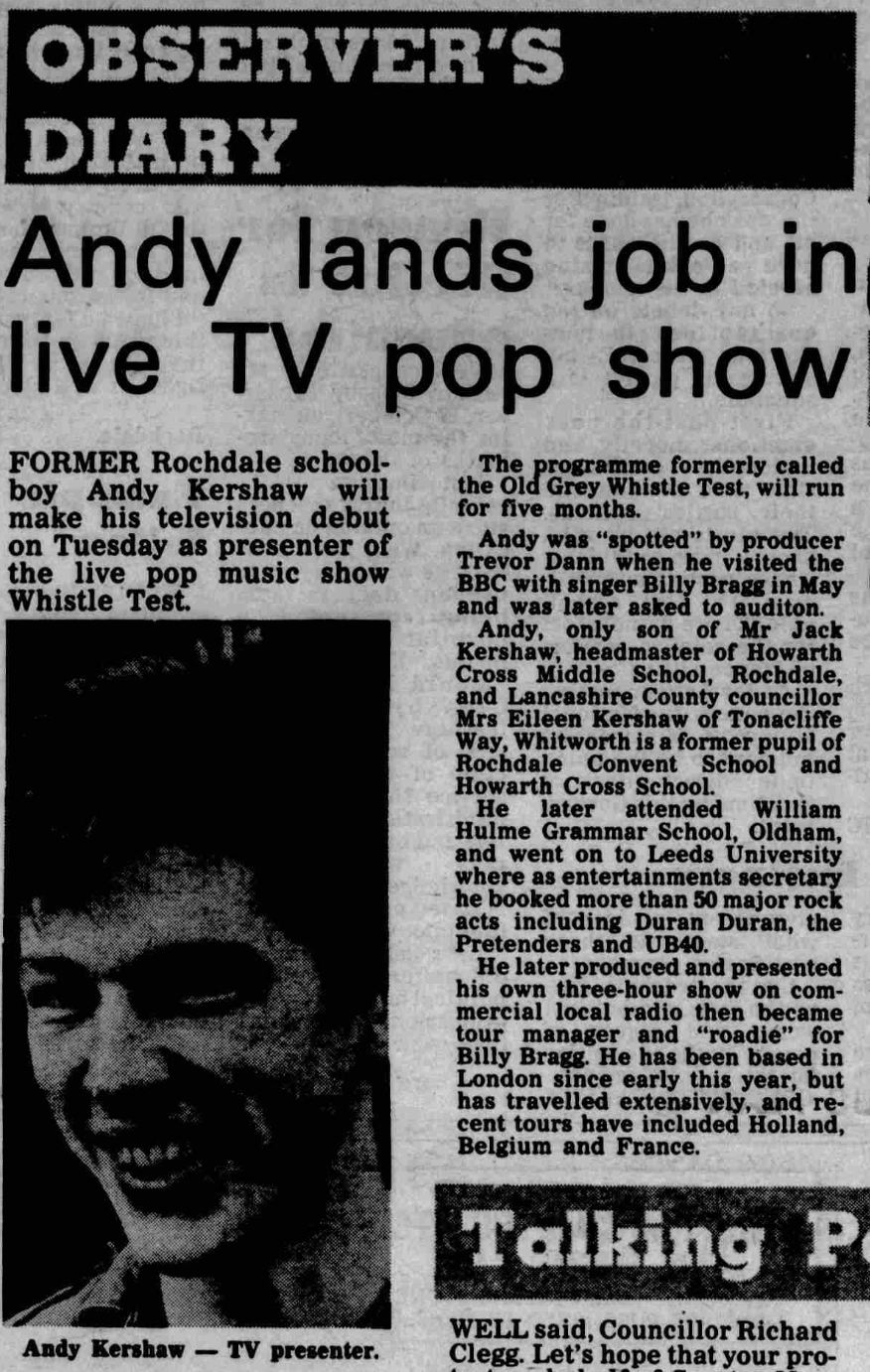

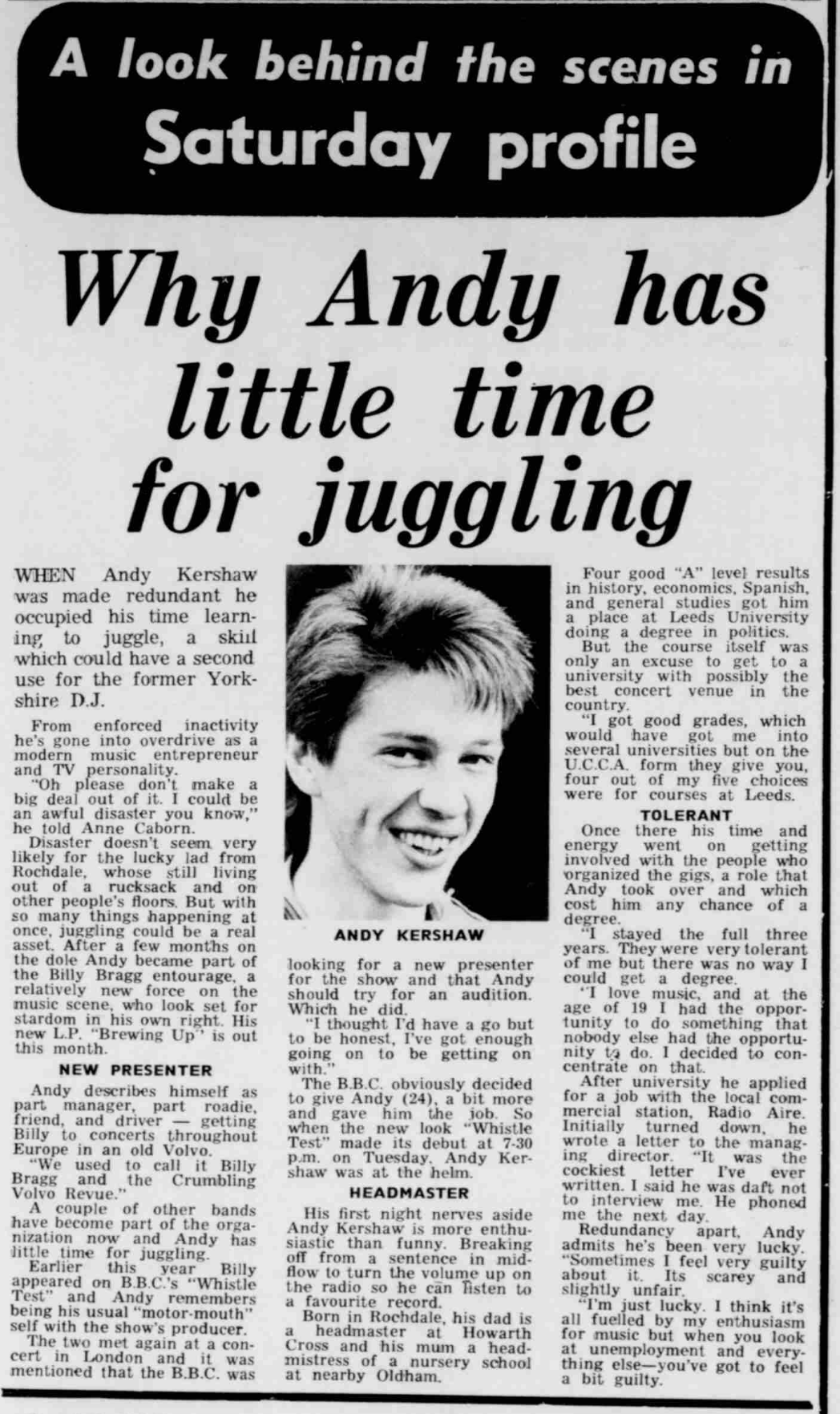

The new live series introduced fresh faces in front of the camera. At the same time, Jon Lewin’s article about the previous series in One Two Testing magazine was written (see part 2 of this story), Billy Bragg was booked to play Whistle Test, and brought his roadie with him. His name was Andy Kershaw.

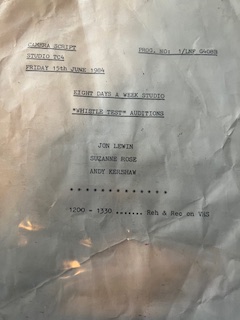

In mid-June, producer Trevor Dann invited Kershaw to audition for the role of Whistle Test presenter, overcoming stiff competition from Jon Lewin himself.

I had met Andy Kershaw because I was doing a local radio show and he brought Billy Bragg in. We went down to the pub together and I said “Well, what about this this monstrous guy from Rochdale?” So, we got him into to do an audition, and he was fantastic.

You wouldn’t do it now because you’d say “Well, there’s no women” but then those kind of things were not on the agenda. They should have been, but they weren’t.

Trevor Dann

In his autobiography, No Off Switch, Kershaw recalls the outcome of the audition, with Dann considering the Rochdale lad to be someone who could give Whistle Test something new. The music journalist, David Sinclair, played the part of a rock star, and Kershaw was required to interview him. Sinclair was wearing an old, battered, red leather jacket.

And you got him to talk about that rather than himself. It was when you said to David, “I bet that jacket could tell a tale or two” that I yelled in the control room, “That’s him! Sign him up!”

Andy Kershaw, quoting Trevor Dann (No Off Switch)

Another presenter was waiting in the wings – Richard Skinner. Dann first encountered Skinner when he was a Radio 1 producer in 1979. The Winter 1984 Whistle Test series acted as an audition of sorts when he was featured on film interviewing The Style Council. In fact, Skinner had a significant presenting pedigree, from being a continuity announcer for Thames Television, to fronting Top of the Pops.

I tried him (Skinner) out on a couple of things and he was a very good interviewer, so I used him. Richard came from that background, and was, by then, doing Radio One early evenings for a while.

He could listen to lots of different things in his ears and keep smiling, and he had a nice manner about him. He was great for something like the Video Vote because he was a bit more together. He struck me as more consumate.

Trevor Dann

Skinner appeared to have a very specific role in the new Whistle Test. Rarely venturing away from desk-based duties, he would host interviews and be master of ceremonies for two new features – the video vote (more on this later) and the live rundown of the UK Top 30 singles charts, which had been just announced by Gallup in time for the show’s transmission. This emphasised the ‘live’ element of the new format, and also distanced itself from the OGWT of the past, which had prided itself as being an album-only show. These new features and interviews required a little more presenter input than usual, and Dann felt comfortable with having Skinner hold things together.

On Tuesday 23rd October 1984, at 7.30pm, the BBC2 logo appeared, and the continuity announcer introduced Whistle Test, cutting to a very new dynamic for the series – an up-to-date title sequence and theme tune.

Mike (Appleton) was not very happy about losing the Starkicker.

Trevor Dann

The discussions about the opening titles were endless. If you’re in a situation where you’ve created a brand image – the Starkicker – which is so successful, and then you say we’re not going to use that anymore. It’s like “Wow, how do we replace something as iconic as that?”

It was a terrible challenge, but the Starkicker felt very Seventies and needed to be retired. I know there were endless chats about what should it be.

David G. Croft

The new sequence was created by a young BBC graphic designer, Martin Foster. Whistle Test was his big break – a milestone in a journey from a Royal Society of Art bursary to holiday relief cover in the BBC Graphic Design Department. This unit was a team of 10 designers, led by Oliver Elmes (think The Good Life and the 1987 Doctor Who title sequence.) This resulted in a permanent job as an Assistant Designer under Graham McCallum, who, coincidentally, was responsible for the title sequence for Riverside.

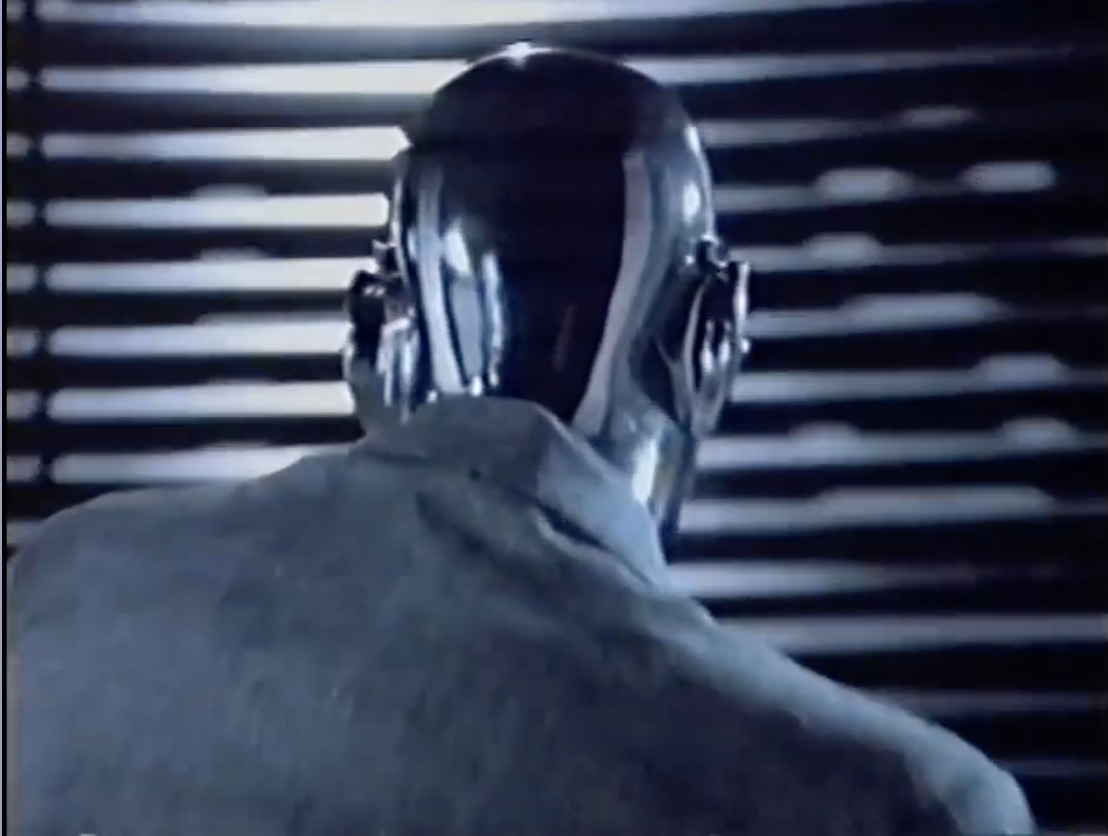

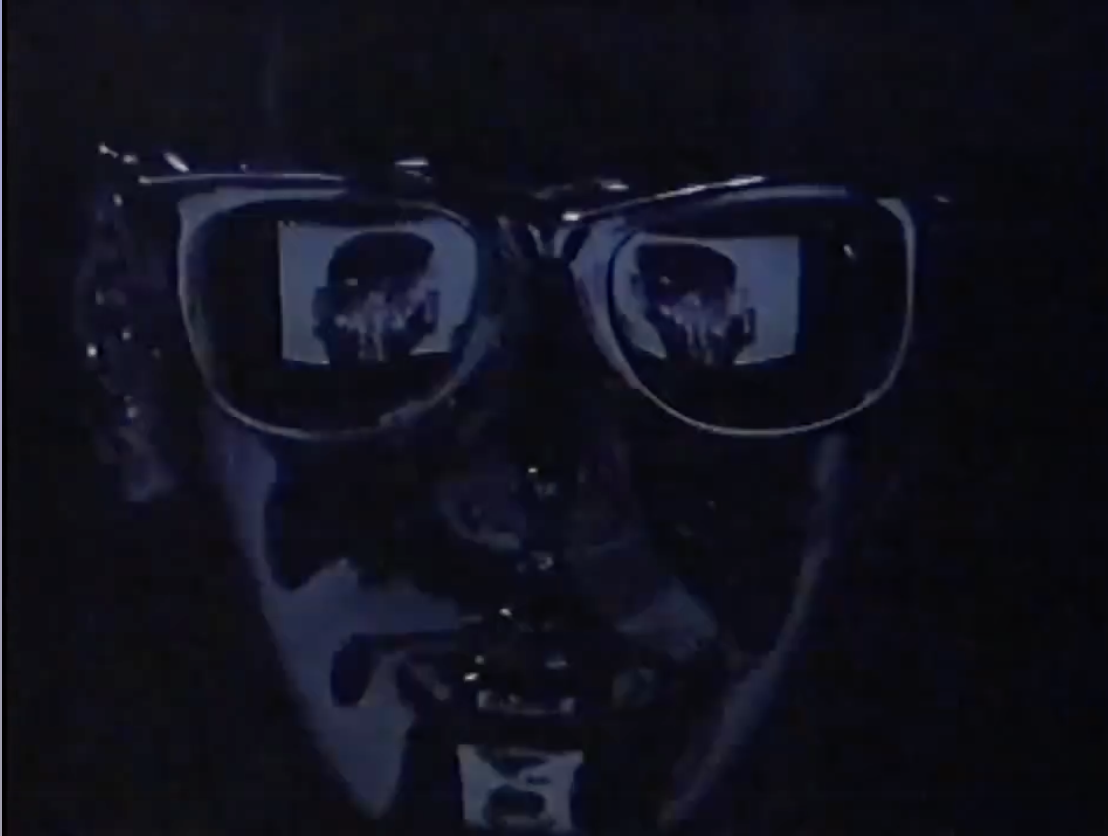

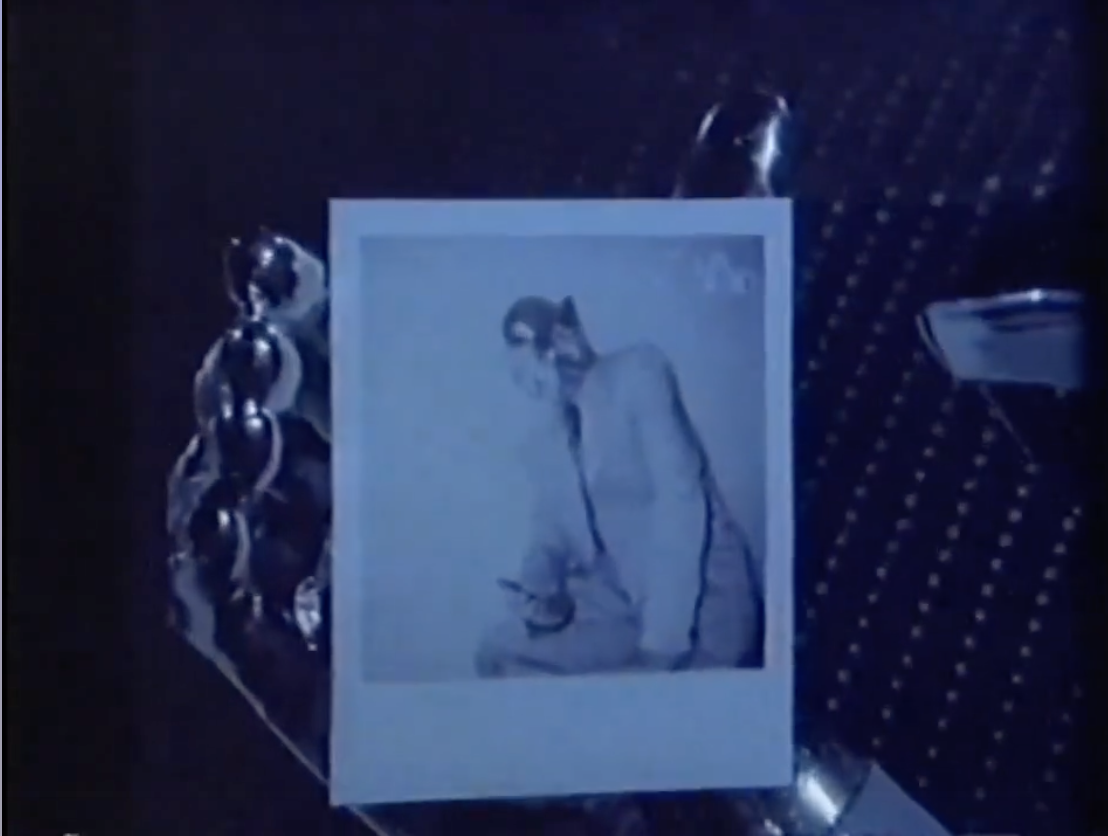

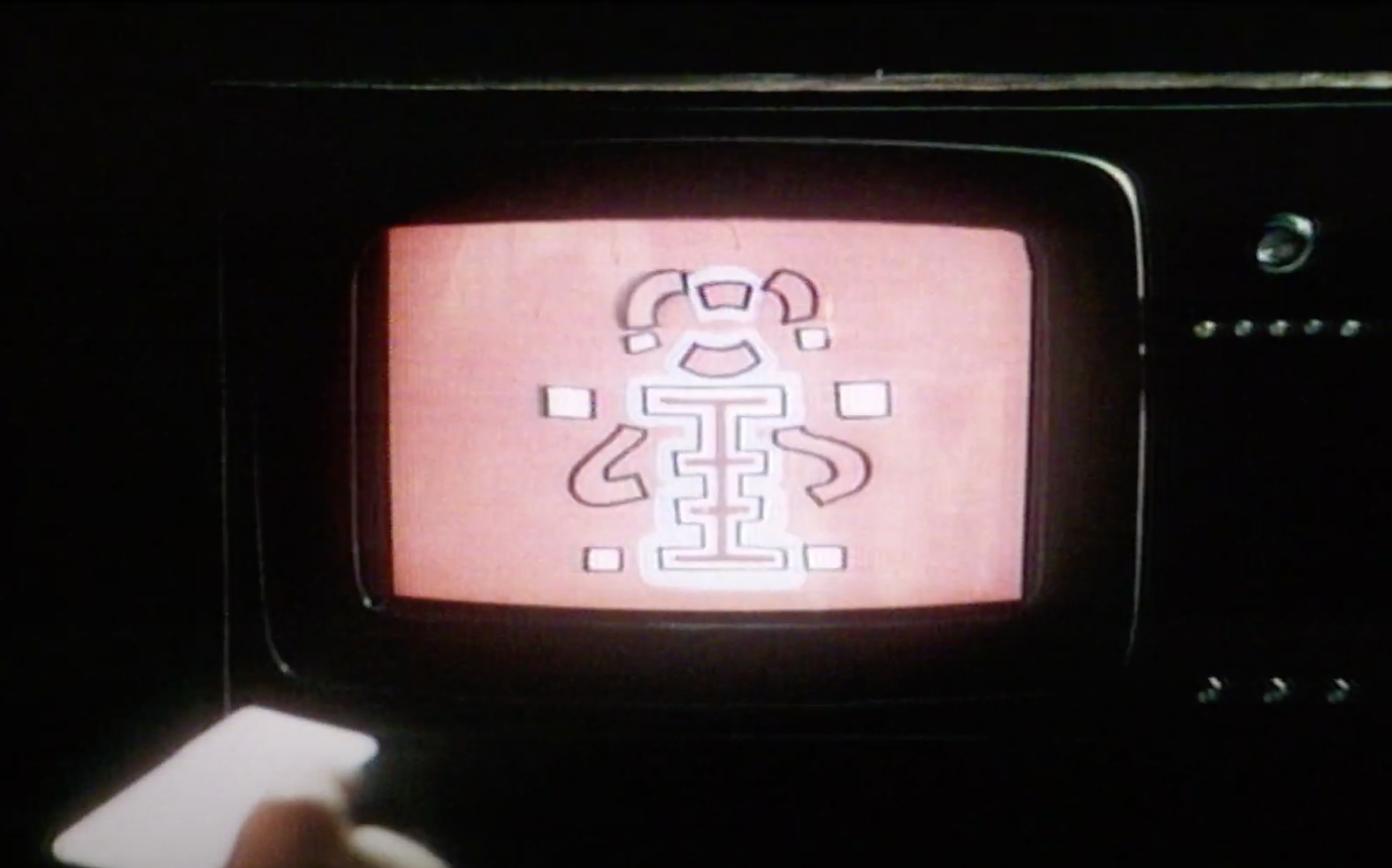

Within hours I presented my storyboard. A shop dummy in a smart suit watching a TV set. We would have some lasers flashing about. I raced around getting all that together – bought a dummy, had the hands and head chromed, got a suit and arranged the shoot at Damson Studios. The cameraman was Douglas Adamson.

Martin Foster (quoted in Graphic Design for Television, 1993)

Having worked on everything from Gainsborough Studios, to the most recent ‘flying discs’ titles for Top of the Pops, the experience of Douglas Adamson will have been highly beneficial to Foster.

Many people, including Foster himself, assumed that Dave Stewart from Eurythmics provided the opening music. Given that the theme and titles were created separately, we can be a bit forgiving.

In fact, the musician in question was the keyboardist Dave Stewart, who worked with a number of progressive groups and was noted for his long-standing collaboration with singer Barbara Gaskin.

I was invited to write a new OGWT theme by Trevor Dann, who I knew originally as a radio presenter – I remember he liked our single ‘Leipzig’ a lot and played it on his radio show. I was given no brief and there was no collaboration with the designer of the title sequence, though I would have happily written to picture if that had been the job. I think Trevor just told me how long it needed to be and left me to my own devices.

Dave Stewart

Dann might have made the phone call, but asserts that it was not his decision to commission Stewart. Either way, it would appear that the new introduction to the show was the result of a lot of debate and discussion, perhaps spilling into the eleventh hour, resulting in a quick turnaround and swift deadline.

It was spontaneous piece of composition with nothing planned in advance. I programmed a drum track with a similar swing feel to the original theme (not a conscious decision, it just came out that way), improvised a bass line using a slap bass keyboard sound, and threw in some samples. It didn’t take long.

Dave Stewart

Based on Stewart’s recollection, it seems plausible to assume that the music was written first, giving Martin Foster a clearer hand in timing the filmed footage. Although it might also suggest why Foster was up against a tight turnaround.

I had only three weeks – such a rush. The series had been offered to other designers and they had all managed to argue that there was insufficient time! I was an assistant and the brief was sitting on a desk when I rushed in and said “I want to do this”. It was my life’s ambition.

Martin Foster (quoted in Graphic Design for Television, 1993)

It would appear that a number of the production team were generally happy with the final visual outcome, although there were some dissenting voices about the wider decision to drop the ingredients that had made OGWT so distinctive.

I think we all liked the new titles. It was very much a response to changing times. It wasn’t the 70s anymore, it was the 80s – the style was different.

David G. Croft

It just invited ridicule to say “no longer old, no longer old grey”. You know the original logo – the man kicking the star, and the original tune – Area Code 615, was so strong, they should have just left it alone. Everybody knew Whistle Test from those two things.

Andy Kershaw

Changing the name and vibing up the titles or whatever, it doesn’t make any difference at all. In the end you know, because things go out of fashion then they come back in again.

David Hepworth

I did think, they’ll never better the Starkicker and Stone Fox Chase. I have a vague recollection that perhaps the mannequin supposed to be the Starkicker coming to Earth? I quite liked the Starkicker/mannequin as part of the set.

Karen Rosie

Meanwhile, the new theme polarised opinion.

It just kind of said “Hey, that’s not the music we play”.

Trevor Dann

Later someone told me Andy Kershaw absolutely hated it, which I thought was funny – at least it made an impression on someone!

Dave Stewart

It’s easy to knock a reinvention or an attempt at replacing something so established and popular. However, taking out the separate argument about retaining the older and greyer elements, I think this particular collision of sound and vision is largely effective in setting out the Whistle Test stall. A quick comparison with The Tube is useful. All of the ingredients of Channel 4’s raucous, high-octane, wild child are recognised in every title and theme used during its five-year lifespan. They are all fast, punchy, and confrontational – they tell the audience they are in for a roller coaster ride.

In perhaps the most famous Tube sequence (designed by Annabel Jankel and Rocky Morton of Cucumber Studios), the logo bursts out of the television set like a space shuttle, startling a family of half-dead, life-size waxworks.

But the approach to Whistle Test is different. It is about characterisation and symbolism, rather than in-yer-face tone and energy. The Foster/Stewart collaboration is a bold refresh, which places style firmly at the centre of the concept – perhaps a novelty for Whistle Test. Of course, there is the subjective nature of style, and how quickly something can go out of fashion; however, a new live show needs a new approach in terms of branding. If there is a drive to gain a fresh audience, then a new concept is important.

The plundering of cultural and design references, from video art, fashion, and the use of new technologies, is perhaps the ultimate expression of the ‘New Live’ Whistle Test. Just as the original sequence dates the end of the ‘counterculture’ era, this new version echoes the sensibilities of the 1980s, where music meets commerce meets style in a similar way to the recent TV commercials for Maxell tapes, featuring Peter Murphy of Bauhaus, who menaces the viewer with side-eyed stares sharp fashions, neon lights, lasers, living room setting, and pinpoint lighting.

Yet, the opening titles also manage to reference the identity and traditions of the show. The chromed mannequin acts as a figurehead in the same way that the ‘Starkicker’ did. Perhaps they are the same thing? There is even a nod to the original sequence between the figure and a flash of light. Alongside the theme music, which is similar, yet different to Stone Fox Chase, the sequence echoes the series’ past, and points at ‘the now’.

Unlike The Tube, this is not about convincing anyone that Whistle Test is an explosive, life-changing show. In fact, it shuns any reference to audience impact, in favour of recognising its own authority as the ‘knowledgeable’ music show. Roger Ferrin’s memorable and symbolic visuals were a tough act to follow, but this new sequence is a bold, worthy update.

In the studio, a new performance area was introduced – a design that represents more than is initially apparent. The distinctive cyclorama that screamed modern art was replaced by a plain black backdrop, framing a contemporary rostrum with white railings and rows of stage lighting. This suggested a concert setting – a way of emphasising that the show was now live.

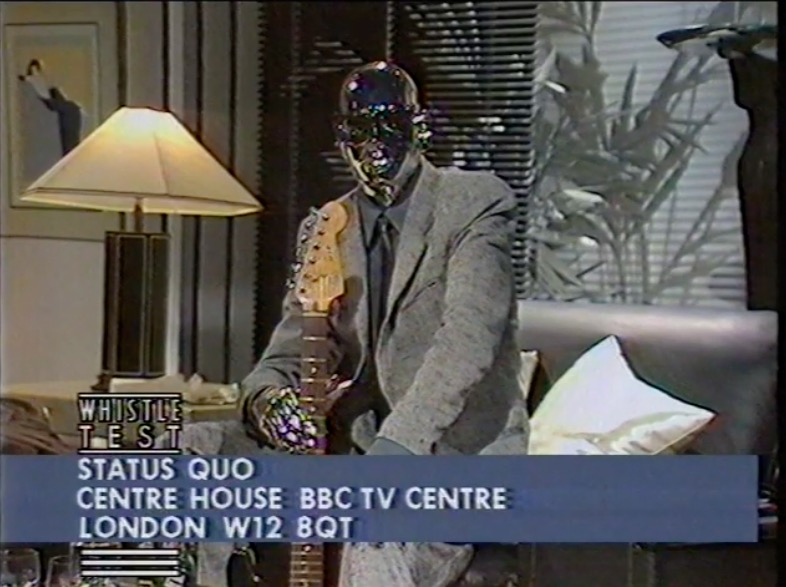

Hidden in plain sight, at the rear of the stage, was the chromed mannequin seen in the title sequence. This new figurehead would often be seen in the studio, smoking, drinking, holding a guitar, and adopting several (obviously) fixed poses. Again, this suggests the desire to hammer home a strong visual identity.

The familiar face of David Hepworth, perhaps based on the fact that he had been around for the longest, was chosen as the presenter to launch the proceedings.

HEPWORTH: This is a new series of Whistle Test. New day, new time, new length, and believe it or not, it’s live.

Perhaps, it was hard to believe, for the presenters at least. Yet, the audience might not have known any different. Whistle Test had been pre-recorded for a number of years, but there was little in the presentation that suggested it was anything other than live.

Following his opening link, Hepworth walks to what initially might have been familiar to viewers of the previous series, as an office with its grey backdrop, desk, and Venetian blinds. However, on a second glance, this was an upgrade from the previous series. This was ‘The Comfy Area’ – both an economical and somewhat knowing title.

It was called ‘The Comfy Area’ because we were being ironic. It’s like “Hey, this is not very Rock and Roll. So we’ll take the piss out of it by calling it The Comfy Area.”

When you’re making a studio show where there’s several different areas. The directors and producers will always name those areas, so that it is quick. All the areas would have had a name because then it becomes your shorthand when you write the script, “David standing in front of Comfy Area“. Floor managers would know “Right David, you’re over there“.

David G. Croft

The space itself was a mishmash of different styles, from Art Deco to 1980s chic. Stock BBC wall lamps, palm trees, blinds, and marbled table lights surrounded a swanky new desk and chrome leather sofas, where links would be presented and interviews conducted. The sharply attired mannequin appeared at home.

If you will indulge me, I think it is time to stick on the gallery theme from ‘Vision On’ and take a look at the collection.

A contemporary painting by Nicholas Williams entitled ‘The Garden‘.

A lithograph by Oliffe Richmond called ‘Standing Group‘ circa 1966.

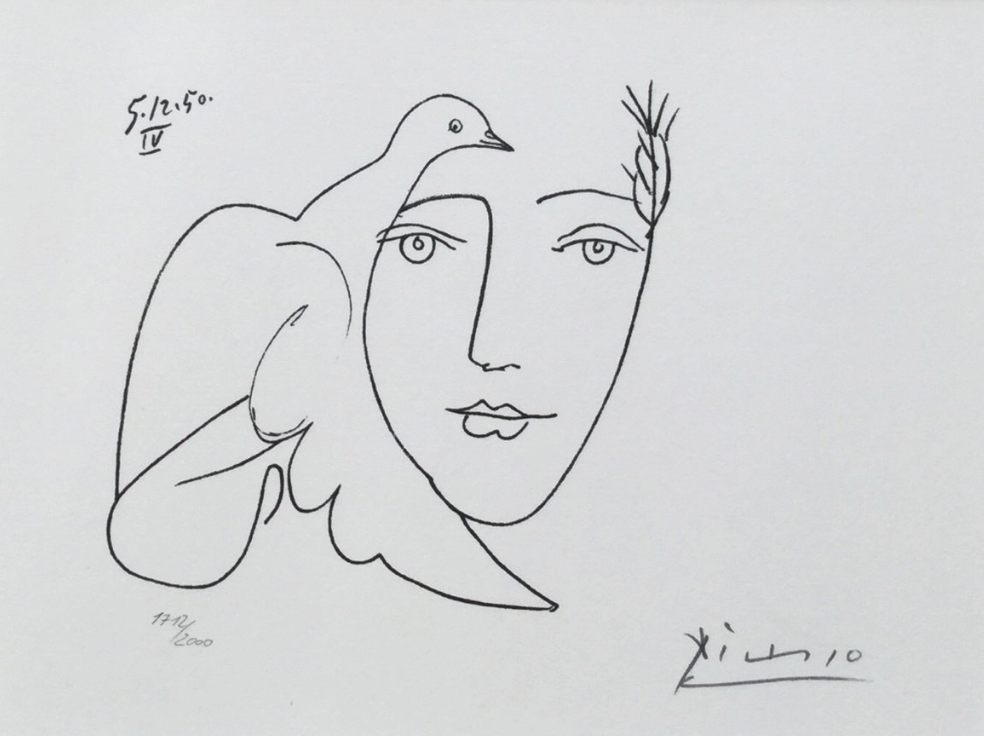

A print from a collection of works by Pablo Picasso – Visage de la paix (The Face of Peace) from 1951.

Also prominent was ‘Garcon – The Waiter’ from 1984. This was a black/silver painted fibreglass and chromed metal platter, by artist Lindsay Balkwill (Lindsey B). One sold at Bonhams a few years ago for £2500.

Whistle Test had never known such luxury, nor been so contemporary in its style choices!

The Comfy Area was clearly a space designed to give four presenters a bit more elbow room.

The set would always have to be something within budget that could get in and out of a studio very quickly, to make space available for other shows. We wouldn’t be priority in terms of time and budget.

The Tube and other music, fashion, and culture shows would have been an influence.

Karen Rosie

The choice of live in-the-studio band for that first edition was ‘Violent Femmes’. It made sense. They were new, mixed genres (folk/punk/country), and had a bit of attitude that might have appealed to a younger audience. They were also American and maintained a sense of musicianship that was a key part of the Whistle Test DNA.

For Kershaw, being thrown into live television was terrifying.

Andy Kershaw (quoted in Old Grey Whistle Test – Live for one night only).

The moment came, and I saw that red light come on over the camera, which meant that the camera was live and pointing at me, and we were going out… I think I’d reached that point where complete and utter fear fades into the serenity of fatalism.

As that first episode continued, it was easy to see how eclecticism was always a distinguishing feature of Whistle Test. So, it is only right that another section of the audience was catered for with filmed performances by Van Halen and AC/DC from the Monsters of Rock festival in Donnington.

In fact, that Monsters of Rock report was not only notable for it being Andy Kershaw’s first incursion into Whistle Test territory but also due to its sheer size. Running to almost 25 minutes, it occupied nearly half the timeslot of that first edition.

Watching that first filmed insert back, it’s interesting to see quite what a set-piece the feature is, with a fly-on-the-wall feel, enhanced by shots of the crowd and candid interviews. Kershaw is positioned as the curious outsider, seeking to discover the allure of hard rock among the festival goers.

He just about makes it out alive.

Consequently, delivering my very first words to a television camera, at the Castle Donington Monsters of Rock Festival, in August 1984, I was encouraged to get my tits out as two-litre plastic cider bottles, refilled amusingly with hot piss, were hurled in my direction, spinning away, off target, like liquid Catherine wheels to detonate, amid much cheering among fellow connoisseurs of these time-honoured merry rituals.

Andy Kershaw (No Off Switch)

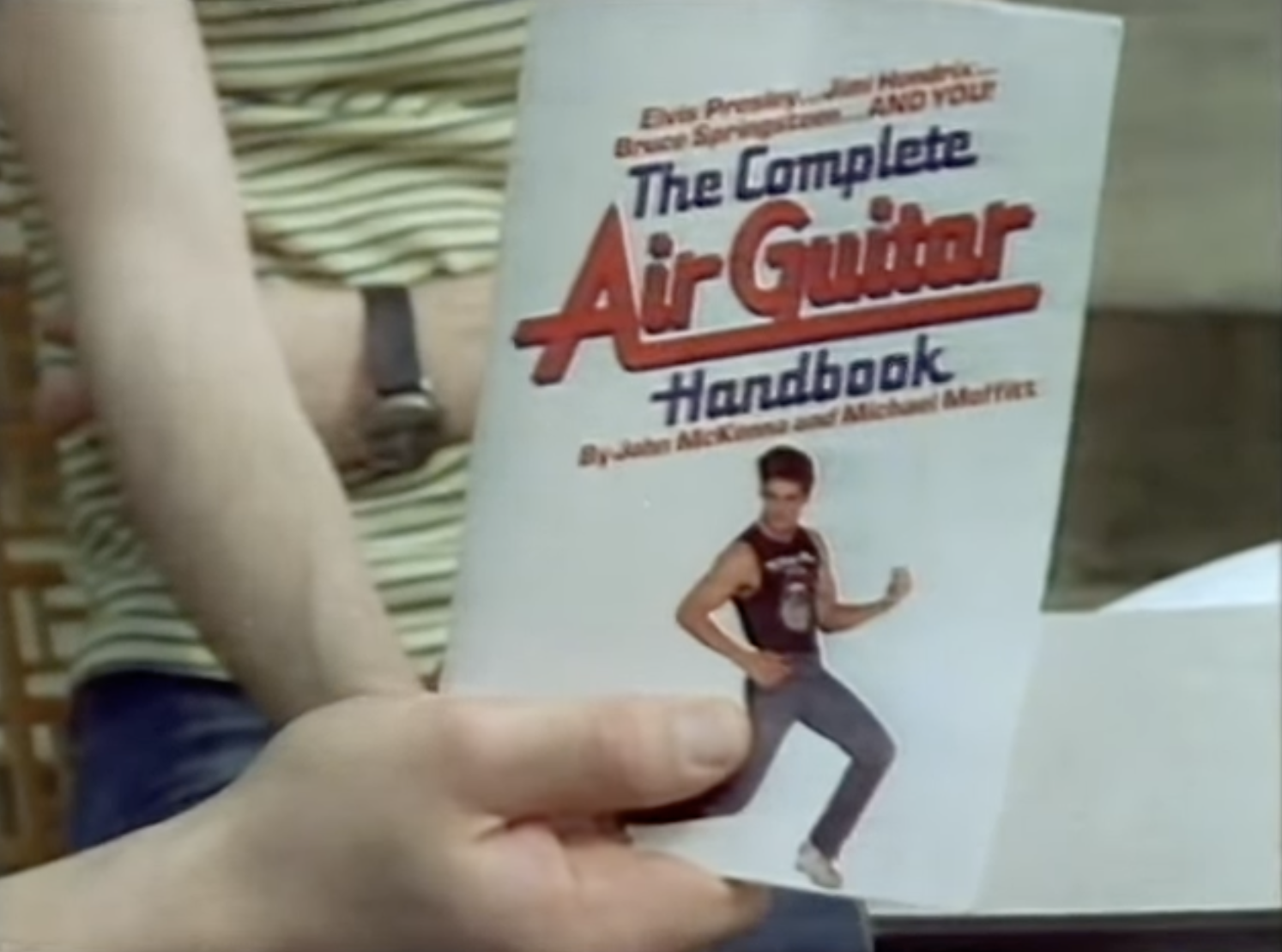

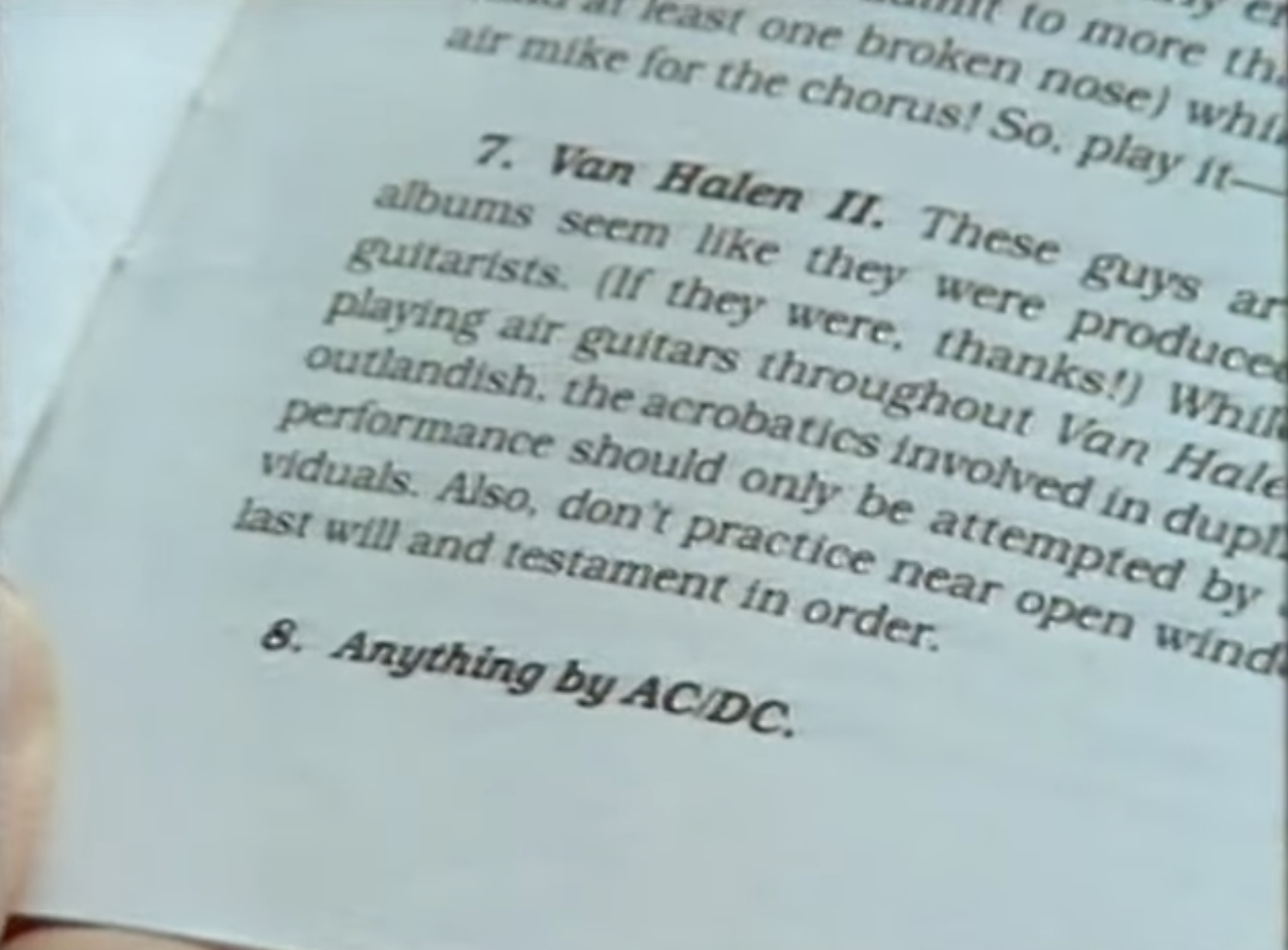

Whistle Test presenters have never been backwards in coming forward. And that is true for Kershaw, too. The report plays up to familiar Spinal Tap tropes, allowing a playful take on the subject matter, occasionally bringing out something new. For example, during an interview with Angus Young and Brian Johnson of AC/DC, Kershaw brings out a book – The Complete Air Guitar Handbook, which includes the eight best air guitar albums. Kershaw excitedly reveals the number 10 entry – “Anything by AC/DC.”

KERSHAW: Are you appalled that you are lower in the air guitar stakes than Van Halen?

It works both ways. In the comfort of the ‘Beaver Suite’ in a nearby hotel, Alex Van Halen is handed the same tome, allowing David Lee Roth to return the cheek, offering Kershaw a blank book.

DAVID LEE ROTH: And here we have a simplified version of ‘The Joy of Sex’ for you.

Kershaw suggests that hard rock and heavy metal all sound the same. Angus Young, brushes this off with a degree of weary humour.

ANGUS YOUNG: “People think we play the same thing over 11 albums, when in fact, it’s 12.”

The shopping list of asides are ticked off one by one. Then, for a brief moment, Van Halen is wonderfully earnest

EDDIE VAN HELEN: “A lot of the time we are asked ‘What do you think of the resurgence of Heavy Metal, and the leather-clad people, and whatever. We’re just making music. We’ve been doing the same thing for about 11 years, the way the band is. And…it hasn’t changed. It’s something that instills a kind of…it makes people joyous. That’s about the best way I can say it. As long as they have a good time, we have a good time, great. And we get paid a lot.”

But it doesn’t take long to return to the default setting. When asked about the idea that everyone is really nice behind the on-stage persona, David Lee Roth, offers a response to rival Spinal Tap

DAVID LEE ROTH “I’m a very kind of family-oriented guy. I’ve personally started three or four since January.”

It’s hard to imagine David Hepworth or Mark Ellen delivering the same I-can-get-away-with-it style that Kershaw brings to the Monsters of Rock report. Their style and strengths were elsewhere.

For my money, Hepworth appeared to be the more authoritative voice. With a tilt of the head, he came across as more aloof and unflappable, able to offer a dry opinion and an ability to reign in his excitement or disapproval, except if the subject in question was Bruce Springsteen.

(Courtesy of David G. Croft)

Mike Appleton always said that the programme should be journalist-led. If you’re going to present music on the telly, you’ve got to be a bit of a cheerleader. We weren’t like that at all, because we’re journalists. We were…(noncommittal) “well, they’re alright”, or we’d go (excitedly) “No, this is great!!!” And that’s what journalists do. They’re snobs. They’re opinionated.

I introduced REM. And let me tell you, standing in front of a band, introducing them when they can hear you, is the worst thing in the world. You have to compose something to say about them, which is not what they say on their bio. Because their bio always says “World beating four-piece from Athens, Georgia, their new album is the greatest thing they’ve ever done. The greatest thing anybody’s ever done.”

You can’t say that.

David Hepworth (quoted on Old Grey Whistle Test – Live For One Night Only)

Mark Ellen offered a perfect foil to Hepworth; a knowledgeable, jovial, animated, and optimistic character, whose delight in introducing particular acts, such as Robyn Hitchcock and the Egyptians, was barely disguisable. He also gave the volatile or fickle musician a chance to highlight their best qualities. Although I imagine he wasn’t thinking this when stuck up a mountain with a difficult Jimmy Page and Roy Harper making sheep noises. (Check out Ellen’s memoirs for more on this toe-curling story.)

Richard Skinner added solidity and confidence to the proceedings. He was often able to take things in his stride, such as unruly rock stars. Take this amusing exchange with Johnny Rotten.

SKINNER: Johnny, you there John? You were meant to be here not there, weren’t you? What’s happened?

ROTTEN: Well I couldn’t get a flight, and I didn’t want to anyway, and I’ve got much better things to do.

SKINNER: (Laughing) Well cheers then. Okay well while you’re on the phone we might as well talk to you anyway.

And how did Kershaw come across in his first series? Well, that would depend on the music he was presenting. Sometimes he might link a 1980s power pop act through gritted teeth and a fixed stare to the camera, or freeze in his excitement for a band like The Long Ryders (more on this in the next chapter.)

But perhaps his most famous link was in his boyish enthusiasm – with clenched fists – for The Ramones:

KERSHAW: So, turn up the telly, throw open the windows, death to timid pop, here are The Ramones!

It was a bit of a shock, not just to find myself a presenter of the programme in the autumn of 1984, but to discover on my arrival just what a shoestring operation the Whistle Test was. In fact, the budget for the programme was so meagre, shoestrings would have been a luxury. We had no money for autocue, the presenters’ safety net. We wrote out the bones of our links in marker pen on huge sheets of white card. When I was doing a live introduction, Mark Ellen would stand next to the camera holding my prompt. When it was Mark’s turn to speak to the nation, I would do the same for him.

Andy Kershaw, quoted in The Old Grey Whistle Test Quiz Book.

As a viewer, I feel that this was a well-balanced line-up. While Skinner, Hepworth and Ellen brought their own personalities and experience to the mix, Kershaw was the first presenter who brought an ‘edge’ to proceedings. Sure, Bob Harris famously derided Roxy Music, and The New York Dolls, and it is true that Nightingale, Hepworth and Ellen, were not shy in asking tougher questions. But Kershaw’s youth, musical tastes, and principles lent an air of danger. This sometimes led to an occasionally prickly encounter, including the pressing of Ian Gillan on how much rock stars are paid – an interview that had minor consequences, as we will discover later on.

Trevor deserves credit for discovering Andy who added a new, slightly abrasive side to the team.

A case in point – a bright young production trainee on attachment came to me with an idea for a filmed item about the thriving Scottish band scene. I gave him the go-ahead with Andy as reporter. I had a plaintive call from the highlands complaining that Andy was being impossible to work with and was refusing to accept direction. The slimmed down end result was a filmed interview with Jimmy Somerville. The production trainee, is now a senior reporter with BBC News – maybe they weren’t meant to work together.

John Burrowes

By the end of that first edition, it was clear to see that each presenter brought their own style to the proceedings, and, content-wise, there was something for everyone, which can sometimes be both a blessing and a curse.

The all-new Whistle Test had launched successfully, attracting strong viewing figures and some begrudingly good write-ups. The tabloids and the odd broadsheet focused largely on the new recruits – Kershaw and Skinner. It even muted overt criticism from the music press for a while. If that was a measure of its success at the time, then so be it.

As noted in this article, Whistle Test faced the challenge of simultaneously recognising and distancing itself from its ‘Old’ and ‘Grey’ past, in the light of new – and very stiff – competition. On one hand, the show had built a substantial archive that could be plundered cost-effectively for a segment every week, not only appeasing a portion of its audience but also setting its stall as a more serious and authoritative show than The Tube. Yet its longevity, not to mention those two words, continued to haunt the programme. The result was that the Whistle Test tried to prove that it could move with the times and remain relevant in the face of criticism in some portions of the rock press.

Andy I were dragged in to see the producer after we did the relaunch. We used to refer to it as the ‘Old Grey’ and actually it had changed its name to the Whistle Test, which was hilarious at the time.

Mark Ellen (BBC DVD commentry)

There was always this struggle around Whistle Test wasn’t there? Everybody desperately sort of wanted the NME to be nice to it and they were never going to do that. You know, there’s just no point. It was a pointless thing.

David Hepworth (BBC DVD commentry)

The new and improved Whistle Test seemed to be flying, but the press still didn’t approve. The Tube was sexy and hip. We were clunky and dull.

Mark Ellen (from Rock Stars Stole My Life!)

As you probably have gathered, the broader music press wasn’t well disposed to Whistle Test by this point. Interestingly, a 1978 interview with Mike Appleton observed that it was only in the first few years of the show that there was any degree of positivity. A quick glance at the reader’s letters across different publications – from Record Mirror to Smash Hits – reveals that Bob Harris was accused of fronting snooze, and Annie Nightingale was dull. Hepworth and Ellen were described in Smash Hits as “two geezers waffling on for about a week and a half in wobbly chairs while Bruce Springsteen’s brother’s postman plays a really long solo.“

The performers fared little better. Debbie Harry – “Her ears…” The Europeans – “the worst“

There’s a hint of tongue-in-cheek with this character assassination of Whistle Test (Smash Hits was the stomping ground of Hepworth and Ellen). Still, it adds a degree of context to those final years — it was only those within the Whistle Test unit who could fly the flag for the series. The press continued their love-in with The Tube and all that came out of the Tyne-Tees studio in Newcastle.

I wouldn’t want to ever criticize The Tube. Some of the films that Geoff Wonfor did were marvelous. But some of it was all a bit juvenile for me, especially in the studio. But then it wasn’t meant for me – by then I’m in my 30s. It’s being aimed at a teenage audience who thinks that Whistle Test is stuffy. Well, fair enough, we were.

All the time that I was working with media brands, the rule was you never get anywhere if you try and be like the opposition. What you need to do is strengthen your strengths, not copy their strengths.

Trevor Dann

The supposed competition between the two shows, possibly manufactured and amplified by the rock press, no doubt makes a good story.

Another take is that both shows were completely different, and any supposed comparison was simply based on the fact that it was a rock/pop music series. In his memoir, Andy Kershaw noted the differences between the series were deeper still…

…(we) felt it was also our job to set the agenda rather than to be spoon-fed by the major labels and to jump into bed with them routinely and uncritically. If we felt a big label’s new priority band was lousy and there was no journalistic justification for having them on the show, they’d be directed instead to Newcastle.

Andy Kershaw (No Off Switch)

A good example of the ‘Old Grey’, and the ‘All New’ can be found in the edition broadcast on 15th March 1985. As was often the case, two bands were booked to perform live in the studio.

Opening the show (presumably a late replacement for the listed Faith Brothers) was ex-Scorpion Uli Jon Roth & his ‘Electric Sun’ band – as potent a mix of retro hard rock and psychedelia as it was possible to book at the time, a point noted in Andy Kershaw’s opening link:

KERSHAW: Is he a cosmic anachronism or the next big thing?

The subsequent interview also appeared to recognise a conflict between the show’s reputation and its ability to be a broad church.

KERSHAW: Are you frightened that in 1985, are you not worried that the kind of music that you play might be construed to being old-fashioned?

Mind you, there is something very likeable about Roth, who, when pushed by an incredulous Kershaw, gets the final word.

KERSHAW: Are you inspired by the cosmos, is it fair to say that?

ROTH: We all are.

KERSHAW: We all are? Even me?

ROTH: (laughing) Even you.

KERSHAW: Even though I don’t know about it?

ROTH: (Menacingly) Maybe you know more than you think?

The polar opposite to Electric Sun music (and indeed Kershaw’s visible excitement) was the booking of ‘The Jesus and Mary Chain’. Kershaw used their appearance to hit back against the critics of the show.

KERSHAW: How do you link a video of a nice lad like that with the first live TV performance of a group that have been hailed as the most controversial band since the Sex Pistols? Well, perhaps those critics of this programme who say it’s still old and very grey could offer some idea? I suspect that actually, they couldn’t. So, all I’m going to say is sit back, hold tight, and enjoy the total noise and summer sounds of the band that can’t get a gig anywhere, except on this programme. These are The Jesus and Mary Chain!

Indeed, it was a coup to get the band on Whistle Test, and important too, in the efforts to portray the programme as being up to date. Not that any of the band will have noticed.

I remember I was very, very drunk but most things you’re going to ask about I was absolutely pissed all the time. They got us down there at some ludicrous hour, like six in the morning, because they’d heard we were going to be hard to handle. We arrived from some party, having not been to bed, with a big stack of beers. They went, “Oh Christ!” but that was it. We were wobbling all over the place, generally being naughty boys.

Jim Reid (The Jesus and Mary Chain)

I think the idea was to get the band there early so they wouldn’t be wasted but when the band turned up, they were completely wasted. Yeah, so I don’t remember much. I just remember watching it when it was broadcast and being very excited by it.

Bobby Gillespie (The Jesus and Mary Chain)

We’d been up all night and it was just weird watching ourselves on telly later that night. We were all sat around this little fire with massive hangovers!”

Douglas Hart (The Jesus and Mary Chain)

It makes a good story that The Jesus and Mary Chain were in the studio at 6am. The reality is it probably just felt like 6am when they woke up (if indeed they did). The juggernaut that is the television production studio factory meant that the regular Whistle Test production schedule would accommodate some late morning recording.

Somehow, The Jesus and Mary Chain avoided setting the BBC switchboard buzzing. The complaints were saved for a folk festival in idyllic Cambridge.

We did a film about the Cambridge rock band competition which is unique in Britain because it was funded by the local council. We went and filmed the final where the winner was a band called Colonel Gomez. As part of this lead singer’s act he used to open his flies, and he had this huge great pink balloon which would blow up. So we had this huge balloon nob that would come up.

We put it out and there were complaints. This actually did cause a question in the House of Commons. If you have a look through Hansard there is somebody, I can’t remember who, who said “Will the minister condemn the disgusting, lascivious, blah blah, The Old Grey Whistle Test… ridiculous.”

I got a stinky note from the controller.

Trevor Dann

ELLEN: (To camera) Look I paid my TV license. We should not have filth like this flung at our pop kids. It’s a disgrace. It’s a family programme. Apologies, it won’t happen again.

Alongside the filth and the fury, Whistle Test was able to find the niche or ‘minority interests’, and to emphasise them in the spirit of public service broadcasting. For example, political and social themes were often highlighted. There were extended features on everything from the trials of support acts to the (lack of) infrastructure surrounding the Irish rock scene.

A notable example where the show featured something far removed from mass commercialism was in November 1984, where a large percentage of the show was devoted to the mid-1980s Jazz revival, featuring a reportage from the WAG club, to a live session from Working Week.

The range of themes offered played to the musical strengths of Whistle Test, perfectly suited the magazine format, provided a subtle distinction from the competition, and arguably demonstrated the strength of the two-producer production set-up.

Trevor and I had very different backgrounds as producers, so this could have meant very different shows with the weekly turnaround.

I don’t think this was an obvious problem in the flow of the series as a whole, thanks to the agreed weekly magazine structure of live bands, interviews, video vote, charts, etc.

John Burrowes

And visually, the series was a step up, with more dramatic lighting, a handheld camera, and liberal use of dry ice. In the case of The Sisters of Mercy, almost too much.

Not knowing that they would have been taking on an early evening timeslot, Dann and Burrowes must have been relieved by the positive audience and critical reception of the new Whistle Test. Music Week in 1985 noted how Whistle Test was central to the UK’s appreciation of America’s new traditionalist bands. When juxtaposed with the inclusion of bands such as Everything but the Girl, Microdisney, or the Penguin Cafe Orchestra, alongside the reaction to Jesus and Mary Chain, or The Sisters of Mercy, it’s clear that Whistle Test remained eclectic, could take risks, champion new blood, and capture exclusives.

However, in February 1985, something happened that, I would argue, was a direct reason for the ultimate demise of Whistle Test. A kick in the teeth, to which all future decisions and analyses about its longevity can be traced back to.

In 1984, Michael Grade became the controller of BBC1. His impact on the channel was considerable, clearing out a number of established formats, including Crackerjack (…”CRACKERJACK!”) and Doctor Who – although that series famously earned a reprieve of sorts. Pebble Mill at One was described as a “cuddly old jumper” meaning it was on borrowed time.

Recently commissioned programming was also affected – Blackadder required changes in its format to secure its continuation, while The Tripods – a high-budget adaptation of the novels of John Christopher – was cancelled before it had reached a natural conclusion. It cost too much.

Heavily trailed, and part of BBC1’s much anticipated weekday evening new lineup, the revamped chat show Wogan went live on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, from OGWT’s old stomping ground – the BBC television theatre in Shepherd’s Bush. Meanwhile, the BBC’s first new soap opera in aeons – EastEnders – was scheduled to clash with ITV’s Emmerdale Farm, on a Tuesday and Thursday, starting on the 19th February 1985.

And that meant a 7.00pm time slot.

It was nonsense really. When we were moved initially to 7:30pm, we got big audiences – something like two-three million and we used to say “Well, we’ve we’ve sorted this.”

Then BBC1 announced that they were launching a new soap opera called EastEnders exactly against it. So we were finished by then.

Trevor Dann

Presumably responding to the interest in the new soap opera, the BBC2 schedulers moved Whistle Test to half an hour earlier, also starting at 7.00pm. It’s hard to see the logic for the move, as Whistle Test would still be head-to-head. Perhaps, there was a worry that, given the Whistle Test magazine format, viewers might delay switching to BBC 1 if there was an item of interest to stick around for.

Given the high stakes in the new BBC1 lineup, it is unlikely that anything new would have been scheduled that could have had a detrimental impact on the BBC1 ratings. While EastEnders responded to the death of Reg Cox, Whistle Test had The Kane Gang and ex-New York Dolls leader David Johannson in the studio.

Soap opera, or a show with a specialised audience? 13 million people tuned into EastEnders.

Nonetheless, there was an encouraging outcome of the early success of the 1984-85 series – an extension to the series. Initially slated to run for five months, taking it to March 1985, Whistle Test continued further into the year. NME later stated that it was extended again after that, running until mid-June. Whatever the reality, the new live Whistle Test, ran for pretty much the same length of time – almost three-quarters of the year that OGWT used to run back in the 1970s. It would appear that the new format had proved a winner.

Even the music press seemed satisfied – just about. The NME ran an article on 25th May 1985, towards the conclusion of the series. Entitled ‘Old, Grey, us??’ The feature headlined a show on the up, and “leaving its dreary past behind.” It included interviews with Andy Kershaw and Trevor Dann. While it maintained the tradition of referencing The Tube in the same breath, it even went as far as to describe the Whistle Test revamp as young and ungrey. It lauded the consistent success of the live studio performances while highlighting the challenge of appealing to a new young audience while retaining the 30+ somethings. In the light of a later 1987 article, that will be presented to the court in part five of this retrospective, this one felt like peace had been declared.

It’s hard to define a ‘good’ series of Whistle Test. It’s largely subjective and dependent on your taste in music. But as noted in Doctor Who in 2013, we are more than capable of revisiting the “old favourites.”

In terms of analysing the content and production of a television series, the 1984 – 85 revamp might just be the best series of Whistle Test over its 16-year history. The sound was suitably mid-1980s – often with a healthy dollop of reverberation, and didn’t lose its quality. The visual presentation was confident, the broad mix of pre-recorded features and live elements, such as the charts and video votes, were balanced, and crucially, the choice of music remained eclectic, but didn’t lose sight of the series’ long-standing and broad-church audiences.

The show might have changed its name during the previous series, but the move to a live format was the big reinvention. While ‘all-new’ it remained distinct from The Tube, by cultivating the ‘magazine’ format that had been a part of the show for many years.

It really was a big revamp – no half-measures. And looking back, I’m struck by how comprehensive the change was.

This chapter has focused on the importance of presentation and the construction of an appealing format. It’s easy to see how OGWT evolved from an earnest mix of music and interviews to the magazine format of the mid-1980s, supplemented by filmed investigations into a particular aspect of the music scene, promo videos galore, video votes, archive material, chart rundowns, reviews, and competitions.

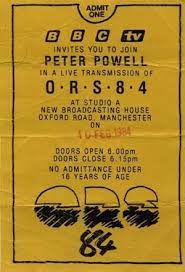

A reminder of the stakes involved in successfully revamping a show was laid bare when, in March 1985, fellow BBC2 show The Oxford Road Show (1981-85) finally ended its run. Following on from Something Else (1978-82), the show was recorded at the BBC’s Manchester studio on – yes, you guessed it – Oxford Road.

Sometimes mocked for its presentational style, the show never settled in terms of presentation and presenters. In 1984, it was revamped. The “live and lucid look at the week” shifted in tone, with an increase in celebrity guests and Radio 1 DJs. The show became “TV’s electronic magazine”.

In a similar mode to the name change that followed Whistle Test, the previous label was seen as passé, so Oxford Road Show morphed into the contemporary tag ORS 84. The following year, ORS 85 was hosted by a revolving door of hosts, usually accompanied by Timmy Mallet. A quick glance at one episode, featuring Roman Holliday, owed more to Pebble Mill at One in its use of singers walking down corridors within the broadcasting centre, before arriving in the studio – charming in its way, but not quite the young people that the show was aimed at.

Having moved away from its own little corner of late-night existence, Whistle Test was never more visible, both in terms of scheduling and profile. Indeed, a few weeks after the final edition of the 1984-85 season, the Whistle Test unit would be performing on the world stage.

Next Time – The perils of studio and Outside Broadcasts! No Longer Old, No Longer Grey – Part Four.

References and acknowledgements at the end of the final chapter.

Leave a comment